…the fabled Hassayampa… of whose waters, if any drink,

they can no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance.– Mary Austin, ‘Land of Little Rain’

That fabled Hassayampa is in the news these days, down in Arizona. The Hassayampa River does exist, by the way: an intermittent stream that flows off the south slopes of the Colorado Plateau, and down through a desert valley west of the sprawling phenomenon of Phoenix, where it joins the Gila River, which in turn joins the Colorado River down near Yuma and the Mexican border.

A new development has been proposed for the lower Hassayampa Valley, catering to those trying to stay out ahead of the sprawl: the Howard Hughes Corporation wants to turn 37,000 acres of Sonoran desert land there, just west of the White Tank Mountains, into a new development, Teravalis, with 100,000 homes for maybe 300,000 people, and 55 million square feet of commercial space. According to a story in the New York Times, ‘Teravalis is seen by local and state leaders as a crowning achievement in a booming real estate market.’

Truly someone has been drinking from the fabled Hassayampa. Teravalis, in fact, plans to tap an aquifer under the Hassayampa Basin for a water supply for this massive development; they will all be drinking from the Hassayampa. Some Arizonans have, however, looked at the naked facts about water supplies in the desert, and the Phoenix area has a law in effect stating that every development has to show evidence that it has a 100-year water supply, and can replace groundwater it consumes. This law was mandated back in 1980 by the Interior Department, as a condition for funding and constructing the Central Arizona Project that brings water 300 miles from the Colorado River to the Phoenix-Tucson corridor. (The law, it should be noted, only applies to urban ‘Active Management Areas,’ and does not apply to the non-urban parts of the state where agriculture consumes a much larger share of the state’s water.)

Teravalis is on hold for now, under that law, until a believable estimate is made of how much water the Hassayampa aquifer actually contains. But – this is only one of several new developments proposed for the Phoenix area alone; remember that Arizona is one of the seven Colorado River states that have been told by the Interior Department that they must collectively cut their water consumption by maybe as much as a third, to prevent a collapse of the region’s water supply system, centered on storage in Mead and Powell Reservoirs.

Yet the Teravalis story is replicated in all seven of those states to some extent; each state has at least one metropolitan area that continues to spread like a cowflop on a flat rock, ever outward into dry lands. We have one right here in the little City of Gunnison where I live, spreading out into our pastureland, that is just completing its infrastructure of pipes and wires. We are a very small ‘city’ of five or six thousand that will never be considered a metropolis or even a micropolis (he bravely projects, back here in 2023), but when our ‘Teravalis’ is built out, mid-century, our current population will have increased by 30 percent, plus or minus.

We seem to be oriented to grow even when we sense that it might be unwise. American historian Richard White commented on this in his history of the West, It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own. Parsing what he saw as the post-World War II ‘rise of the metropolitan West,’ he credited it mostly to a cycle of planning based on growth, created by ‘what scholars have called growth networks – that is, alliances of bankers, corporate executives, real estate interests, politicians, and labor leaders… [which] gained popular support by arguing that growth equals prosperity.’ We are, in short, culturally and economically organized for growth; it is who and what we are: the growth network creates new jobs for newcomers in the growth industries, building Tervalises for another wave of newcomers who will be employed by the growth industries in building ever newer Teravalises for et cetera et cetera….

Most of the West’s SMAs (Statistical Metropolitan Areas) today boast about the fact that, despite major increases in population, they are actually distributing about the same amount of water they were distributing around 1970. This means that people are using significantly less per capita than they were around 1970 – which is to say: they are conserving water, or using what they use in more efficient fixtures, or both. But this does not necessarily improve their situation. It just ensures enough water for more people to move to their SMA, which (even with sprawl) increases the general density of humanity in the SMA, which causes more traffic congestion, more people in the parks and pools, more queues for restaurants and DMVs, and generally a diminishing quality of life. Conservation loses some of the romantic radiance of civic virtue when the citizen realizes conservation functions mostly to make things available for ever more people.

The development plans do get better and more resource conscious – more ‘watersmart,’ to use a popular buzzword. But they are still intended to fill up with new people who will be using a water resource that we now know is not just limited, but is diminishing. Five or six percent more of it just disappears back to the atmosphere with every degree we increase the ambient temperature – a relentless process of increase that will be facilitated by our development here in the Upper Gunnison, as well as Phoenix’s and everyone else’s. This is not just the usual dire and depressing predictions by scientists; it is what we are already seeing in the diminishing Colorado River water supply – down 20 percent over the last 40 years (faster even than predicted by prescient scientists).

One wants to ask, about that ‘naked fact’ cited in scores of articles about the river just this year: why are there 40 million of us are living in the driest parts of the continent, with more of us coming all the time to fill up these developments? The short answer to that question: we have become a swarming species on the planet – the biologist’s descriptor for a species over which natural ecosystemic processes have lost control. We have been, over the past 10,000 years, a remarkably adaptive species, able to fit into practically every land-based environment, and we have become the dominant species in all of those environments, thriving and increasing at the expense of most of their other animal and plant inhabitants. The deserts are not the only place where there are so many of us; nearly everywhere we go – there we are, lots of us, and more coming all the time.

Through the romantic prisms of what we call civilization, we have been a remarkable success, and all indications are that we plan to become even more successful. It is clear that there is no public will for trying to rein in the swarm, to put limits on our population expansion. When nature tries to control us, bring us back into some degree of balance with the rest of creation, we declare open war on nature and its controls – no COVID or cancer will have its way with us! We fight on all fronts for a world in which people do not die of diseases or malfunctioning parts, a world in which no children die before they are grown, in which everyone can live to be 100, 110, 140, or maybe someday forever.

In other words, we demonstrate through our works and our wars, that we are not going to limit or control ourselves – the first species with the capacity to successfully challenge the often harsh natural systems that restore balance in species swarms. Therefore – so it seems to me – we give ourselves no choice but to make the planet ever more human-centered, to direct ever more of its resources and systems to the meeting of our ever-expanding needs and wants. To put this another way – we can applaud ourselves for quickly finding a vaccine for the COVID virus nature threw at us, but we have to put that in the context of our very active participation in the greatest species die-off since an asteroid took out the dinosaurs and much of the rest of nature’s life project millions of years ago. Is there any other alternative way of seeing what’s going on? Am I missing something?

That is where we find ourselves today, at any rate, in the Colorado River region: confronting the challenge of fitting a finite and even diminishing essential resource to an apparently unlimited demand. ‘Teravalis is seen by local and state leaders as a crowning achievement in a booming real estate market.’ It’s Teravalises all the way down – down, in that particular case, to an unquantified aquifer related to an intermittent desert stream from whose fabulous waters all humankind seems to want to drink. Does anyone really doubt, at this point, that the Hassayampa aquifer, or that aquifer combined with a pipe from some other aquifer, or some even more complex plumbing arrangement, will be proven to be sufficient to provide Teravalis with the radiant vision of a 100-year water supply? It’s the economy, stupid.

As I write here, we are tracking toward a February deadline set by the Interior Department/Bureau of Reclamation, mandating that the ‘seven city-states of Cibola’ come up with massive cuts in the consumptive use of the Colorado River’s waters – at least two million acre-feet, maybe up to four, in order to ‘save’ the river’s storage and distribution system. If the states fail at this (as they did with an earlier Interior deadline), then the Interior Department will make the cuts for them (as they threatened or promised, but didn’t do, when the states failed to meet that earlier deadline). This time, presumably, they really mean it.

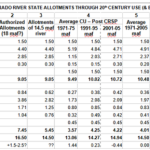

This time, the state with the smallest share of the river, Nevada, has drafted up a plan that the other states have agreed is at least a reasonable way to start discussions. If it can be hammered with its current numbers into something acceptable to all the states, even California, it would reduce consumptive use this coming year by around 2.5 million acre-feet. Most of it would come out of the Lower River Basin’s water budget, and would include things like finally acknowledging that their share of the river includes responsibility for the evaporation from their reservoirs and fields. The Upper River Basin would be contributing maybe half a million acre-feet, since its usage quantification already reflects its evaporation plus most of the depletions to date from climate change. (The Upper River Basin produces 80-90 percent of the river’s entire flow.)

The goal, according to Nevada officials, is to share the pain across the entire system. That seems like a reasonable goal – except that it is at odds with the most sacred cow in western water use, the appropriations doctrine, which says that junior appropriators should bear the pain before any senior users are asked to. A ‘naked fact’ that California – holder of the largest senior appropriations on the river – has already been asserting. But as John Entsminger, General Manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, has said, ‘If 27 million Americans don’t have water, then those laws will not be followed.’

But… again: what are 27 million, or 40 million, or by mid-century 60 million people doing, demanding water from a modest and diminishing river in the desert lands of the Southwest? I ask myself, being one of them. And can only think to say: Welcome to the Anthropocene. Still all radiant with the color of romance, which lets us still think that a water supply problem is somehow a problem with the water supply…. The second century of the Anthropocene awaits the woke. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile – a belated wish, to all of you who have read this far, for a good year coming: a year filled with wondrous things, like a union between our naked facts and the radiant color of romance that would not be merely cultureporn; a year filled with interesting things that are not merely the fulfillment of a Chinese curse; a year in which we learn to distinguish between a river in trouble and a civilization in trouble.

To a good year:)

Great read George

It has been only 55 years since you sat on the banks of Crystal Creek listening to the elk bugle along the hillsides of Black Mesa, a small trickle of water still flowing in the creek in late summer. I’ll bet there are days when those bugles are still beckoning you to come back to that place.

Excellent piece, George. “Conservation. . . functions mostly to make things available for ever more people.” So simple; yet I blush to admit I never thought of it like that. That slapping sound you hear is my palm making contact with my forehead.

Remember when Dick Cheney dismissed conservation as nothing but a show of ‘personal virtue’ – a statement I found really offensive (and still do somewhat). But it has an element of truth; as with all things, conservation deserves to be sorted through to see whether it’s going to really improve anything.

Climate change in general and desert water management in specific may be something we just can’t get our heads around.

Habits won’t change until they simply have to.

Planning that far ahead might be beyond our collective grasp?

Especially when others will bear more of the burden… I think it’s called an Externality.

The benefits are privatized and the costs are socialized.

Climate change is seen by some as misplaced incentives.

Hi George,

I started reading this when you first sent it out but somehow got sidetracked, and as I finish it now, I feel defeated. Your writing is so beautiful while the message is scary and sad, not only for our dear, dear Colorado River, but for the negative repercussions of the Anthropocene period on the entire planet.

I didn’t know about the Nevada proposal you referred to. Good; something’s on the table.

I assume you subscribe to the Denver Post and saw last Sunday’s coverage taking up the entire front section. The bottom line–agriculture consumes over 70 the usage–so start there.

Thanks, as always,

Paula Kauffman

I really enjoyed the article, George. However, even if mandates come out of the Federal Government, whatever they may be, the enforcement phase of those mandates is the big question mark in my mind. The government can’t even enforce the EXISTING laws to control our southern border. I still believe that “de-salinization of Pacific Ocean waters is part of the solution.

Desalinization probably is part of the solution, but it is expensive – just getting ocean water to a potable level is expensive, but probably not as expensive as then getting the water from the oceanside to where it is needed…. Arizona is considering it, possibly working with other Lower River states on a big plant in Mexico. If they could create a million-acre-foot plant there, they could trade that water for a million acre-feet of the current Mexican Colorado River apportionment that could then be distributed to those states.