We left the Colorado River a couple months ago to explore the Trumpsters’ effort to use the public lands in the river basin to ‘unleash American energy’ and return us to the glorious age of cheap petroleum – and why it’s not happening. At that time, the seven states in the river’s basin were in a stalemate over a management plan to replace the cobbled together ‘interim’ management guidelines that expire next year. The Trumpsters’ have not interceded noticeably in this situation, since it appears to require complex and sustained thought.

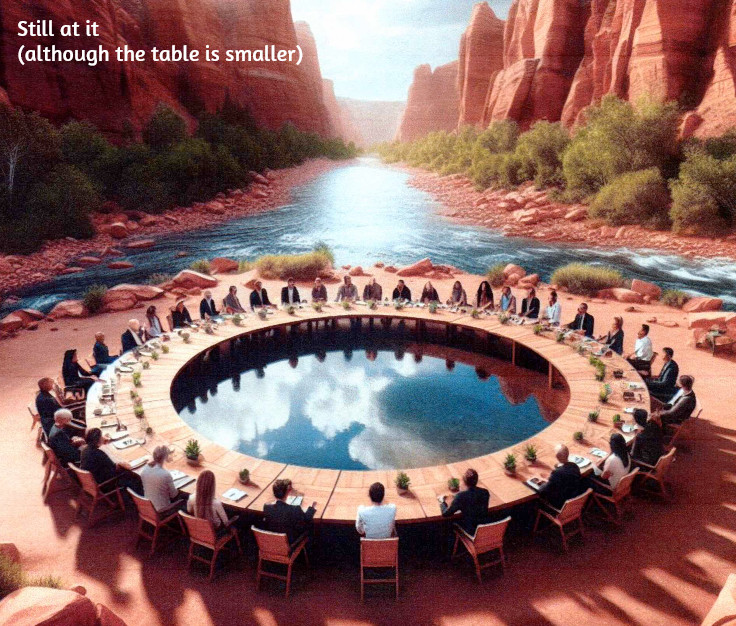

Unfortunately, the stalemate is still the basic situation. As a couple water mavens put it, we’re all still waiting for the black smoke coming out of the chimney to turn white. The Basin’s state representatives are meeting together regularly though, with input from the First People, and reports from the meetings suggest that the participants have all agreed to ‘work with the river we have, not the river we wish we (still) had’ (if we ever actually did have it) – the Colorado River Compact’s river. So a little review here today, to remind us where this puts us….

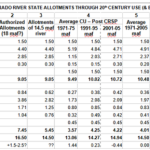

The Colorado River Compact was created in 1922 for a river that had been, for a couple decades, running flows guesstimated to average 18 million acre-feet (maf) annually. The compact commissioners thought they were being conservative in only dividing 15 maf among themselves, and assumed that ‘those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information’ would be dividing up even more water after resolving a share for Mexico and resolution of the Indian rights.

The river then played desert trickster and stopped running those big flows, shortly after Congress passed the Boulder Canyon Act to reconstruct the Colorado River through the subtropical deserts below the canyons. By the end of the 1930s drought that followed, the states’ water leaders knew the numbers in the Compact division might have been for a river that no longer existed, if it ever really had. But they persisted with the Compact, in the spirit of the unnamed quasi-mythical G.W. Bush administration official: ‘We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.’ The next half century was invested in creating our own imperial reality for the Colorado River – until we began to run into more ‘natural’ realities than we’d anticipated….

The unimperial reality today is a river whose annual flow since the turn of the century has dropped to an average around 12.5 million acre-feet (maf), two-thirds the size of the Compact’s river. That is ‘the river we have’ – and we are aware of the extent to which our superimposed imperial reality on the Colorado River region (and on the whole planet) has caused a lot of this unanticipated loss of water.

Exactly what it means when the basin-wide negotiators say they are working with that ‘river we have’ has not been revealed. One bad sign, however, viewing it from ‘outside the box,’ is their persistence in thinking of the river as divided into a four-state Upper Basin and a three-state Lower Basin, a construct destined by a competitive appropriation culture to devolve into chronic conflict – which it has.

Much of the conflict has revolved around the foggily written Article III(d) of the Compact, stating that the Upper Basin ‘will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.’ This could be most rationally interpreted as a warning to the Upper Basin to just be careful to not develop to the point of using more than their 7.5 maf/year (which the four states have not even come close to doing) and cutting into the Lower Basin’s 7.5 maf in dry periods. Or it could be irrationally interpreted as a delivery obligation that the Upper Basin had to deliver regardless of the natural state of the river, even if an extended drought forced the upper states to short themselves in order to deliver the required 7.5 maf.

Given a history of tension among the states based on how fast California was growing, the obvious choice between those interpretations was to believe the worst. Their intent in convening the compact commission had been to prevent a ‘seven-state horse race’ to appropriate water for their futures; they wanted a seven-state division of the use of the river’s water that would override interstate appropriative competition. But they didn’t know enough about either the river or their own fantasy-infused futures to do that desired division. The two-basin division has come to be regarded as a stroke of genius, good for all time, when in fact it was just an expedient measure – one wouldn’t be wrong to call it a ‘desperate measure’ – to cobble together something that would persuade Congress that the states were enough on the same page so Congress could put up the money for a big control structure (Hoover Dam).

But in their haste in pasting together the two-basin compact, they appeared, through Article III(d), to make one basin ‘junior’ to the other, subject to a ‘compact call’ in an extended drought – or at least that is how everyone chose to interpret it. The 2007 ‘Interim Guidelines’ began to address that (perceived) inequity by imposing cuts on the Lower Basin states when Mead and Powell Reservoirs dropped to dangerous levels, but on not the Upper Basin (leaving their shortages up to the erratic river). But interstate ‘seniority’ played a big role in the size of cuts for each Lower Basin state, belying the notion that the Compact would protect states from interstate appropriative competition.

So what could today’s negotiators be doing instead? There is actually a constructive and useful way to divide a desert river into two ‘basins,’ based on the nature of the desert river. All rivers are surface water that is leaving – maybe reluctantly – the land it flows through; it is leaving the land because the land and its life were not able to put the water to use in support of life or to hold it as groundwater in an aquifer. Even much of the groundwater that doesn’t get used by the plants does not escape leaving the land with the river; isotopic analysis indicates that over the course of a year more than half of all the water in surface streams is groundwater trickling back in.

This is not to say that a river is nothing but a drainage ditch – an earlier Army Corps of Engineers perspective that messed up a lot of rivers, trying to make the drainage more efficient by straightening channels. All rivers have a much more complex relationship with the land they are flowing through than just ‘drainage.’ Most rivers have their origins in highlands – mountains or other significant uplands – where steep slopes or fast snowmelts produce too much water to sink into whatever soil there might be; this generates surface flows that become small streams confluing to form larger streams and rivers. Through hyporheic exchange, surface streams either gain groundwater from the land they flow through when that land has a higher water table than the stream level (a gaining stream), or they lose water to the riparian areas along the river when the water table there is lower than the stream level (a losing stream – although, since the water it loses nurtures life in the riparian area, I think hydrologists should consider calling it a ‘giving stream’).

For rivers in humid regions, there is adequate precipitation throughout the river’s basin so the rivers will usually gain more from the land they pass through than they will lose (or ‘give’); they are gaining streams that grow from both surface and ground water until they discharge it all into the seas. But a desert river like the Colorado, on the other hand, is a dependable gaining stream only in its highland headwaters, where the Colorado River accumulates 85-90 percent of its entire water supply from the Southern Rockies, Wind River and Wasatch Mountains above ~8,000 feet elevation. This water-producing region is less than 15 percent of the whole basin. (That ‘division contour’ is more accurately an ‘ecotone,’ a blurry edge zone, in the 7,500-8,500 feet range.)

Below the ~8,000 foot elevation, the river’s tributaries flow first into the high orographic ‘cold deserts’ (steppes) of western Colorado, southwestern Wyoming and eastern Utah. Most of its tributaries have been ‘stepping down’ through the mountain region in a series of canyons alternating with floodplains, all of it the water’s work – and all of it the beautiful erosion and deposition that draws and holds us here. As they drop into the high desert, they get into a serious canyon-cutting project through the Colorado Plateau, up to a mile deep – a mystery story in itself that I’ve written about before. After more than five hundred miles of canyons winding through the Plateau, the river flows out into the subtropical Mojave and Sonora ‘hot deserts,’ and thence – only occasionally now – emptying what’s left into the Gulf of California.

But once they drop out of its headwaters highlands, desert streams and rivers like the Colorado and its tributaries become losing (giving) streams; they get little new precipitation below the ~8,000 foot contour. The occasional exception is the desert cloudburst that manages to penetrate the desert’s heat shield, dumping a huge rain that mostly runs off the desert land in a quick, destructive flood, filling dry arroyos and stream beds for a few dangerous hours. Or a rare winter snowfall that melts and sinks in, activating flora and small fauna that have lain inactive for long periods, instigating pilgrimages from hundreds of miles away just to see the desert in bloom.

The ‘natural’ Colorado River (the river before the 20th century CE) became a ‘big river’ for two or three months a year, in the May-July period when its mountain snowpack released the majority of the river’s water into its tributaries and ground storage. But once the snowpack was gone, the natural river became an increasingly modest flow, fed largely by groundwater, and as it wandered through the desert regions, it gave what water it had to riparian life (a process that intensified as humans began ‘broadening’ its riparian areas through irrigation systems), or into desert aquifers – and a lot of it just evaporated or transpired back into the atmosphere (losses that increased as humans spread more of it out in reservoirs and fields).

There were probably years (like our current water year) in which the last of the natural river’s water never made it through its lush delta to the sea in the autumn. It is not unusual for a desert stream to completely disappear in its desert; some 40 surface streams and rivers flow into the Great Basin, and most of them just disappear after spreading their limited beneficence en route.

The natural and logical ‘two-basin’ division for a desert river like the Colorado, then, would be into a ‘water production region’ and a ‘water consumption region.’ With the exception of mountain mining or resort towns, and the mountain flora and fauna, nearly all the users of Colorado River water live below that ~8,000 foot division. They are all in the same boat, trying to figure out how best to share a ‘losing river’ when its flows drop into the desert regions where they live.

The Colorado River Compact ignores this natural division of the river. The clumsy division into the four-state Upper Basin and three-state Lower Basin is done according to state boundaries, which have no geographic or hydrographic relevance to the Colorado River Basin. The state boundaries also include a lot of heavily developed land outside the natural river basin that can lay claim to Colorado River water as part of the state – and they have population and wealth concentrations that enable them to move that water out of the basin through tunnels. ‘We are an empire, and when we act’ et cetera et cetera.

The Compact division is especially problematic for the Upper Basin. A quarter to a third of the Upper Basin area is the river’s major water production area, scattered among the mountains of the four states above the ~8,000-foot contour, and the rest of the Compact’s Upper Basin is part of the river’s water consumption region. The Compact makes no such distinction, and all the water above the Upper-Lower division point near Lee’s Ferry is presumed to be the Upper Basin’s – minus the annual ‘delivery obligations’ of 7.5 maf for the Lower Basin and half of the 1.5 maf for Mexico. Given that the river’s annual flows vary between 5 and 20 maf, this makes the Upper Basin’s Compact allotment of 7.5 maf annually a fantasy.

Acknowledging the desert nature of the Colorado River suggests a rather radical, but common sense two-basin management strategy for the Colorado River, addressing two main challenges: first, to work out an equitable division among all users for the use of the water that flows into the ‘water consumption region’; and second, for all water consumption region users to collaborate on optimizing (not ‘maximizing’) the flow out of the ‘water production region’ and into the deserts.

And a third challenge (which should be first) would be to transcend (abandon) the Compact’s two-basin division, the artificiality of which just gets in the way of desert-river reality at best, and at worst fosters a competitive rather than collaborative attitude between the two basins.

And that’s enough for today. We will look more closely at those challenges next time – unless the negotiators have come up with a brilliant breakthrough to parse out. Don’t hold your breath….

Humankind cannot bear too much reality.

– T. S. Eliot, Burnt Norton

And while the muckity mucks dawdle and doodle through meeting after meeting and the EPA abandons even a desire to appear to have non-monetary interest in the earth’s well being, the Colorado keeps getting less and less mighty. Bless the Big Red as it takes another hitch in its belt, determined–so it seems–to take one for the non-team. Many years ago, the Texan John Graves wrote a classic about another river, just as you are on the very verge of doing now. Thanks.

How about some quotes from two WILDLY divergent authors that describe the situation?

“You can ignore reality, but you can’t ignore the consequences of ignoring reality.” – Ayn Rand

“The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.” – Flannery O’Connor

Either WOMAN provides good guidance on this issue.

Great history job! And it gets at the central problem rapidly becoming the main existential threat by 2040; that is, the earth has been completely overrun by it’s homo conquerors and Nature no longer can keep up at all in so many ways. ken

Excellent commentary! The so-called “natural flows” concept that gets away from using the 15 maf as a standard no longer attainable is yet to be fleshed out. I have long felt it was the disconnect between states’ water rights, which are limitless, vs. the compact water rights, which are capped, that was the heart of the problem. It was states’ water rights that led to so many out of basin diversions. It is how we wean those out of basin water users off Colorado River water that seems to me the key to bringing sustainability to the river basin

Yes – It’s constitutional: ‘The right to divert shall never be denied’ in Colorado, but under the Compacts Colorado only gets 51.75% of … whatever’s there, and whatever is there, it is never infinite….