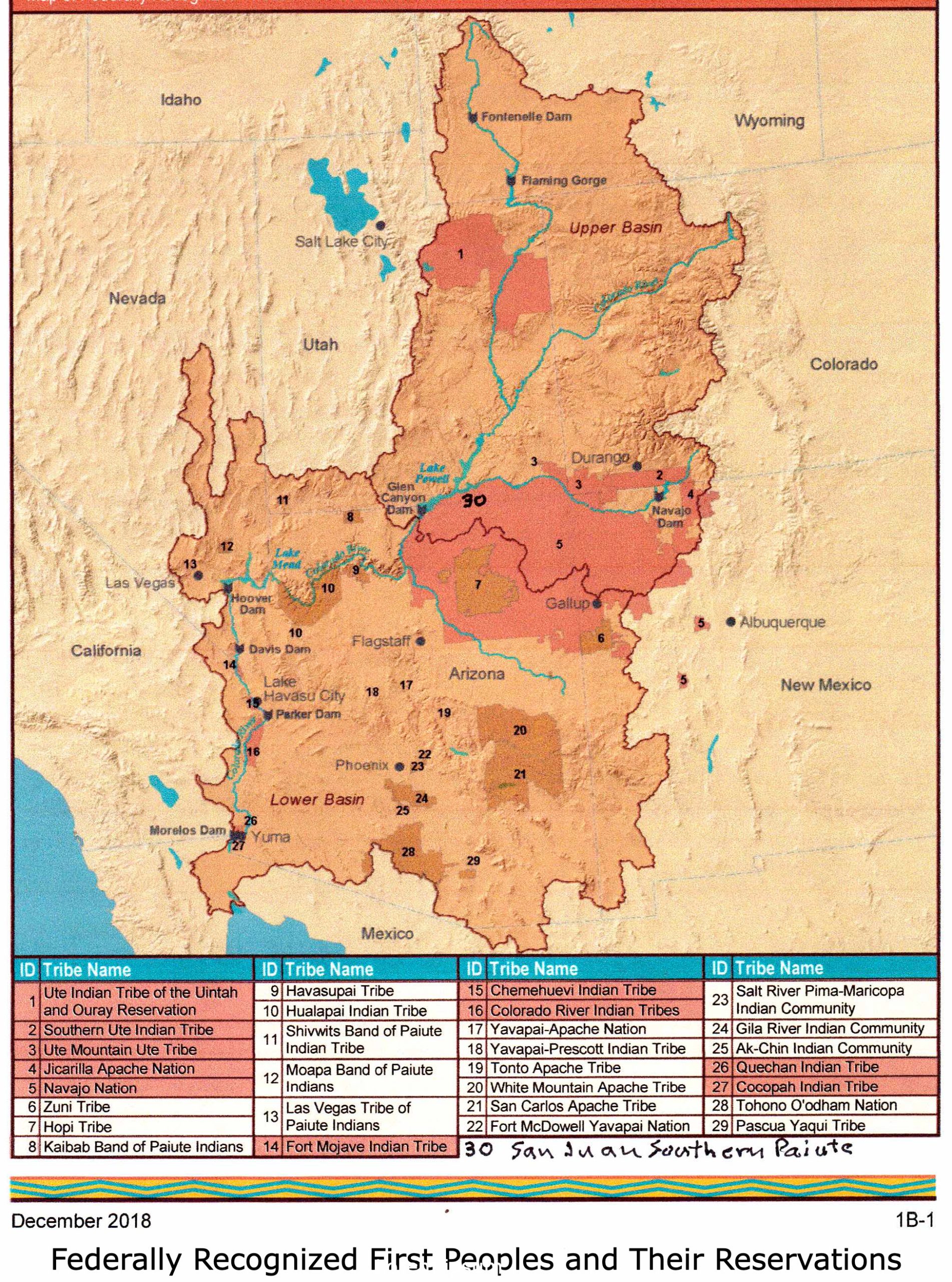

The last post here began an exploration of tribal issues in the Colorado River region, where 30 ‘First People’ nations have been put on reservations throughout the region. We looked at some of the precolumbian history in the Southwest, to emphasize the human diversity that existed in the region when European peoples invaded the continent beginning 500 years ago. ‘The Second People,’ I guess we could call the invaders – a single people instead of many like the more than 700 distinctive First Peoples; most of our ancestors seemed willing to let go of their Old World identities and assimilate to a common ‘American dream’ in the New World, e pluribus unum. This does not mean, I hasten to add, that we consistently act as ‘one people.’ But our differences today are ‘New World conflicts,’ not those stemming from ‘Old World’ distinctions between English, French, Italian, Spanish, Slavic, and the other hereditary European national stocks.

From the beginning till now, the relationships between the First and Second Peoples have been mostly ambiguous at best. Until the 20th century CE, their interactions almost always devolved into conflict and warfare, conflicts the native people always eventually lost, despite occasional battle victories, to the sheer mass of the invaders and their superior firepower, not to mention their virulent diseases unknown in the New World.

The conflicts were eventually settled with treaties in which the First Peoples, one by one, yielded most or all of their old hunter-forager territories to the invaders in exchange for much smaller ‘reservations’ managed through a ‘trust’ relationship with the United States government. In the best resolutions, the First People got the least desirable part of their former homeland as their reservation; in the worst resolutions, they were forcibly moved to strange and generally undesirable places beyond the settled area. Out of sight, out of mind.

In its broadest terms, a ‘trust’ is a legal arrangement between a benefactor and a beneficiary that is administered by a trustee. Given that the reservation trust arrangement had the First People giving up most of the land they had inhabited for many generations, in exchange for a small piece of that land and freedom from further invasive pressure, one wonders who should be called the benefactor and who the beneficiary.

But the trust arrangement between the First and Second Peoples was defined in 1831 by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, in deciding a suit filed by the southeastern Creek Nation against the State of Georgia. The Creek People were one of the ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ in the southern states who had tried hard to fully assimilate to European ways: taking up farming, speaking English, even dressing European – and being civilized enough to know they needed to lawyer-up in civil situations like loss of their land. But they were still ‘Indians,’ and therefore subject to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, to free up more land for white settlers.

When that suit went to the Supreme Court in 1831, Chief Justice Marshall – probably the first real ‘activist justice’ – declared that all situations involving the First Peoples should be negotiated and resolved as between nations, not within state jurisdictions. But it would not be nation-to-nation negotiations between equals. The First Peoples he declared to be ‘domestic dependent nations’ whose ‘relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to his guardian. They look to our government for protection; rely upon its kindness and its power; appeal to it for relief to their wants; and address the President as their Great Father.’

There is a sad irony to the fact that this articulation of a guardian-ward relationship concluded with the ‘Five Civilized Tribes,’ who had tried to follow the ways of their ‘guardian’ nation, removed from their homes and force-marched on the ‘Trail of Tears’ to strange lands across the Mississippi. More power than kindness.

An Office of Indian Affairs was created to administer the reservation trust model; the nature of the trust relationship is indicated by the fact that OIA was in the War Department. In 1849 the Interior Department was created, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs was moved into that.

Devastated as the First Peoples were at that time by European diseases, continual conflict and retreat before the waves of ‘unsettlers’ swarming over the continent, the ‘guardian-ward’ foster-parent relationship was probably an accurate enough description of the reservation life imposed on the First Peoples: a relationship historically marked at best by what could only be described generously as tough love, too often by blatant exploitation, and most often by indifference and negligence. That they survived at all with so much of their spiritual life and heritage still burning within is a measure of the cohesive strength possible in small tight societies that mass societies can never really achieve.

Through time, the undercurrent of vengeance leached out of the trust relationship, but a full legal definition of the trust remained somewhat ambiguous, and the treaties on which the trusts were based had varying degrees of legal explication. And until well into the 20th century, the reservation trust relationship was rooted in a belief – a benefactor belief, of course – that the best resolution for all concerned was total cultural assimilation of the First Peoples – essentially, elimination of them as distinct peoples: it was no longer ‘kill the Indians,’ but ‘kill what’s Indian to save the people.’ This included measures like the 1887 Dawes Act that ‘subdivided’ the reservations into individual plots to make the Peoples understand the blessings of private property, and laws that moved children from their families to boarding schools where they were given haircuts, immersed in industrial culture, and punished for speaking their own language. This was all done with a virtuous sense of Christian duty to the heathen.

The 20th century also saw some of the worthless land the First People had been relocated to turn out to have valuable deposits of oil and gas, uranium, and other basic industrial resources. The Peoples were of course judged to be unable to develop and manage these resources themselves, so that was done under the trust by the BIA and other Interior agencies, with all the revenues supposed to go to the Peoples of the reservation exploited: some into tribal funds, and some into individual funds where the reservation had been successfully subdivided – funds to be kept separate from other expenditures and revenues associated with regular reservation activity.

This was a daunting accounting challenge, but the BIA seemed to go above and beyond the challenge in messing it up. By the 1990s, it was obvious that this was a complete mess, and a $100 billion class action suit was filed in the mid-1990s on behalf of all the tribes and half a million individuals who should have been getting resource revenue, but weren’t. Investigation showed an array of misdirection of funds, malfeasance on the part of some of the private contractors holding back funds, some money just going into the general treasury funds, but mostly it was just terrible non-management of the trusts.

The judge who evaluated the $100 billion suit came up with a figure of only $455 million. Faced with the probability of a court appeal, keepng a truly embarrassing situation in the public mind longer, Interior offered a settlement of $1.4 billion in direct payments, plus $2 billion to try to unsnarl some of the Dawes Act reservation fragmentation, and a $60 million scholarship fund to educate reservation youth.

But – meanwhile, what about the most important western resource for the reservations: water? (You knew I’d eventually get around to it.) In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered a seminal decision on water for reservations, to resolve a Montana water situation, that was really the first government action showing empathy for a First People trying to make a life in circumstances made difficult both by antipathy from the larger society around them and by the always ambiguous trust relationship with the government.

Early in the 20th century, Montana settlers had began using water from the Milk River above the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation (north of the Missouri River, primarily Gros Ventre People). The settlers were told to stop because it was taking water needed by the First People in their own efforts to become ‘civilized’ farmers. The settlers – faced with the possible loss of their own land, worthless with the water – sued, Winters v. the United States; and the case went to the Supreme Court.

The Court affirmed that the water the settlers was using belonged with the reservation, even though the Indians were not using all of the water yet, and had filed no appropriation claim on it. When the federal government reserved land for some purpose, the Court declared, such as the settling and ‘civilizing’ of a People, the reservation of a sufficient quantity of water to carry out that purpose was implicit in the reservation of land. The water thus reserved, with creation of the reservation, was to be exempt from appropriation under the laws of the state in which the reservation was located; and the appropriation date for that reserved water would be the date of creation of the reservation, whether the water was yet being used or not. Given that most reservations were created before their former land was opened to settlers, these became very senior water rights – and the right didn’t even require the water to immediately be put to beneficial economic use; it was to be there whenever the reservation People were ready to learn to use it.

One can imagine the shockwave this sent through the arid West where appropriation law was foundational to practically all development – first come, first served for the use of water, so long as the claim was properly filed and adjudicated. Now the federal government, which still owned most of the Interior West and Southwest, was being given, by the highest court in the land, the prerogative of elbowing its way to the front of the line by reserving land for specific purposes thar required a quantity of water.

The Supreme Court that issued the Winters decision may have engaged in a little judicial activism – taking upon itself something that would have been more properly addressed by Congress. But the Court essentially argued that its decision was obviously implicit in the Congresssional ratification of each reservation: Congress would surely not ‘take from [a First People] the means of continuing their old habits, yet not leave them the power to change to new ones’; therefore the reservation of the water along with the land was surely presumed by Congress. This may be a more idealized view of the rationality and integrity of Congress than many people then or now have, especially where the First People were concerned, but so the Court decreed. It was basically a majority of justices making a judgment call on behalf of equity, fairness and decency: how could the nation take away the free-ranging hunter-forager way of life from the people of another nation, and not give them the wherewithal to forge a new, more ‘civilized’ way of life?

The Winters decree did leave the First Peoples with a couple of difficult challenges, however, and no instruction on how to address them. They had to get their water rights quantified, in order to begin planning their development – and how much water did it take in the desert to convert a whole people to agricultural and industrial civilization? Then they had to figure out how to finance the development of their rights. And they had to do both of these things in a larger water-culture environment less than happy with the whole Winters decision.

This is where the ‘trust’ relationship with the federal government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, should have worked better than it in fact has. Next post, we will look at some of the trials and tribulations the First Peoples in the Colorado River region have experienced in working through those two challenges – a struggle most recently manifested in June this year, with a new Supreme Court decision declaring that, the Winters decision notwithstanding, nothing else about the trust relationship can be considered implicit in the fumbling-forward effort to work out the whole relationship of the First Peoples and the Second People. If something like assisting in determining a People’s basic rights isn’t explicit in the century-old establishing treaties, then no trust responsibility for that exists.

***

Great piece! Important one. Increasingly I have come to the belief that the Second People will have to learn, ;to a considerable degree, how to live as ‘civilized’ FIrst People used to. That is, an earth with 1 billion people or so will have to learn to live in a manner somewhat like the primeval ones (albeit, with Iphones, etc.

ken

George, I’m thoroughly enjoying your succinct, discursive exposition of such a complex dynamic. I had no idea that Montanans had contributed to a possible solution to the repeated violation of “trust” implicit in the larger mechanism of treaties with First Peoples. Since we now live in those environs, I can see that: we’re impressed by the State’s insistence for treating the rights of the individual as sacrosanct across the playing field (ranging from militant Constitutionalists on the one hand but also stretching as far as protecting the individualist’s rights for pro-choice on the other extreme).

George — Great recounting, as usual. Was wondering if you had seen the book “Blood Struggle,” by Wilkenson, which lays out these issues very well as “nation to nation” understandings. I used it as a central text in my classes at Evergreen a few years ago working with the Muckleshoot band of the Puyallup people, an assignment I very much enjoyed and learned a lot from. BTW, the Muckleshoot, for what it’s worth. really did want to be called “Indians” and held the moniker as a badge of pride. I look forward to more. Best regards, Peter

RESPONSE: Thanks for the book reference, Peter. Russell Means, a leader in the American Indian Movement of the 60s & 70s, agreed with the Muckleshoot:’One thing I’ve always maintained is that I’m an American Indian. I’m not a Native American. I’m not politically correct. Everyone who’s born in the Western Hemisphere is a Native American. We are all Native Americans. And if you notice, I put American before my ethnicity. I’m not hyphenated….’ My personal feeling is that it is one thing for the First People to call themselves ‘Indians’; another thing for me to do it. Knowing I’m writing to a mostly Euro-American audience, it seems better to remind us all that they were, in fact, the First People here….

Thanks for clarifying this unknown bit of current history.