Last episode here, we saw the engineering contingent in the Reclamation Service ‘breaking loose’ from the science-driven US Geological Survey, becoming the Bureau of Reclamation in 1907; Reclamation’s engineers were no longer constrained to the smaller local projects envisioned in the 1902 Reclamation Act, but were free to take on larger, regional projects like the Theodore Roosevelt Dam or the Gunnison Tunnel described in the last post.

But before the Bureau of Reclamation could really launch into controlling and developing the Colorado River mainstem, there was another, less visible ‘political infrastructure’ that had to be constructed, around the dynamic water law that had evolved in the seven states whose destiny depended on the Colorado River. A basin-wide interstate issue about water rights had to be worked out. Time now to take a look at the water law foundational to the development of the arid West.

Western water law begins with a simple premise: first come, first served. This is the basis of the ‘Appropriations Doctrine’ for water: the rights to use the waters of a stream are ranked by seniority of appropriation; even if you are ‘upstream with a shovel,’ you have to let enough water go by to meet the claims of downstream appropriators senior to you.

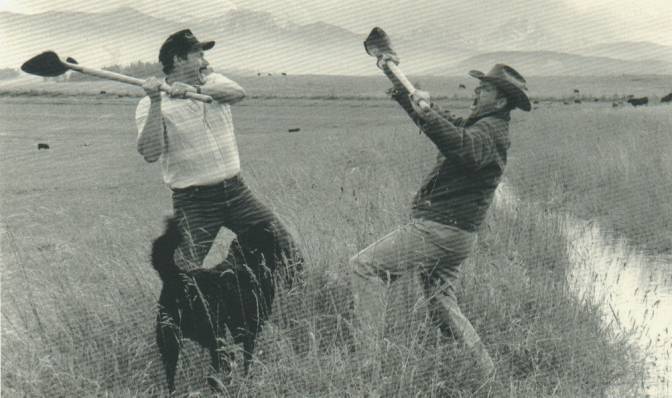

This process began in the mining camps of the California gold rush, and continued as farmers came to feed and fuel the mining camps, and spread on as gold fever spread. It is important to note that this law was not already in place when the miners arrived at the site of a gold or silver strike, with everyone docilely obeying it. It was true ‘common law’ that evolved out of numerous encounters where individuals stood up for their senior right with fists, shovels or firearms, trial by combat, the results were considered cosmic justice even if the wronged person was dead. But eventually, the camp itself would begin enforcing that evolving law once it became organized as a community with a marshal and justice of the peace.

From that basic premise of ‘first come, first served,’ however, western water law evolved early on as one of the more overt expressions of the ‘Two Americas’ tension between the Industrial Revolution and the Agrarian Counterrevolution (see April 4 post). In both the mining camps and the farm communities, early settlers and unsettlers alike were aware of the voracious nature of the Industrial Revolution and the vast wealth that drove it. They were concerned that the big money would come in and tie up all the water, leasing it out to farmers and ranchers on their own terms since, without the water, the homesteaded land was essentially worthless.

So from the start under the evolving law, the water was declared to be the property of all the people, subject to appropriation – but the individuals or ditch companies would not own the water they appropriated, just the right to use it (a usufruct right). And – most important – they could only appropriate the amount of water they could put directly to use. This element in the evolving water law was intended to keep speculators out and make the virtually free homestead land and essential water available to the maximum number of farmers.

Another important element in the evolving water law was implicit in the statement in Colorado’s constitution that ‘the right to divert shall never be denied,’ even if one’s land was not adjacent to a flowing stream or body of water. If all the riparian land in a valley were taken up, subsequent irrigators ‘inland’ had the right to run their access ditch to the stream across a riparian owner’s land, with an easement payment set by the county commissioners. This ruled out control of the whole water supply by riparian water users.

All of this was enshrined in Colorado’s constitution, and those of other western states with mostly minor variations; the written law smoothed out some of the ambiguities of local enforcement – or as sometimes happens when lawyers write, enhanced the ambiguities.

One major variation among the states, however, was in the granting of the water rights. In Wyoming and some other western states this duty was given to the office of the State Engineer. The state engineer issued all rights to use the water, on advisement by division engineers for major watersheds and commissioners of local streams. The water commissioner was usually one of the local farmers – or sometimes a farmer’s wife – so administration at that level was less a matter of laying down the law than a matter of people skills for working things out between a couple farmers at a headgate with sharpened shovels. Disputes that couldn’t be worked out locally went to the division engineer and ultimately to the state engineer whose word was usually final, although appeals could be made to the courts.

In Colorado, however, while the same system of state and division engineers existed to record and administer water rights, all water rights were issued through the state’s district courts, which were mostly laid out with major watershed boundaries. The District Judge was also the Water Court Judge, in charge of adjudicating appropriated rights, although he could appoint a ‘water referee’ to collect information and advise him in disputes.

Leaving it to the courts had the disadvantage of encouraging a protagonistic aspect to the administration of water law. Anyone could file a statement of opposition to anyone else’s claim of a water right, and be heard in water court. And because adjudications of appropriations only happened when the judge could do several at a time, there were always two dates associated with a water right: the date of adjudication, which was a matter of official record; and an earlier appropriation date, which was the appropriator’s own record or recollection of when work began on the appropriation in question. This appropriation could be disputed by another irrigator who remembered something else and had filed on some of the same water.

The court system for all water rights administration also enabled situations where a party with an eloquent lawyer could expand the evolving law with a well-argued case ‘outside the box.’ This began to happen in ways that undermined the agrarian roots of water law. In his ‘Report on the Lands of the Arid Region,’ John Wesley Powell – who perhaps took the idea of the Agrarian Counterrevolution more seriously than many of the farmers who benefitted from the land and water law designed to promote it – had emphasized that it was important for the right to use water to be legally tied to the land it irrigated. But somehow that principle was abandoned (or never really embraced), and the right to use water became a ‘property right’ independent of the land the use of water had been acquired for. A water right – the rather abstract right to use water from a stream – could be bought and sold like a separate piece of real estate, and the water used consumptively under that right could be moved to wherever the new owner wished. This opened a back door for money into the appropriations doctrine: what had been appropriated free from the commons acquired a price, once put to use, and was no longer a pure usufructory right.

Another issue initially involving a couple of modest creeks on Colorado’s Front Range became a much bigger deal in the development of the state. In the 1860s settlers on Left Hand Creek, a tributary in the Boulder Creek Basin, initiated a high-elevation diversion from a tributary in the adjacent South St. Vrain Basin. In 1879 settlers in the St. Vrain Basin objected to this out-of-basin diversion, and, led by farmer Rubin Coffin, tore out the Left Hand Company’s diversion dam, letting the water flow again in the South St. Vrain watershed.

The Left Hand Ditch Company sued Coffin and the other St. Vrain irrigators for damages. This was three years after Colorado became a state, and the water law sketched out in the state constitution had not really been tested. A jury trial was finally held in 1881, and the jury found for the Left Hand company due to the priority of its appropriation for use.

Because this was a diversion out of one watershed into another watershed, transbasin diversions became acceptable under water law, even though such a diversion represented a hundred-percent loss of water use for the basin of origin with no obligation accrued to the transbasin diverter. This was not a big deal in Left Hand v. Coffin, since both streams ended up in the St. Vrain River downstream. But it became a considerably bigger deal in the 1930s when two much larger transbasin diversions were initiated from the West Slope to the East Slope: the Twin Lakes Tunnel from the Roaring Fork headwaters to the Arkansas Basin and its sugar beet fields, and the Moffat Tunnel Pilot Bore diversion from the Fraser River headwaters to the Denver area. These were significant losses of water for the West Slope, with no mitigation from the basin of destination.

The Denver Board of Water Commissioners added insult to injury – or maybe just injury to injury – when it filed on water rights for its Moffat Tunnel diversion in 1937. They filed for roughly twice the amount of water they could actually put to use in the 1930s; this was a direct assault on the anti-speculation clause in the evolving body of water law, which said no claim could be made for more water than the appropriator could directly put to use. But Denver’s principal water attorney, Glenn Saunders, argued that a ‘great and growing city’ needed to plan its water supply well in advance of its immediate needs. The rural West Slope district judge disagreed and granted Denver only half of its claim. But the case was appealed to the Colorado Supreme Court, and it agreed with the Denver Water Board, finding that ‘it is not speculation but the highest prudence on the part of the city to obtain appropriations of water that will satisfy the needs resulting from a normal increase in population within a reasonable period of time.’

That appeared to breach the anti-speculation clause, at least for cities, and launched an ongoing conflict between the West Slope and the Denver Water Board that persisted until the 1990s. The state supreme court has been called upon several times – most recently in 2008 – to further refine what constitutes ‘a normal increase in population within a reasonable period of time,’ in an attempt to pin down the distinction between urban ‘prudence’ and ‘speculation.’

When the Bureau of Reclamation got into the West-Slope-to-East transbasin diversion game with the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, also in the 1930s, it set an example of ‘compensatory storage’ for the West Slope, paid for by the East Slope diverters, to mitigate for the loss of a valuable resource. But the Denver Water Board continued to take what it wanted with no thought to the West Slope’s needs, until a major shutdown of a project around 1990 caused it to re-evaluate its history and future – but that’s a story for another time.

For now – suffice it to note that in the broad sweep of American history, the unstoppable force of the Industrial Revolution was again carving inroads into a system originally set up, by the farmers, to favor the Agrarian Counterrevolution.

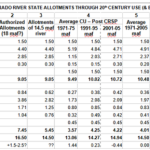

On the other hand, however, the farmers and ranchers of Colorado got there first and today still own the rights to 85 percent of the water in Colorado, with less than 10 percent for municipal and industrial use. In the entire Colorado River region 70 percent of the water still goes to agriculture – although much of that in the lower region is large-scale agribusiness that no longer resembles Jefferson’s agrarian vision of yeoman farmers in a decentralized grassroots democracy. The idea that the cities could ‘steal’ all the ag water and ‘kill’ agriculture is kind of silly, however; if the cities doubled the amount they use now, and bought it all from agricultural users, it would only reduce ag’s share by 10-20 percent – hardly a death blow.

There are two notable facts about the appropriations doctrine to consider today. One is the fact that there is no water left to appropriate; it is all developed, but in a dynamic environment of growth and change which the appropriations doctrine nurtured but can no longer effectively manage. The second fact is as stated by the late lamented Greg Hobbs, retired Colorado Supreme Court Justice: ‘We are no longer developing the resource; we are learning how to share the developed resource.’ This may require a difficult transition to a new, barely imaginable distribution system for the water resource that will have to be both just and fair to the agrarian past as well as to the emergent urban and industrial future. Not easy.

Next time – what happens when the seven Colorado River Basin states realize they all have to acknowledge each other’s prior appropriations – with California almost lapping the pack….

Hi George,

Great essay.

I have one question. I wonder if the project you referred to that changed the Denver Water Board’s access to any West Slope water it wanted was the Two Forks Dam?

Maybe not since it was proposed on the S. Platte River.

Paula Kauffman

Yes – It was the EPA’s rejection of Two Forks that caused the ‘Denver Water Board’ to go silent for a couple years, then re-emerge as a kinder, gentler ‘Denver Water.’ They had wanted West Slope water for the Two Forks Dam. The ‘Roundtable’ that they worked through to get state approval for Two Forks had recommended that, instead, they should maybe expand Gross Reservoir, to bring over more of the Fraser River water they already have conditional rights for. That’s what they are trying to do now, but not finding that easy either…. We’ll look at that one of these days – the crazy story of a transmountain diversion proposal that the West Slope basin of origin likes, but the East Slope basin of destination doesn’t like….

Really enjoyed your synopsis of Colorado Water Law. It seems to me that the antiquated appropriations agreements of yesterday year needs to be “Re-negotiated and Re-appropriated”.

The battle over the “Union Park” diversion — is it truly over with and a dead issue?

Thanks, George. Before reading your history of the Colorado river and its use, I had no clue…

Sandy Bush