Humpty-Dumpty just sat on a wall,

But Trumpty-Mumpty started a brawl;

And fallout from the brawl

Like the fall from the wall

Might never go back together at all.

I was chastised by a couple readers after the last post: you’re just giving the Trumpty-Mumpty dynamic duo what it wants by focusing on what it is doing. What we want to know is what this is going to mean for us out here in the arid lands, and thoughts on what we should be doing about that. What does it mean here in the Colorado River region?

This led me to wonder: is focusing too much on what nasty people are doing just another form of surrendering to them? In chess, and probably all other competitive sports, there’s the matter of the ‘impetus’: one player or team of players will achieve the point in a game where they are ‘calling the shots,’ forcing the other player(s) to react to their strategies rather than pursuing the others’ own game plan. Players with that impetus will usually win, so long as they don’t lose that impetus through some misplay of their own.

The Trumpty-Mumpties have certainly seized the impetus in America’s 250-year ‘game’ of trying to work out a collaborative governance for the American nation-state; and our response so far has been railing editorially at them, or suing them, or just kind of watching in shocked silence as they break things. ‘Roll over and play dead,’ was the recommendation of one prominent Democrat for his party; let the Repugnicans dig themselves into a hole they can’t get out of, then get up and kick the debris in on top of them. The trouble with that is the fact that the debris will be our dismantled constitutional government, and as was the case when Humpty-Dumpty had his great fall, all of us (and our horsepower) may not be able to put it back together again. When one of Mumpty’s ‘Space X’ rockets blew up shortly after blastoff a few weeks ago, his company described it as a ‘rapid unplanned disassembly,’ a wonderful bit of euphemistic language. What we are watching happen in our government is a ‘rapid barely planned disassembly,’ giving a little credit to the ‘Project 2025’ planners who knew their Repugnican wet dreams only stood a chance if they hit the ground running and ‘flooded the zone.’

So what can we do besides watch it happen, and express our dismay and horror? While we still can?

One thing we ought to do is to confront our own complicity in what is happening to us. American historian and philosopher Heather Cox Richardson started one of her daily columns (3/21/25) with the recollection of a really interesting commentary on our times reported twenty years ago by journalist Ron Suskind. A commentary that many of us may have encountered before, but it is really worth revisiting in the murky light of what’s happening today – here’s the paragraph from her column:

These days, I keep coming back to the quotation recorded by journalist Ron Suskind in a New York Times Magazine article in 2004. A senior advisor to President George W. Bush told Suskind that people like Suskind lived in “the reality-based community”: they believed people could find solutions based on their observations and careful study of discernible reality. But, the aide continued, such a worldview was obsolete. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore…. We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

This is something for us to ‘study,’ the 35-40 million of us who depend to some extent on the water of the Colorado River – First River of the Anthropocene Epoch. Suskind’s unnamed presidential advisor basically articulated the attitude that drove the first century of the Early American Anthropocene – and the development of the Colorado River, one of several places where the imperial business of ‘creating a new reality’ overriding the existing ‘discernible reality’ began. (The Panama Canal and the Columbia River being two other sites for the ‘Early American Anthropocene.’)

The history of the development of the Colorado River in the first two-thirds of the 20th century is the story of how we began to ‘create our own reality,’ and that story is told in the evolution of the Bureau of Reclamation. The Bureau came into being as the ‘Reclamation Service’ as part of the ‘Newlands Act’ of 1902. The Service had a modest mission, working with communities of desert homesteaders to develop the irrigation systems that would make their land arable.

The Reclamation Service came into being as part of the United States Geological Survey – very much what Bush’s advisor called a ‘reality-based’ organization, grounded in the scientific belief that ‘people could find solutions based on their observations and careful study of discernible reality.’ The USGS had essentially been given its operating ethos by John Wesley Powell, a consummate scientist whose observations and careful study of the arid lands led him to make policy recommendations as director of the USGS that fell afoul of the West’s industrial movers and shakers, and got him fired from that agency.

The scientists who had escaped the Powell purge, however, continued the ‘reality-based’ scientific discipline Powell had established for the USGS, and that was the science-based agency into which the Reclamation Service was placed in 1902. But the mission of the Reclamation Service was to help farming communities develop irrigation systems – essentially an engineering assignment.

The challenge in the Lower Colorado River deserts, for both the scientists and the engineers in the USGS, was learning to live with a water supply that ran in a flood for two or three months of the late spring and early summer, then became a comparative trickle the rest of year. The scientists and the engineers responded to that challenge in different ways. For the scientist, it was a challenge of adapting crops and plantings to what would grow in flood-mud, and spreading the muddy flood out accordingly. For the engineer, the challenge was to change the water supply, storing it to release it in more manageable full-season flows for growing whatever the farmers wanted to grow.

In short, the challenge was perceived to be either using science to adapt the human culture to whatever nature provided (however erratically), or using engineering and other related skill sets to adapt nature to provide whatever the culture needed or wanted. And in the early 20th century, with America just really learning how to use fossil fuels to construct an industrial civilization like the world had never seen…. We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality….

Perceiving that choice, the Bureau quickly grew impatient with trying to adapt local community irrigation systems to the wild Colorado River. By 1905 they and their emerging technology were ready to spread their wings, take on the imperial challenge of changing the river. In 1905 they stretched their legislated local charge by taking on three projects with a regional scale: a large (for its day) masonry dam on the Salt River to control flooding and store irrigation water for growth in the Phoenix area; an irrigation weir almost a mile wide across the Colorado mainstem above Yuma, Arizona, to keep water levels up for late-season irrigation water; and a five-mile transbasin tunnel in the upper reaches of the river, carrying water from the Gunnison River to the Uncompahgre River valley.

In 1907, halfway through those larger, more regional projects, the Reclamation Service left the Geological Survey, and became the Bureau of Reclamation, an independent agency in the Interior Department. Basically, the engineers left the scientists to their methodological study of ‘discernible reality’; they were ready to roll their own realities. They dreamed of the structures that would break the Colorado River to harness, and the other really big projects that would put the river to work making the desert bloom.

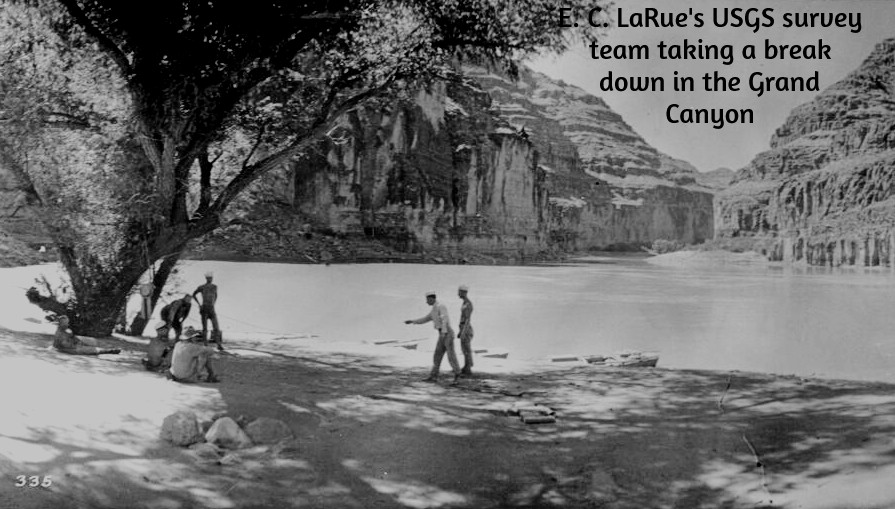

This never really became a declared war between the scientists and the engineers, but there was a distinct tension. When the seven Colorado River Basin states sat down in 1922 to divide the use of the river’s waters among themselves, they found conflicting opinions on how much water actually flowed in the river on average. Bureau engineers, including Reclamation Commissioner Arthur Powell Davis, were a frequent presence at the Compact Commission meetings; they had a 25-year record of flows at Yuma going back to 1896, showing an average annual flow of just under 18 million acre-feet for that short period. Meanwhile, E.C. LaRue, a USGS hydrologist and geologist, had been working on that flow problem for years, and had done some early work on tree rings and desert evaporation, leading him to believe that flows between 12 and 14 million acre-feet of usable water were a reasonable long range expectation for the river.

LaRue volunteered his assistance to the Compact Commission, but Commission Chair Herbert Hoover (the federal representative on the Commission, and himself an engineer) thought that would be unnecessary, and the Colorado River Compact used Bureau numbers – and within a decade, certainly within the century, the willful river had demonstrated that scientist LaRue’s stodgy old researched numbers were much closer to the real river we have contended with down to the present. River ‘elder’ Eric Kuhn and journalist-historian John Fleck wrote a book, Science Be Dammed, exploring this tension between the scientists and the engineers in creating the Compact, for those interested in a more detailed account of that.

But for my story here – the Bureau did go on to ‘create its new reality.’ The 1928 Boulder Canyon Act, as it unfolded, became a lamp in the darkness of the Great Depression. Private capitalism – probably our least democratic economic engine – had failed utterly to deal with the Depression, but federal funding coupled with private initiative under the direction of the Bureau put thousands of people to work, building not one but three big structures on the Colorado River mainstem: Hoover Dam capable of storing two year’s flow of the river, Parker Dam to provide water for a huge aqueduct to the Los Angeles-San Diego metropolis, and the Imperial Weir Dam and All-American Canal to carry water to the vast reaches of the Imperial Valley – and every drop of water through the dams generating electric power for the Southwest. The desert reality was transformed for – well, maybe not forever, but for the life of the dams, ultimately proscribed by the inflow of mud as the busy river continued its mindless task of reducing the Southern Rockies and the Colorado Plateau to sea level peneplains.

But the Bureau did not stop there. After the second World War, under the aegis of the Colorado River Storage Project, the Bureau continued to build big storage dams with canals to carry water out into the high orographic deserts above the canyons and the hot subtropical deserts below the canyons, remaking most of the river – mountain tributaries collected the melted snowpack into rivers, as with all rivers – but then it went into desert ‘distributaries’ distributing the water to vast farms and rapidly growing cities in regions called ‘Death Marches’ by early explorers. That very little freshwater was left to ‘waste’ into the salty ocean was regarded as a victory – until it wasn’t. Another story there.

What we have to confront today, in the Colorado River region (natural basin plus out-of-basin areas served), is the extent to which the engineered new reality is ultimately dragged down and even stalled by the scientist’s dour desert realities the engineers thought could be transcended. It is unfair to blame the Bureau for the apparently unlimited growth of people moving into the river’s region, but the engineer’s ‘Can Do!’ attitude toward that growth has done little until very recently to bring us to confronting the unavoidable collision of unlimited demand on a limited resource – and now, a shrinking resource, given new concerns raised by those relentlessly reality-based scientists.

E.C. LaRue of the USGS warned us back in 1922 that storing the river’s water in big open reservoirs would reduce the supply of available water due to evaporation and bank-storage losses, but that seemed like a reasonable trade for water availability year-round over a river whose three-month flood was mostly lost to the sea anyway. The loss could be written off as ‘surplus’ – until the relentless demand ate up the fictional ‘surplus.’ Now it is suddenly necessary for the Lower Basin to count the ~800,000 acre-feet of evaporation from the Lower Basin reservoirs, canals and fields, as well as their half of the Mexican decree, against their Compact decreed 7.5 million acre-feet. Which they have reluctantly agreed to do – so long as the federal government pays them for not using what was not theirs to use anyway. (money that may be threatened by Mumpty’s DOGE).

And on top of that, there is gradual, general, reluctant acceptance of the fact that the burning of fossil fuels that powers nearly all of our civilization, plus the vast tonnage of cooling concrete that has gone into our great works, plus the gases from an increasingly vicious cycle of expanding wildfires and melting permafrost, are adding gases and heat to our atmosphere that are raising temperatures around the planet and causing changes in the global climate – oops.

I forgot; ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ have been officially eradicated from the public discourse. We are creating another new reality to pile on top of the old new realities we’ve created over the past century plus: We have grown so accustomed to thinking like George Bush’s advisors that we don’t really notice that our newest new reality is just the child’s belief that putting our hands over our eyes will make the real world go away.

So I think that’s what we can do, at least in the Colorado River region: uncover our eyes, and start adjusting our new realities (which are not entirely bad) with the natural realities that still constrain the engineers – as even most of the engineers seem willing to acknowledge. We need to acknowledge that Becky Mitchell’s advice is now counterrevolutionary – ‘We must learn to plan for the river we have, not the river we wish we had.’ To the Trumpty-Mumpties, that’s almost Unamerican, saints be praised.

Whatever we do along those lines, however, it seems necessary that the scientists and engineers work together on it: both acknowledging the wisdom in the scientist looking carefully before the engineers leap – but both also acknowledging that some leaps will be needed….

***

Margaret Chase Smith in 1950:

It is high time we all stopped being tools and victims of totalitarian techniques – techniques that, if continued here unchecked, will surely end what we have come to cherish as the American way of life.

George: I liked your article last week. It deviated slightly away from water, but your concerns seem to be a premonition of things to come. The decision by the Trump Administration to deny Mexico water and accuse them of breaches to the 1944 treaty indicate Trump is not just willing to insert himself into compact operations, but compact operating rules and procedures. We should have seen it coming when he made bizarre decisions regarding CA water during the LA fires. We are in big trouble, and the only thing we know is Trump will not make decisions in the best interests of those who depend on western water resources.

I share your concern that the worst is probably yet to come.

Nice installment, George. Thanks!

And as for ‘We must learn to plan for the river we have, not the river we wish we had”, the river we wish we had is an unattainable dream while the river we actually have is an ever-changing reality.

Cutting funds for fighting climate change – to name but one of the “wish we had Trumpty-Mumpties dreams” – is not facing that reality. It is creating a nightmare. Just one of many yet to come I fear.

Keep us awake, George!

RESPONSE TO EARLIER POST ABOUT SCIENCE VS. ENGINEERING IN COLORADO RIVER REGION:

My dad spent his career working for the Bureau on the following projects: Colorado/Big Thompson, Palisades Dam (Idaho Snake River), Paonia Dam, Marrow Point Dam, Glen Canyon Dam, then off to Nevada replacing a dam on an Indian res and on to central California working on water distribution. As you know, many of these projects are in the Colorado River Basin. Back then, there seemed to be little controversity about this work, now it seems to be a big mess! I enjoy your reporting and your take on all of this.

I think we’re seeing that there are more ways than one to ‘romance the river.’ Through the first two-thirds of the 20th century, we saw America rising to the challenge of controlling and ‘rationalizing’ the river, which was done in a kind of magnificent way by the engineers; but they had ignored some scientific studies of the river that led them to build for a larger river than they had…. But a larger problem was the tendency of humans to look for adventure, romance in their relationship with life (and its rivers), and when their world has mostly been controlled and rationalized, the romance lies in finding and restoring some of its wildness…. Not always with a full awareness and appreciation for their own dependence on the wildness controlled and rationalized….

RESPONSE TO EARLIER POST ABOUT SCIENCE VS. ENGINEERING IN COLORADO RIVER REGION:

Oh my, finally got to this after a bad week of things breaking. And this is a perfect example of things breaking on a scale I could never dream of. It is like folks saying “it always snows,” until it doesn’t. It’s like making the desert bloom until is too hot and dry for even most cacti.

I wish I believed science and engineers could work together. I know scientists would but engineers mostly have a hubris of their own, so I am skeptical. BUT this is a wonderful perspective. I just wish you’d put the Margaret Chase Smith quote in full context. She was one I think the first Republican to stand against Joe McCarthy and with Edward R Murrow helped rally the opposition and all too temporarily stopped the forces of fear.

Thank you a 1000 times my friend