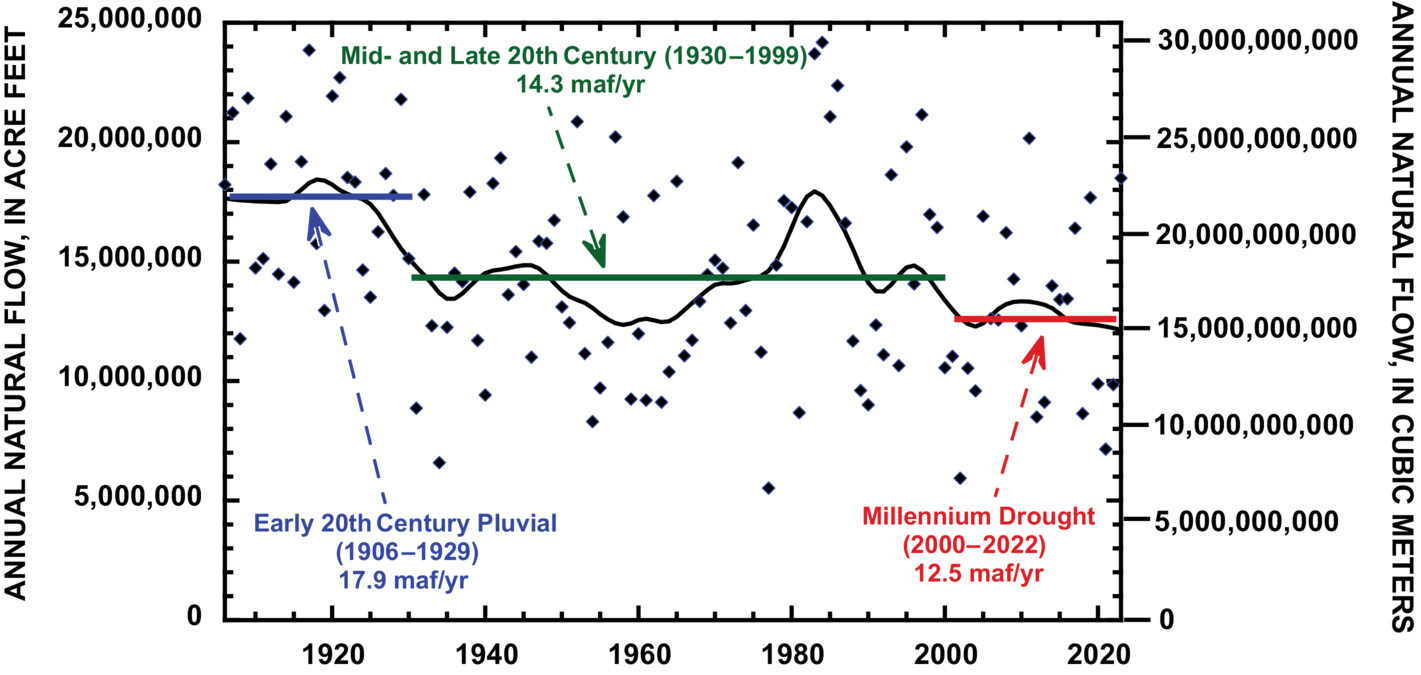

The graph above is from a study released a couple weeks ago, mid-June, on ‘The Colorado River Water Crisis: Its Origin and the Future,’ authored by two elders of Colorado River affairs: Dr. John Schmidt, river scientist at Utah State University, and Eric Kuhn, longtime manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District, now retired; both are deeply immersed in the river’s issues, and committed to working through the current crisis to a more reality-based future for the river and those who use its waters. A third author is Charles Yackulic, a noted scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey, but not so well known in Colorado River matters. When Jack Schmidt and Eric Kuhn speak about the river, everyone listens – especially when they speak together.

This graph alone explains a lot of the pain and anxiety we’ve been experiencing, and anticipating experiencing, in the Colorado River region – the natural basin plus technological out-of-basin extensions. (Sometimes the anticipation of pain can be more painful than the actual eventuality – try to think ‘dead pool’ without a serious twitch.)

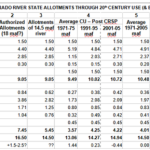

The black line meandering through the graph is a smoothing curve tracing the general up-or-down-and-how-far of the erratic annual flows of the river (the little black dots peppered all over the graph). But the genius of their analysis is in the three horizontal lines. They’ve divided the 117 years for which we have some semblance of measures for Colorado River’s flows into three fairly distinct periods: The Early 20th-Century Pluvial (two-bit word for ‘really wet period’) when the river averaged almost 18 million acre-feet a year (maf/yr) for a quarter-century; then the six-decade Mid to Late Century period when the river averaged 14.3 maf/yr; and then what they’ve chosen to call the Millennium Drought in which the river has only averaged flows of 12.5 maf/yr. (I would just call it ‘The Anthropocene.’)

In terms of flow, that might be three different rivers. The large-scale management of the Colorado River began with the Colorado River Compact in 1922, created just past the peak of the Early 20th-century Pluvial; it was written for the ‘first river,’ as it was then. It’s true there were scientists like E.C. ReRue saying that tree rings indicated that the pluvial period was highly unusual, and 12-13 maf might be a better average flow when the river had a lot of pooled up storage and irrigation water spread out to dry under the desert sun…. But try telling that dour perception to a bunch of engineers and city-builders in the Early Anthropocene, sitting with their new-fangled bulldozers idling on the banks of a wild river running 18 maf a year….

As the river slipped into the severe drought of the 1930s, and the rest of the 20th century where the average flow was less than the 15 maf that had been divided in the Compact, to say nothing of the 1.5 maf for Mexico, it still seemed possible, with the addition of new elements in what became known as ‘The Law of the River,’ to continue governing that ‘second river’ more or less by the Compact. But it was an increasingly shaky situation, saved mostly by the fact that the Upper Basin states were using quite a bit less than their 7.5 maf/yr, and the water they weren’t using was pooled up in not one but two huge reservoirs that were occasionally both full.

But when the Millennial Drought struck just after the turn of the century, the ‘third river’ was born, its flows 40 percent lower than those of the ‘first river,’ things began to fall apart….

It’s interesting that the publication of this study more or less coincided with news releases about the official beginning of meetings to work out a new management regime for the Colorado River, to be in place by the end of 2026. There is nothing mystical or even historical about the choice of 2026 for this; the date stems from the fact that, early in what Schmidt, Kuhn and Yockulic call the ‘Millennial Drought,’ the managers of the Colorado River storage and delivery systems realized they were in trouble. After a really bad water year in 2002, followed by half a decade of mediocre-to-pretty-bad water years, storage in the River’s two big ‘fail safe’ reservoirs had dropped from near-full in 2001 to half-full. So the managers gathered in 2006 to work on new river management stratagems – beginning by creating ‘Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead’; the ‘interim’ for the Interim Guidelines would be two decades, to 2026, at which time they planned, or at least hoped, to have a new river management plan.

Management for all three of the rivers portrayed on the graph has been done under the auspices of ‘The Law of the River,’ the bag of compacts, treaties, laws, court decisions, state resolutions, federal regulations and other elements, that have accumulated over the past century around the original 1922 Colorado River Compact, to clarify, interpret, legislate, and otherwise support the Compact. The ‘Interim Guidelines’ went into the bag with the rest of the Law of the River – as did a set of Drought Contingency Plans (Upper and Lower Basins) in 2019.

But now – practically on the eve of 2026 – storage has continued to drop so alarmingly in the Mead and Powell Reservoirs, despite cuts in consumptive use under the Interim Guidelines, that last summer the Bureau of Reclamation and Interior Department issued a semi-panicky mandate that, to fend off the possibility of going to dead pool in the big reservoirs, it would be necessary to cut consumptive uses much more – by 2-4 maf/yr, a huge cut.

This has engendered several plans, the most popular of which would produce a reduction of three maf over three years – only half of the Bureau’s minimum request – and would require the federal government to pay $1.2 billion to get it done. This plan will probably be accepted, however, even though it too may prove insufficient to get us on to 2026, partly because any of the other plans would probably end up in court for the next decade, and partly because we just had a big fat pluvialish year of snow in the mountains that will give a stay to the increasingly scary decline in the big reservoirs.

This new agreement to reduce use will go in the bag along with the rest of the Law of the River. The question then becomes – what will happen in 2026? Will we just be adding another set of patches, bandaids and crutches to the Law of the River bag, to keep the 1922 Colorado River Compact propped up and somewhat afloat?

When I think of the Colorado River Compact today, I think of the 1950 Chevy I bought for $50 in 1970-something from an old guy in Crested Butte. After driving it for a couple years, it started running worse than usual, so I took it to the garage to see what the mechanic recommended.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘if it was mine, I’d jack up the radiator cap and put a better car under it.’

That wasn’t exactly what I wanted to hear. And there are still a lot of people who think the Colorado River Compact is still just fine, with a little help from the Law of the River bag of tricks. People who say it would be impossible to replace the Compact, and don’t want to hear of it.

But look at the graph. The Colorado River Compact was written for a river that for a quarter century was running an average of 17.9 maf. Now it is a considerably different river. There is one sentence in the Colorado River Compact we ought to revisit – its first sentence:

‘The major purposes of this compact are to provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System; to establish the relative importance of different beneficial uses of water, to promote interstate comity; to remove causes of present and future controversies; and to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property from floods.’

Wouldn’t it be nice to have a Compact for managing the river we have now that did all of those things? The 1922 Compact really only fulfilled the fourth objective; it sufficed to ‘secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin,’ so long as Congress was willing to ignore that there was ‘interstate comity’ with only six of the seven states, and there were plenty of ‘present and future controversies’ lurking in the wings.

The commissioners had also failed in their original intentions for ‘providing for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters’. What they had wanted to do was to effect a seven-way division of the river so that each state would know that, when it was ready to go into super-growth mode like California already was, there would be water for them to develop. Essentially, they wanted to abrogate the appropriation doctrine at the interstate level, so that one state (California) could not preclude development in the other states.

They spent most of their first week of compact commission meetings trying to work out that seven-state division, but they were all so full of their own big dreams that it would have required a couple ‘first rivers’ to fulfill their hopes. The two-basin division of the river they eventually settled on sufficed to get the Boulder Canyon Project underway, but was not what they had hoped to do. It did give the Upper Basin states a temporary sense of relief, until the drought of the 1930s made them realize the implications of the ‘shall not cause the flow to be depleted below’ clause, which afforded plenty of potential future controversies; the Lower Basin states, meanwhile, found immediate cause for controversy, with Arizona soon suing California.

All of this makes me think it may be time to, as it were, jack up the first sentence of the existing Compact, and create a new Compact to put under it, one that actually accomplishes the three worthy stated objectives that remain unfulfilled.

Also in the news last week was the announcement that The Supremes, our jolly kick-ass band of judicial activists, have delivered another kick to some of the First People in the Colorado River basin. We’ll begin to delve into that in the next post here….

The problem is the same as amending the US Constitution: the bad guys play a LOT dirtier than the good guys. I don’t know if there is a way to get doable guidelines to fix what’s broken. I fear many of us won’t live to see the result. Rollie Fischer didn’t.

Info for Readers: Rollie Fischer was Director of the Colorado River Water Conservation District before Eric Kuhn.

Dividing flow by volume lends to wastage or shortages. Seldom comes out right.

California’s inaction on saving for a non-rainy day enhances their issue of not enough water.

With our country so politically divided, real solutions to real problems are impossible to come by. Our country is of three colors, not two. Red, white and blue.

The “big, fat pluvialish year” just ended may be more curse than blessing. One more of those, and good luck convincing the can-kickers that a crisis loometh.

It begins to look like one fat year was enough – don’t need another one….

Love The Supremes comment. May I quote you?

Sandy

Painful all right! But not a bit surprising. Anybody who thinks rivers are all going to start running strong any decade now is living in fantasyland. Keep it up, George. ken

Kudos, George. Just now getting to reading this post, but well worth the wait.

Carry on,

Carl