In the last posting, I discussed the great volume of written and visual material that has emerged in recent decades about the Colorado River – First River of the Anthropocene – almost all of it increasingly critical of what we have done with and to the river. It is certainly true that a lot of what we have done reflects poor information and poor planning. We have built storage and delivery systems for a river half-again or twice larger than the River actually was – and it is now diminishing steadily from what it was. And what we have done we can only call ‘anthropocentric’ – something we have to cure ourselves of in the Anthropocene – call it now the Conscious Anthropocene. There is, yes, much to criticize – but then we were not really aware yet that we were in the Anthropocene, and that what we did made differences we needed to anticipate.

But lurking behind much of this River literature is the vision of a different river – a beautiful river that we want to believe we remember, a river wild but noble (think of ‘the noble savage’), a beneficent giver of gifts to the lands it meanders through, abundant, sustainable and resilient (there: got my obligatory buzzwords in). That’s a river that exists in our minds, and we call it the Colorado River, the River that we have Ruined. About that river, we tend to be like the old dispersed Israelites: ‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept when we remembered Zion.’

But is that river in our minds really the river that was here when our Euro-American progenitors arrived a couple hundred years ago? On a nice day, maybe; on the 500th consecutive nice day with no precip, maybe not. And not on the days when a hot wind was blowing upriver off the Mohave, or a cold wind was rolling downriver from the Never Summers. Nor when a spring heat wave was bringing the snowmelt down too fast to catch – or a cold spring was keeping the water up in the snowpack. And there was essentially nothing one could do about any of that. Basically the Colorado River the pioneers remembered was not an accommodating river – except when it occasionally was. And the way it usually was led to dreams fed by frustrations that had a lot to do with why it become the First River of the Anthropocene.

Here, for the record, is that River’s story, the River the early comers would remember.

The river’s story began when the current Rocky Mountains were created 80 to 55 million years ago, due to a tectonic push on the North American plate by a Pacific Ocean plate, causing the crust of the land plate to crumple up in the middle like a throw rug might if pushed across a rough floor. This uplifted crumpled chaos was a mix of metamorphic rock, formed by deep pressure and heat, and sedimentary rock, layers of sediment from previous erosions solidified under pressure. Much of the sedimentary rock was recycled sediment from an earlier set of Ancestral Rockies that had been eroded to sea level.

Also pushed up around the same time was the Colorado Plateau, west and south of the mountains, a solid block of thick sandstones, limestones and other sedimentary rock – but rather than crumpling upward like the mountains to the east and north, it rose without much of the fracturing, tilting and even overturning that marked the mountain-building. Why this formative difference? That enigma was compounded by another enigma, north of the Plateau: there the crust of the North American plate was being stretched, thinned, and dropped down between some small stubborn mountain ranges in the range-and-basin geology we know as the Great Basin.

While all of that was still rising, crumpling, or sinking, the solar-powered water and wind went to work on their basic task of eroding it all back down to sea level, and streams and rivers began to form in the normal riverine way – small streams joining to form larger streams – as blocks of rock were slowly carved into peaks and valleys.

Three major tributaries evolved: the Green River collecting its water from the Wind River Range and the east side of the Wasatch Range, mostly in present-day Utah and Wyoming; the Colorado River collecting its water from the Continental Divide and other Colorado highlands; and the San Juan River collecting from the southern San Juans and the highlands of northern New Mexico.

Sometime the erosion process got buried under new earth upheavals and had to start over, but water is patient. Our own Gunnison Basin is a good example of this. After 20-30 million years of carving some river channels westward from the Continental Divide and north from the San Juans, those channels were buried by two episodes of volcanic activity 30-35 million years ago. First was the West Elk Volcano whose eroding ruins are the West Elk Mountains today; its explosion left a deep layer of welded tuff over the emergent Gunnison River basin, into which the patient water began carving new channels and valleys – only to have them covered with another layer of volcanic tuff from a volcano whose ruins today are the La Garita Mountains.

The water went to work again, and would probably have created a steep but broadening valley down into the Montrose area and a confluence with the Uncompahgre River. But as it carved down through the tuff, the Gunnison River lowered itself onto the southern edge of a large intrusive lump of very hard granitic stone. Trapped in its course by then, it had no choice but to continue gnawing its way down through the hard rock, creating the steep, deep and narrow Black Canyon of the Gunnison, and bypassing most of the Uncompahgre Valley (a situation corrected much later at the dawning of the Anthropocene).

For more than 90 percent of their evolution to the present, these headwaters of the Colorado River did not flow to the ocean; they all flowed into a large inland sea in the southeastern part of the Great Basin. Rivers were also flowing off the Colorado Plateau into that lake, in a northeasterly direction. That lake might have reached as far north as the Great Salt Lake, which is itself the remnant of a larger Great Basin inland sea.

What happened next is on the level of mysteries, and continues to generate geomorphic hypotheses: how did the Colorado River cut through the Colorado Plateau rising more than a mile above the river’s bed?

One explanation: Another river formed draining the southwest slopes of the rising Colorado Plateau – the Mojave River, some have called it, flowing down into the Gulf of California. But in its headwaters, it was also cutting back into the still-rising Colorado Plateau – and the rivers running north off the Plateau into the inland sea were also ‘head-cutting’ (eroding upstream) back into the still-rising plateau.

There was also some minor mountain building and volcanic activity working up through fractures in the Plateau itself that dammed up river channels with lava, forming more large lakes that eventually overflowed and eroded the dams, probably creating major erosive floods as the lakes drained.

There does seem to be agreement among most of those trying to explain the mystery, that around 5.5 million years ago, something big happened. In my story, the river headcutting east and north into the Plateau from the southwest began to ‘capture’ the channels of the rivers that were headcutting into the Plateau from the opposite side, and the captured rivers began to flow toward the west/southwest, working with the wind to downcut and create the Grand Canyon through the Colorado Plateau. Eventually the forming river ate deeply and far enough into the Plateau to capture all the Plateau’s north and east flowing tributaries – and finally it captured the inland sea that held the flow of all the tributaries running off the Rockies. Two river systems had ‘backed into each other’ and become one. (Is it worth noting here that our first ‘Big River’ act in controlling the River was a compact dividing it back into two rivers politically?)

Serious canyon-making began then, with all the westward flow from the Southern Rockies pouring into the Plateau canyons. This was undoubtedly aided during the past 2.5 million years by the four interstadial meltdowns of Pleistocene glaciers in the Rockies. These meltdowns occasionally resulted in ice-dams that backed up huge high-altitude lakes, which were eventually released in a flood by further melting, creating new canyons in a matter of weeks or months. Gore Canyon, high in the Colorado River headwaters, may have been created by such an event.

So much debris was eroded out of the mountains and the Plateau by the evolving river that, today, it enters the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts on a leveed platform of debris some 20-40 feet above the surrounding desert land. It carried enough debris to the confluence with the Gulf of California to throw a dike all the way across the Gulf, cutting off a hundred miles of it, which dried up under the desert sun, creating the sub-sea-level Salton Sink. Marshy areas atop the dike bloomed into a lush delta.

From time to time the river, still carrying debris from the ever-enlarging and deepening Plateau canyons, blocked its own flow off the south side of the delta dike into the Gulf, and ran off instead into the Sink, which then became the Salton Sea for a geological moment, until the river again rearranged itself to flow off the south side, at which point the Salton Sea would again dry up and become the Salton Sink. This happened most recently in 1905, with a little human help – an ungated irrigation cut into the river’s levee that the river in flood breached, and all ran down into the Sink. The Southern Pacific Railroad almost bankrupted itself trying to close the breach, finally succeeding in 1907. The Salton Sea has been maintained since by irrigation runoff, and for a time hosted a thriving resort industry. But as the pressure is on to use less water more efficiently, the Sea is shrinking and turning into a toxic waste of concentrated irrigation chemicals surrounded by an equally toxic dustbowl.

The tributaries above the canyon region contribute 80-90 percent of the river’s total water, but numerous tributaries in the canyons themselves – the Dirty Devil, the Little Colorado, Diamond Creek – contribute water from the Plateau’s highlands, and others join the River below the canyons, collecting their waters from other sections of the Colorado Plateau and the Continental Divide highlands of western New Mexico. The Virgin River flows out of southwestern Utah to join the Colorado a little upstream from the location today of Hoover Dam. Farther downstream, near Parker Dam today, the Bill Williams River comes off the lower Coconino Plateau.

And far downstream, only a few miles above the old delta, the Colorado is joined by the Gila River, whose watershed is most of the state of Arizona, parts of western New Mexico and a bit of the Mexican state of Sonora. The Gila and its main tributaries – the Verde, Salt, San Pedro and Santa Cruz Rivers – collect most of their water from the Mogollon Plateau and the mountains of eastern Arizona and western New Mexico, but most of that water is now consumed before the river gets past the Phoenix area.

And that is the Colorado River more or less as it was when humans began to wander into the river’s region over the past eight or ten thousand years. This is just one version of the Colorado River’s creation; whatever the actual facts and sequences of origin might be are buried under the river’s ongoing massive erosive processes. But any of the stories will serve the larger truth: that the Colorado River is an ongoing construction project, with no architect evident. It is a young brawler of a river – five million years of getting its act together is not enough time to finish anything geologically, especially for a river creating a Grand Canyon in its midsection. It’s a desert river, almost all of whose water supply comes from a mountain winter snowpack, which for our grandparents meant a two or three month catch-what-you-can flood that was mostly ‘wasted’ to the ocean, moving a great quantity of dirt with it (except for what it left in your headgate and ditch).

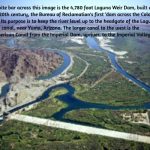

Today, it looks different. It no longer runs a two-month flood of muddy snowmelt water off to the ocean; from the headwaters to the delta, it is captured behind dams, diverted into ditches and canals, run through pipes and turbines, and otherwise harnessed by humans to stand in and push rather than cut and run: the First River of the Anthropocene. But these are all temporary structures with life spans of 500-800 years, on a river for which any time block less than a millennium is a rounding error. And a lot of our structures are paleo-crude; we are not yet a sustainable and enduring presence here, and won’t be until we’ve learned a lot more about water and how it works with and against those who would use it. It’s been said that ‘water is the master, not the servant,’ but that seems to miss an essential point about a free agent that doesn’t work in either-or categories like that at all….

Well, stay tuned. In a couple weeks we’ll look at where the River’s water comes from.