Note in passing: this is the 50th post on this ‘weblog’ (a meaningful number to a ten-digit species). I am grateful to those who continue to open and even read these posts. I am obviously writing as much for my own edification and clarification as for yours, in the spirit of British writer E.M. Forster, who said, ‘I don’t know what I think until I see what I write.’ Working it out on paper, as we used to say, except now it is electrons on a screen only a little more organized than a starry night.

Most of these posts have been about the Colorado River – a river I can say I ‘love’ in all the complexity that concept of engagement encompasses. I love its natural forms and contours, which leave me thinking that we need a ‘sur-’ category for nature – ‘surnature’ like ‘surreal’ is to ‘real’ – for natural phenomena that seem to be ‘beyond nature,’ at least as we usually seem to think about nature, a fragile china shop in which we have sometimes behaved like a bull; here the river often seemed to be the rampant bull.

I am also fascinated, mystified and sometimes horrified by our often surreal engagement with this river and the geography through which it runs, from the mountains where we’ve pushed into the high rock and ice with conveyor lifts for recreation; then through the region of canyons and floodplains where a pre-urban agrarian culture contends unsuccessfully with a post-urban refugee culture trying to figure out what it wants to be; then into the serious canyons where the river in full patiently works at filling in silt behind some temporary (in river terms) structures built to teach the river to stand in and push rather than cut and run during their river-moment; then out onto the hot deserts where we’ve spread the river out in all directions to grow food, feed, and megacities where 20-25 million people live in a luxuriant culture they are just beginning to learn may be as fragile and ephemeral as any china shop in a bullish world.

The world we have made here is our fathers’ world; I am a son of homo faber, man the maker, artisan, artificer, engineer; but my mother was of the homo sapiens clan, men and women who stop, look, listen and think about what they see before rushing into action. With homo faber leading, we have created what looks like miracles in the deserts, but on a ‘buy now pay later’ plan; our miracles now start looking a little short-term, either from the changed environment or from just wearing out, or both, but we will still be paying for them as far into the future as we can see. Our challenge now is for homo faber and homo sapiens to work more in harmony: to stop, look and listen to envision how we can carry forward what we do well with the foresight to avoid what we now know we do badly, accepting that the river and its world are not inert, but have their own standards, not self-evident but discoverable: standards we should learn before we challenge them in this unpredictable ‘surnatural’ mix of utility and beauty because nature can dispassionately punish, withhold, destroy. We’ve no choice but to keep moving what we hope is forward, but remembering the maze that’s the great seal of the Salt River Maricopa and Pima People; don’t expect anything to be easy and fast, like the 20th century appeared to be. Chronicling and analyzing where we are and what we do is the purpose here – on to the next 50.

That noted – back to the river. Lots is happening and not happening along the Colorado River these days, some of which you’ve been seeing in the national news. One of the notable things happening and not happening is the almost unbelievable fact that the Navajo People, the Hopi People, the San Juan Paiute People, and the People of the State of Arizona as well as We the People (as Indian trustees) have finally negotiated a settlement on water rights for the three-in-one reservations – the huge Navajo Reservation covering a tenth of Arizona and parts of New Mexico and Utah, and the smaller Hopi and Paiute Reservations contained within it. Unfortunately this very complex settlement still needs the approval of Congress, and carries a five billion dollar price tag, so we will wait till that happens, or doesn’t, to look at it more closely.

The most important thing that is not happening along the river today is the impasse in negotiations between the seven Colorado River states, in their efforts to figure out how to manage the river in the post-2026 epoch, when the 2007 Interim Guidelines for managing the river in the early 21st century expire (along with the 2019 and 2022 Interim Interim Guidelines required to limp through to 2026). Looking over the negotiators’ shoulders very closely are the people of Mexico and the 30 First People tribes, whose rights to water are all shoehorned into the seven state allotments and appropriation systems – and the 30 tribes have informed the Bureau and the states that they will not be ignored or shortchanged this time.

Negotiations with everyone more or less in the same room broke down early in 2024, and the seven states withdrew into their artificial Colorado River Compact division: the four states of the Upper Basin and the four states of the Lower Basin retreated to their redoubts above and below the mainstem’s canyons, to start lobbing proposals over the canyons at each other, each telling the other what they are willing to do in their Basin – and what they expect the other Basin to do in theirs.

Each Basin’s demands on the other Basin are, of course, more than the other Basin is willing to do, and everyone is stubbornly holding their ground. We’ll not go over their separate proposals again; a summary of the two Basin plans can be found here if you want a review. The only real step forward has been the Lower Basin’s willingness to finally take out of their own Compact allotments the ‘structural deficit’ – the Lower Basin system losses through evapotranspiration, bank storage, et cetera, and their half of the Mexican obligation.

There will probably eventually be another set of links in the Law of the River chain going back to the Colorado River Compact: either a complicated set of compromises worked out among the states of the two Basins, with lots of hoops for the Basin states tied to different reservoir elevations – or if that proves impossible, the Bureau of Reclamation will come up with another ‘interim plan’ to stagger a little further into the 21st century.

But all that is just kind of tedious, mundane – hardly worthy of the surnatural river and its environment we are now just trying keep up with. And – isn’t everyone saying we need to think creatively, ‘think outside the box’? So I want to look at an idea that’s at least up on the edge of the box looking outside it: the fact that we could actually do now – have almost done – what the Colorado River Compact commissioners could not do in 1922.

They gathered in 1922 to create an interstate compact that would preempt the appropriations doctrine at the interstate level; they wanted an equitable (not the same as ‘equal’) seven-way division of the river’s waters, so they could avoid being trapped in a seven-state appropriations race, with California already at the first turn while Wyoming and New Mexico were still looking for the starting gate. They wanted each state to know that it would have water to develop when it was ready for it.

They were unable to do that seven-way division, however, because they knew too little about the flow of the river, and even less about the future needs of their states. The best compact they were almost able to agree on was the last-minute field-expedient division of the Colorado River Basin into two basins, each with half of the river’s water to develop. At one point in the negotiations, the Commission chair and federal representative Herbert Hoover called the two-basin division ‘a temporary equitable division,’ postponing the more thorough division they had wanted for ‘those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information.’ The ‘temporary equitable division’ would suffice, Hoover believed, to ‘assure the continued development of the river,’ and it did; even though only six of the seven states ratified the Compact, Congress was persuaded that there was enough ‘comity’ among the states for them to authorize the construction of the Boulder Canyon Project.

But – ‘those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information’ – that’s us, isn’t it? Women now too, as well as men? We know a lot more about the river than we did in 1922 – a lot of it in the ‘sadder but wiser’ category of knowledge, but … haven’t we also, at this point, incrementally effected a seven-way division of the waters of the Colorado (including a share for Mexico, with the states responsible for fulfilling the Winters promise to the Indians with federal help)? Each state may not have all the river water it wants, and wanted in 1922, but we all know the river is now tapped out: each state has all the water it is ever likely to get; a seven-way division has happened, like it or not. And the quantity each has to use is reasonably close to the quantities codified in various elements of the Law of the River.

So, in other words – could we not finally draft the Colorado River Compact the original compact creators wanted to do, but lacked the necessary ‘fund of information’? Well, yes but…. That seven-way division is not so easy as writing down seven acre-foot numbers and saying ‘That’s all, folks,’ live with it. There are some rough spots that would have to be worked out, probably at the usual glacial speed of Colorado River decision-making.

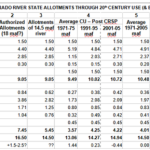

By my amateur calculations, for example, all three Lower Basin states and Colorado and Utah in the Upper Basin are using somewhere between 5 and 13 percent more water than their ‘Law of the River’ allotments when system losses are figured in – but that’s assuming a proportionate distribution of system losses, rather than distribution based on appropriation seniority, which of course under the two-basin system would allow California to dump its portion on Arizona and Nevada, and Colorado and Utah to legally diss Wyoming and New Mexico. But 5-13 percent is not a huge quantity, and should be negotiable.

Another rough spot would be writing the future into a new compact – a future that does not look so rosy as the future did to the original compact commission. Then, the idea of augmenting the river from other larger rivers was still alive; the commissioners thought that ‘those men who may come after us’ would be allotting more water, not less. Today, our greater fund of information lets us know that we will have less water in the future. So once the states’ current reality-based allotments are settled on, it will be necessary to convert them all to percentages of the current measured flow of the river, maybe as a ten-year rolling average. Then each state’s allotment would be reduced proportionally as the river flow decreased due to climate heating – or. if appropriation’s true believers (aka senior users) continue to rule the roost, with junior users taking the hit.

There would be other rough spots too, I’m sure. But it is obvious at this point that, when it comes to adapting either to reality (the system losses) or to the probable future, the first-come first-served appropriations doctrine as a foundational law is a box with high sides. The 1922 compact commissioners wanted to preempt it at the interstate level, and even California went along with that then because that agreement was the only way to get Congress to build the dam they desperately wanted. But that was then; California got its Boulder Canyon Project, and now doesn’t need to be nice; every time the idea of proportionate sharing of losses among the states comes up, California says first-come first-served or see you in court.

The other box we ought to be thinking outside of is nested within the appropriation doctrine box, the Compact itself, which only partially appeared to succeed in limiting interstate appropriation issues by supposedly giving the four states above the canyons half the river to develop on their own schedule (after working out their own interstate issues). Arizona, stuck in the lower basin with California, refused to even ratify the Compact, and spent three decades in court against California. And as soon as annual flows began to drop after the ‘pluvial Twenties,’ the Upper Basin states got increasingly testy about the ambiguous Compact mandate to ‘not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below’ the Lower Basin’s set share, or else – what? (Expect the worst; it’s California.) The Compact looked increasingly threadbare as the 20th century wore on. The 2007 Interim Guidelines to help the Compact limp through another two decades was amended by the Drought Contingency plans in 2019, and again by the panicky call for major cuts in use across the board in 2022, centennial year for the Compact – a downward spiral marked, in my mind, by California’s assertion of appropriative seniority over the other states in 2022, a mark of the lack of real progress in sharing the river since 1922. The history of the two-basin division has led inexorably to the current impasse.

Yet no one negotiating is suggesting that maybe it is time to start fresh post-2026, based on our accumulated ‘fund of information,’ and the realization that we could start by formalizing the seven-way division envisioned by the original compact commissioners. We cling to the Compact like shipwrecked sailors clinging to straws.

Maybe if we could at least hoist ourselves up the edge of the Compact box, and look out beyond it and the edge of the appropriations box, we would be able to look back to the surnatural river we had and, with our fund of greater information, see it for what it really is rather than what we imagined it could be – a desert river as well as a water source, with all the coyote trickery and surprises implied therein.

Stay tuned for ‘Outside the Box with the Desert River.’

A thorough examination of the history of water rights in the surrounding states which depend on Rio Colorado.

“Prior appropriation” never made any sense to me from the standpoint of either equity or sustainability. Maybe I had to be far west of the 100th Meridian in 1870 or 1920 for it to do so. In any case, it seems plausible to me that – if “possession is 9/10ths of the law” works as a guiding principle in some circumstances – then perhaps something vaguely similar can be made to work in the context of our very different 21st century circumstances. The word I keep coming back to is the one we often perform poorest at: sharing.

Sharing is very hard to do in an economy that fosters greed, but “very hard” is not quite the same as “impossible.” It does require that there be adults in the room as well as the usual shrill children, protecting the toys they perceive as their own no matter what.

Personal appropriation of property from the commons is – along with the concept of ‘individualism’ as a social philosophy – a concept invented, mostly as a self-justification by privileged classes in the Anglo-European ‘Enlightenment.’ We seem, at this point, to be likely to harvest its bitterest fruits this November. We probably only succeeded as a species in our first million years through what is now so often demeaned as ‘socialism’ even though we often live in communities that practice it constantly (everyone kicking in for roads, schools, parks, etc). We have to come around to what you call ‘sharing’ in the more abstract aspects of our lives, since we’ve run out of commons to privatize….

Thanks again, George. I’ll pass it along to my canyon friends.

Vince

Ah, but to be able to predict the future, restore the past, fulfill all needs and wants from the horn-a-plenty and ride horses that don’t buck.

Would a horse that had never bucked be a horse with any spirit? Just curious….

Looking forward to the next episode featuring Wily Coyote! Time to set the traps?

No traps; we just have to learn to live with him and his deserts, rather than trying to beat them….

This episode of Sibley’s Rivers has left me stopped, looking and listening more than any other episode for the simple fact that their is a hint of optimism and hope. There is an idea for a way to move forward toward a resolution. And that the indigenous peoples have won recognition of their rights is also a very positive sign that resolution is possible.

To the extent I am able to follow the complexity, this was a very good reading experience. I think you may be on to something here, Mr. Sibley. Thanks.

They way forward has to begin with learning the ‘settlement process’ from the First Peoples: the capacity to let go of the right to a lot of water that just isn’t there, and work with the reality around you…. We’re not quite there yet, but moving that direction….

“Surnatural” is an excellent term.

Leaving the future to “those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information” seems at once wise and foolish. There’s wisdom in knowing and acknowledging the limitations we all operate within, but leaving it to future generations seems to have allowed intervening generations to misuse the river, leaving those possessed of a greater fund of information dammed and damned.

Yes – If we go ahead and do what we want to do anyway (and Hoover, an engineer, really wanted to build the dam) without laying a good infrastructure for it, and leaving that infrastructure to ‘those who may come after us,’ we’re really giving them a messy situation. It’s like trying to put a new foundation under an old boom-town building built on a log at each corner – possible, but no fun, and it doesn’t always work.

Very nice. However, you left one part of the future ‘negotiations’ out—- “demand” must be lowered!

Unfortunately, saying ‘demand must be lowered,’ is a little like saying ‘lying in politics must be stopped.’

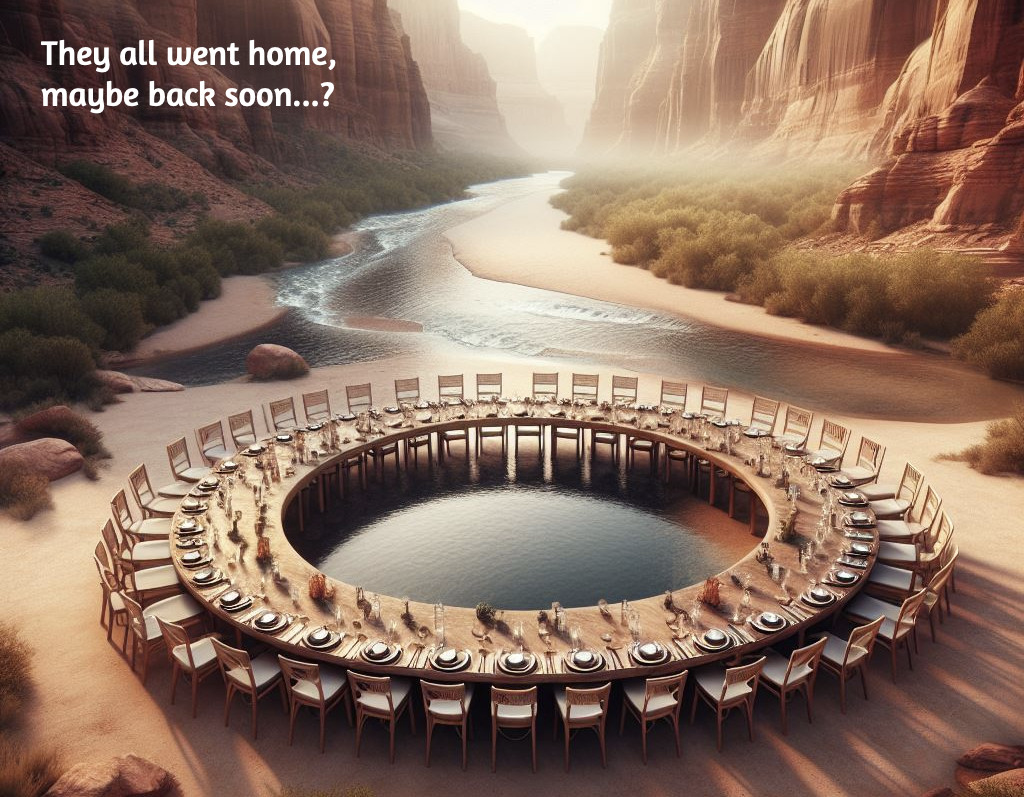

The big roundtable empty-chair non-gathering at the top of this episode?

I notice in the comments at least one suggesting there is optimism on display in this post. Optimism is a glory-hallelujah occurrence so seldom seen that I looked again. Maybe a little, but optimism and hope are signifying traits Sibley exhibits at perhaps too many opportunities. My take is, even after reading George all this way, is no, excitement for future come-togetherness is misplaced. Ugh! What a thing to say? Yes. What a thing to believe? Just an awful load to carry.

But congratulations are truly in order. That is, 50–count ’em, 50–posts from this guy still going so strong way past his allotted three score and ten that the achievement becomes near-legend. But nay! It’s the God’s truth. Way to go, Sibley, and keep ’em coming and us reading.

The parties will reassemble all right, down by the riverside; I did not mean to say that would naturally result in a positive outcome, so there may have been a little misunderstanding there. I’m more inclined to think they will reassemble to cobble together another ‘interim link’ in the Law of the River, the chain that binds us. I think hope for real progress in living reasonably with the river will only come when they all agree to let one of the tribal elders begin their meetings with a prayer to (for?) the Great River.