‘Caliphobia’ is a cultural germ that infects many Americans everywhere. ‘Caliphobia’ is fear and loathing of the State of California, the state that always seems to be ahead of everyone else in everything, bringing us everything from new entertainments and toys, to new laws on cultural frontiers the rest of us know we ought to be brave enough to embrace ourselves. I’m thinking of things like auto emission standards where the size of the California market brought the automobile industry to heel, with the nation eventually falling in line too. We hate them when they’re right.

Californians also occasionally take a big step backward in a deliberate way, and the nation eventually falls in step there too – remember ‘Proposition 13,’ California’s 1978 property tax revolution to protect existing homeowners at the expense of community health, a battle which ultimately generated the national ‘Tea Party’ and the Trumpian ‘I’ve got mine Jack’ culture. We hate them when they’re successfully wrong.

California always seems to be first with the worst as well as the best. For this they are generally disliked, even hated, in a subrational way that is often tinged with envy – Caliphobia. This leads to things like bumper stickers saying ‘Don’t Californicate us!’ and the perception of Californians as emigrants from the gridlock of their success, spreading through the West with fistfuls of money to drive up our housing prices.

California’s impact nationally has to do mostly with its size and population. Close to one of every eight Americans lives in California – approaching 40 million. One-eighth of our Congresspeople are part of the 53-person California delegation.

But where California – and Caliphobia – has had its largest and most ingrained impact may be in the Colorado River Region – the seven states through or between which the Colorado River meanders. California has close to twice as many people and Congressmen as the other six states combined.

We see Caliphobia rearing its head today on the Colorado, as six of the seven Basin states have put forward a plan for major cuts in water use in the Basin – cuts the Interior Department says are essential if their system of storage and distribution structures are going to remain functional. But California refuses to sign onto that plan, in which they would take a big hit; instead, they have put forward their own plan in which they would take a moderate hit, but only after Arizona and Nevada have taken big hits, demanding that their large senior priority rights be honored. This is engendering media headlines like ‘California Isn’t Playing Nice on the Colorado River’ or ‘Unlike California, Vegas isn’t gambling with its future by squandering water.’

Caliphobia is nothing new along the Colorado River, however. It goes back to the early 20th century. All seven states in the Region – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming – had adopted the first come, first served appropriation doctrine for the distribution of the use of water. Appropriation law – free water for free land, permanently if you get there early – became a powerful growth engine that contributed to growth in all seven states in the early 20th century, but California’s population quintupled in that time.

This gave the six ‘slower’ states reason to fear that, in an unchecked seven-state horse race to appropriate use of the Colorado River’s water, California had the pole position and a fast start, and might put most of the river’s water to use while they were still getting started. The fact that the developers of the Salton Sink, aka the Imperial Valley, down at the end of the river, had a 1901 appropriation filing for more than two million acre-feet of river water lent substance to their fear. Caliphobia spread along the river.

Their Caliphobia led to the convening, in 1922, of the Colorado River Compact commission, with the original intention to make an equitable seven-way division of the use of the river that would override the appropriation doctrine at the interstate level, assuring each state of a share of the river to develop in its own good time. But a seven-way split proved impossible to attain; they lacked necessary information about how much water was even in the river, and the only information they had about their own futures came from their own overheated imaginations. So in something close to desperation, with time running out, they came up with a big sloppy broad stroke: dividing the river in two, an Upper Basin with the four states above the unsettled canyon region (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming), and a Lower Basin with the three states below the canyons (Arizona, California, and Nevada). Basically, each Basin would get the consumptive use of 7.5 million acre-feet (maf), to further divide among themselves as their futures unfolded.

It is hard to see the Compact as a real success – certainly not an achievement deserving the reverence most water mavens hold it in today. It gave the four Upper Basin states relief from having to compete for water with California, but it left Arizona and Nevada in the cage with California, and Arizona refused to ratify the Compact as a result. California officials said their state would not ratify the Compact until there was solid assurance that the storage dam would be built. All the Compact really achieved was a minimum show of agreement by six out of the seven states, which Congress found acceptable enough, and proceeded with the Boulder Canyon Project Act that finally passed in 1929.

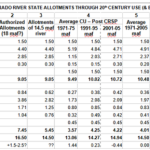

The Act itself relieved the Lower Basin states of the stress of dividing up their 7.5 maf – difficult given Arizona’s bad case of Caliphobia – by doing the division for them: 4.4 maf for California, 2.8 maf for Arizona, and 300,000 af for Nevada. Why so little for Nevada? All the action in Nevada then was in the western part of the state, in the relatively well-watered mining and ranching area just east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, four hundred miles from the Colorado River. The only town in southeastern Nevada was Las Vegas, a little flag-stop collection of ranchers and prospectors.

Caliphobia was enough of a presence in Congress so that, before the representatives would vote on the Boulder Canyon Project Act, California was required to pass a state law that the state would limit its use of Colorado River water to the 4.4 maf specified in the Act. California passed that law docilely enough in 1929; the Act contained not just the big dam to control the river, but the weir dam and All-American Canal for getting water to their Imperial Valley, so they had a lot to gain by complying.

But then, once the Act was passed and construction had begun, the seven largest California users got together in 1931 to divvy up their 4.4 maf – and an additional 962,000 acre-feet that they said the Upper Basin wouldn’t be using for decades, so why shouldn’t they use it in the meantime?

They were, in other words, going to use the Upper Basin’s unused share of the river to grow on, in hopes that there would prove to still be excess undivided water in the Basin when the Upper Basin needed its water – or that the engineers would have figured out how to bring new water in from some other river with water to spare. Early Anthropocene thinking: something would come along to keep them from being limited to their 4.4 maf. The intrastate Seven-party Agreement became part of the ‘Law of the River,’ along with the 1929 California Limitation Law.

The Metropolitan Water District, created to serve the Los Angeles-San Diego metropolitan area with Colorado River water, bet on the permanence of that surplus water in a big way: they built the 250-mile Colorado River Aqueduct to carry twice their share of the 4.4 legal allotment – a concrete conviction that they would not be limited.

The Bureau went along with this, given California’s assurance that it would only use ‘surplus water’ so long as it existed; it was consistent with the Bureau’s optimistic outlook for the future of the river’s flow – even though in 1931, the river’s flow dropped to half of the allotted 15 maf, the beginning of a droughty decade. The myth of a surplus flow, above and beyond the Compact allotments, was born, and would persist on paper too – well, to the present: it has been the increasingly fictitious surplus that supposedly ‘paid’ the 1.5 maf of evaporation and other system losses on the lower river.

The surplus was also supposed to take care of most of the Mexican allotment too, once that was negotiated in 1944. Anticipating an eventual allotment to Mexico, the Compact had said that ‘such waters shall be supplied first from the waters

which are surplus over and above the aggregate’ allotted to the states, and ‘if such surplus shall

prove insufficient for this purpose, then, the burden of such deficiency shall be equally borne’ by the two basins. More about that in a moment.

Caliphobia in the Upper Basin states increased as it became increasingly obvious after the 1930s drought that there was probably never going to be enough water in the river consistently for them to get a full 7.5 maf share. Yet the Compact committed them to ‘not cause the flow at Lee Ferry (the division point) to be depleted’ below 75 maf in any 10-year period. So even though there was not enough for their full allotment, they had to let the Lower Basin’s full allotment go downriver, or else – well, the Compact said nothing about what would or should happen if the flow at Lee Ferry fell below the Compact minimum, but that only enabled the Caliphobic imagination to run wild on what California would do to Upper Basin users in such an instance.

That clause could have been interpreted as a mere caution to make sure the Upper Basin users themselves were not responsible for a seriously diminished flow of the erratic river past Lee Ferry. But it could also be interpreted as a delivery commitment even if the diminished flows were caused by something other than human uses, like a two decade drought – which would already have seriously impacted the Upper Basin. Would the Lower Basin – California – add insult to injury by placing a call on them to further diminish their own uses to meet the 7.5 maf ‘obligation’? Letting the Lower Basin escape sharing any of the pain from the erratic river?

I find no evidence that California and Arizona ever officially threatened that, but the Caliphobic imagination believed it would happen, so the 1948 Upper Colorado River Compact in a sense codified it as a delivery obligation no matter what, and even included punishment in a ‘call’ situation, for Upper Basin states who might have had gone above their percentage of the river’s highly variable flows.

Why did the Upper Basin not take advantage instead of the Compact’s Article VI invitation, ‘should any claim or controversy arise between any two or more of the signatory States,’ to work out a more equitable modification to the Compact? Caliphobia: fear that California was so big and powerful that it would just roll right over the four states. The six Davids were basically too timid to take on their Goliath.

Another insult was added to the cumulative inequity to the Upper Basin in 1970 when, with Powell Reservoir filling behind Glen Canyon Dam, ‘Operating Criteria for Colorado System Reservoirs’ were developed that set a desired minimum release from Powell for the Lower Basin, not the 7.5 maf Compact allotment, but 8.23 maf, the Compact allotment plus half of the Mexican obligation, to be shared among the four states. But was the Lower Basin subtracting their half of the Mexican obligation from their allotments? No, they were still relying on ‘surplus’ flows, even though with ever increasing Upper Basin use, and the Central Arizona Project under construction, that surplus was steadily diminishing.

It wasn’t until 2003 that the Interior Department – perhaps also a little fearful of California – cleared its throat and told California that it was time to give up the use of a no longer existing surplus. To everyone’s surprise, California agreed that, yes, it probably was time, and the terms of the ‘California Quantification Settlement Agreement’ were worked out, and California is now back to 4.4 maf, sometimes even a little less.

Does this mean that the basic mythic story of the past century is no longer Goliath and the six Caliphobic Davids, but is more Gulliver getting tied down by the Caliphobic Lilliputians? How the current situation among the seven states shakes out will tell us more on that.

On the one hand, there are probably thousands of farmers on spreads of all sizes throughout the Basin quietly hoping that California’s stand for the primacy of appropriation law succeeds. The future of that body of law may hang in the balance. Too many people are asking questions like, how can we resolve anything with an appropriation law when everything is already appropriated? The farmers are probably happy to have one of the really big dogs making their case.

On the other hand, the six-state plan is not really an appropriation issue; it is primarily an effort to clean up an error left standing too long: the Lower Basin has no surplus left in the water bank to cover its system losses – or its Mexican obligation, for that matter. (Why has that not been mentioned yet?) The resulting ‘structural deficit’ is why Mead Reservoir outflow is exceeding available inflow, and the logical thing to do is the ‘Nevada solution’ of simply parceling out that deficit in some equitable way among the three states, reducing their allotments accordingly. There is not really a priority issue involved in the six-state plan.

However it all shakes out in the next several months, we might hope that the irrational aspects of Caliphobia might phase out, and no question about equity in the Basin be left unasked out of fear. There is not enough love for California anywhere, even on the national level, for it to get away with throwing its weight around.

I don’t have Califphobia, more of a broken heart. My earliest water work was in California and I was involved in many of the exciting things they were doing in the 80s.. It all seemed simpler than in Colorado. Turns out it was smoke and mirrors. Once the innovators were dead and gone, things went back to usual with no significant progress scientifically, structurally or legally. In fact the legal realm is a good 50 to hundred years behind Colorado on groundwater and probably on other things.. Some of the greatest water minds in the world still live in California and are virtually ignored, like World Water winner Tak Asano and his colleagues at UC Davis. So I am angry with California in part because I feel deceived and betrayed. Turns out it always comes down to providing for the richest interests, always.

Sadly, Caliphobia affects the good as well as the bad. I remember the heavy London like smog that would be gone if fossil fuels were under even better control But far too many states vilify that progress as they do the many truly humane social services that, have sadly suffered in recent years but are still miles better than anywhere else. WE should learn and build upon the lessons of California and make our own homes better for everyone.

Thanks for the perspective, Lori. I need to consult with you on what California was doing in the 80s…. And I do agree: Caliphobia (the envy aspect) gets in the way of appreciating and more quickly adopting the progressive things that come from there.

Hi George,

I learned a lot and enjoyed as always, especially your “Gulliver’s Travels” images. Let’s hope your prediction holds true.

Best, Paula

What a tangled web!

The whole thing is beyond bizarre, wrong and depressing. But they will never learn the real hard truth of the matter by themselves.

ken

I keep pointing out Arizona takes as much water out of the Colorado River System as California, more counting groundwater, and journos keep saying California is taking all the water.

The late Herb Guenther, who used worked for AZ’s ADWR 2003-2001 and threatened litigation in 2005 so Interim Guidelines would drain Lake Powell before they took shortages, says the same thing I’m saying:

https://www.varuna.io/LOTR/2012/Guenther_Arizona_Water_Talk_2012.pdf

Look for the slide where he admits they are overusing tributary water and Upper Basin will litigate it.

I’m reading this new book on Imperial and QSA. It’s pretty good though it’s heavily biased towards Imperial farmers, Morgan is a water engineer who worked with the Abatti brothers (they farm more than 7,000 acres in Imperial) in their 20 year litigation fight with IID and everyone else trying to transfer their water to cities:

https://www.amazon.com/Morality-Deceit-Californias-Quantification-Settlement-ebook/dp/B0BN7662TC/

I reproduced the SNWA Loss Study when it came out and its slanted. The glaring part is they are trying to charge Imperial and everyone else below Parker Dam for the evaporation losses on Lake Havasu. That lake is there for Metropolitan and CAP to pump from, the losses belong to them, not everyone below it. SNWA shouldn’t have done the study. It instantly politicized it since they are the big winner sitting at the top of the Lower Colorado, and CAP/Metropolitan are close behind. Where they got the corridor losses for Reach 4 is unclear, they are counting only losses and not the inflows which are substantial in the Grand Canyon. The Bureau 24 month reports track them in each reach but mysteriously stop at Parker Dam. If they are going to do that loss study they need to do inflows, losses AND WHERE THE LOWER BASINS HALF OF THE MEXICO III(c) obligation ACTUALLY COMES FROM.

Eric Kuhn tells me the committee that drafted the Upper Colorado Compact unwisely let Charles Carson, AZ lawyer and trouble maker, chair the drafting committee based on the miniscule 50,000 af AZ have in the Upper Basin. That may have contributed to the punitive language on curtailment in the compact, which is very favorable to the Lower Basin to get uninterrupted flows. Carson was the AZ ally to Stone, Breitenstein and Tipton and their Caliphobia in the 40’s. This is the illuminating letter he wrote to Cordell Hull(Secretary of State) backing the Mexico Treaty:

https://www.varuna.io/LOTR/1944/Carson_to_Hull_1944.pdf

Everything I’ve read Upper Basin should have switched sides and joined California against Arizona once CA agreed to the 4.4 limitation. They sure shouldn’t have forced the Mexico Treaty on California and themselves. The tragic mistake on the Mexico treaty was sequencing. With 20/20 hindsight they should’ve:

Built the All American canal to remove Mexico’s leverage,

Negotiated the treaty,

Then built Hoover Dam to regulate the river flow which dramatically

expanded use with year round irrigation in the entire Lower Basin

George, just wondering if California has reservoir capacity to store water that comes to them from the sky. They are, as usual, leading the pack this year with record rains and now record snow. I read today that heavy snowfall is expected between San Diego and Los Angeles – between 5 and 8 feet. I can’t even imagine what 5 feet of snow do to Los Angeles. But they have already had huge amounts of rain and now snow. I guess most of it will just go out to sea.

California has quite a lot of storage, but more of it in the northern parts than the southern; they will probably fill a lot of it this year, although like the Colorado River Basin they’ve been in a drought situation. For whatever falls on LA and San Diego (and the San Gabrielle Mtns that will get most of the snow), you’re right: most of it will just go out to sea. But Los Angeles is pushing hard at present to turn the city back into a big earth sponge, with landscaping designed to hold the water to sink in rather than running off. The Guardian had a big story about that today: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/feb/27/parched-eco-architecture-los-angeles-megadrought-water-capturing-parks