We’re seeing not just being at the table,

but actually having an influence on the agenda.

We’re looking at the next step – because you can have

a seat at the table, but not be taken seriously.

And tribes, especially now in regards to water,

we have to be taken seriously.

– Stephen Roe Lewis, Governor

Gila Indian River Community

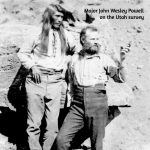

In the last post, I took a closer look at one of the Colorado River Basin’s 30 First People tribes in the Colorado River’s natural basin, the Southern Utes, and the way in which the Ute bands adapted to the civilization that had overrun them. A warrior culture at the time they were overrun and eventually confined to a reservation, they did not take up farming like the Bureau of Indian Affairs trustees wanted them to, although some did engage in cattle and sheep ranching – herding being the least traumatic (agri)cultural transformation from the hunter-forager way of life.

But what really caught the Ute imagination was the idea of taking over the development of their gas and oil reserves, a leap over the usual agricultural transition, right into industrial culture, a competitive field that may have spoken to their residual warrior spirit. They chose, however, to plunge into capital development their way, the ‘Indian way,’ essentially a ‘one for all and all for one’ social capitalism rather than the mainstream’s ‘rugged individualist’ route of private capitalism – enabling them to collectively accumulate wealth from the fat years for the coming lean years.

But what about the other First Peoples in the Colorado River Basin – how have they adapted? Some of the other warrior Peoples retained their lack of enthusiasm for the farming way of life. The Navajo Indian Irrigation Project (NIIP), a system of canals and laterals to irrigate ultimately around 110,000 acres from the Navajo Reservoir on the San Juan River, was begun in the 1960s to facilitate a transition to farming; but when the first allotments of the NIIP land were ready for farming, not very many Navajo were interested. They had come from the far north with herds of sheep, and liked the herding way of life. So what the Navajo leaders decided to do with their irrigated land was to also jump straight to the ‘civilization’ stage. Like the Southern Utes with their fossil fuels, they hired Euro-American consultants and managers to create an agribusiness operation on the reservation, raising food for regional, even national markets as well as themselves. Today, the reservation’s community colleges prepare young Navajos for those management positions in the tribe’s agribusiness, with dividends distributed to the people. Meanwhile many of the Navajo People have individually continued small-scale family herding as their accommodation to agricultural adaptation.

Many of the other desert-based First Peoples, however, were willing to embrace the farming life – but most of them were already farming Peoples long before the Euro-Americans arrived. This is especially true of some of the First Peoples in Arizona – the Basin state most blessed with First Peoples, 23 of the 30 groups. A large number of those tribal groups could actually be called ‘post-civilization’ farmers, especially the ones in the valleys of central Arizona’s Gila and Salt River Basin: groups now known as the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, the Gila River Indian Community, the Ak-Chin Indian Community and the Tohono O’odham Nation. These Peoples all claim descent from the Hohokam (or Huhugam) People, an advanced irrigation culture probably comparable at its peak to the early civilizations of Asia Minor’s Fertile Crescent.

The story of the Hohokam – what we can deduce about it – was probably a classic illustration of the Holocene ‘trauma of success’ cycle: population growth driving a transition from hunter-forager to either warrior cultures fighting over territory and food, or ‘defensive agriculture’ to create defensible food supplies. That transition in turn led to farming surpluses feeding more population growth and forcing them into ever more urbanized and industrialized cultures: the ‘civilization’ stage that eventually, like all civilizations so far, imploded from too much density, complexity, and inequity between managing and working classes.

As best the archaeologists and surviving tribal peoples can estimate, the Hohokam culture probably reached its civilized peak in the 13th and 14th centuries by the European calendar, having spread through the entire Gila River Basin in southern Arizona, with more than 150 miles of canal works good enough to have been cleaned out and reused by early Euro-American settlers, and highly developed towns and cities in the Sonoran Desert with multi-story buildings, probably resulting from cross-fertilization with the master builders of the Ancestral Puebloan civilization in the San Juan River and Mogollon Rim regions. The division of labor to keep everyone busy extended to supporting artists creating beautiful pottery and other ‘high culture’ activities. All accounts of the Hohokam mention their ‘ball courts’; one imagines a kind of ‘professional’ NFL among the Hohokam centers. But by the mid-15th century, barely a century before the Spanish entrada, it all fell apart, probably triggered by a major drought on top of the constant problem of silted canals, and also probably the usual challenges of density, complexity and class inequity.

Groups that survived the conflict, chaos and starvation following the collapse, went back to local community subsidence farming, still irrigating from the Gila River and its tributaries. But within the following century, the European invasion commenced, with the new European diseases moving out ahead of the waves of Second Peoples, clearing out half to three-fourths of the First Peoples who were otherwise in the way of the manifest march of Christian industrial civilization.

Most of the Spanish entrada split around the subtropical Mojave and Sonora deserts, moving up into ‘Alta California’ and into the less forbidding high deserts of the Rio Grande Basin, thus only impacting the Colorado River Basin relatively lightly. But with the end of the War with Mexico, and the Mexican Cession that turned ‘El Norte’ into ‘the American West,’ the pace picked up; the basin became both a highway and stopping-point for gold-rush unsettlers and agrarian settlers.

That was the period when confining the tribal Peoples to reservations began in a serious way in the Colorado River region – get’em outa the way. With the warrior Peoples, the reservations were regarded by both sides as prisons – in 1863 the U.S. Army, angered by the Navajo’s raiding, launched a massive attack on them, burning every village they could find and rounding up the Navajo, putting them on a death march to a barren place in eastern New Mexico far from their adopted homeland. They were prisoners of war, and treated as such, until they were transferred in the late 1860s from care and keeping of the War Department to the new Office of Indian Affairs, and the surviving Navajo were marched back to a piece of their old homeland.

But at that same time – in 1864 – a group of First Peoples who were trying to farm in the floodplain of the Colorado River went to Charles Poston, an Indian agent, and requested that he get the government to create reservations for them. This group, since known collectively as the ‘Colorado River Indian Tribes,’ felt they were going to be pushed out of their homeland by white homesteaders and gold prospectors claiming land and water under laws never really explained to the First People. They were willing to give up their traditional hunting grounds upland from the river if they could be assured that they could continue to have the floodplains for farming. Poston arranged for that, and the People named a village on their reservation for him.

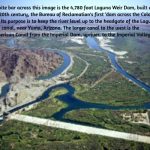

Things did not go entirely smoothly for the Colorado River Indian Tribes, however, after their reservations were created; the BIA started crowding them by moving in portions of other tribes – and during World War II, 17,000 Japanese-Americans were held there as part of the shameful internment policy. The Colorado River Tribes were compensated for all that, however, by getting a weir, Headgate Rock Dam, built across the river to keep water in their canals – both dam and canal being built with Japanese labor during the war. I don’t know whether it is ironic or just interesting to note that one of the few domestic projects built during a time of war production rationing of everything, was a dam for a group of Indians.

But by the time the dust of the Euro-American invasion across the continent had settled after the turn of the 20th century, the First Peoples found themselves – from their perspective – either confined on reservations or protected by the reservation, depending on the life they had lived before the advent of the Second People.

Either way, though, they found themselves with limited or no legal access to essential water, despite the 1908 Supreme Court Winters decision saying they had ‘federal reserved water rights’ dating from the creation date of their reservation. But during the decades before and after that decision, the Euro-Americans had essentially appropriated most of the West’s water for their own agriculture, towns and cities, and industries under Euro-American laws – at a time when the federal policy on the trust responsibility was to ‘civilize the Indians’ through forced cultural assimilation and dispersion from the reservations into the general populace, thus (they hoped) eliminating any reservation water issues.

But by the 1970s, after the American Indian Movement had gained more popular support for the First Peoples than for the government agencies trying to control them, it was clear that forced assimilation was not going to work. The government was faced with the fact that the trust relationship obligated them to help the First Peoples carry out the initial purposes of the reservations.

On the western reservations, this meant getting enough water on the land to nurture ‘civilizing’ agriculture. The federal response to this obligation ran a political spectrum from outright denial of the responsibility (as reflected just this past summer in the Supremes’ decision that the Interior Department had no treaty-specified responsibility for helping the Navajo determine their water rights), to efforts to actually provide water access through projects like the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project – but with no resolution of total reservation water rights. Ambiguity reigned.

Often left to their own devices, the First Peoples knew they could go to court in the wake of the Winters decision and sue for what they believed would be an appropriate quantity of water. But neither the Euro-American courts nor the federal bureaucrats had any appetite for telling other Euro-Americans that they had to give up some or all of their water for the People there first. The court process was usually lengthy, often decades, and tilted toward those already using the water – as the Jicarillo Apaches learned when the court awarded them only a sixth of what they needed. As a Justice Department lawyer put it, ‘When an economy has grown up premised upon the use of Indian waters, the Indians are confronted with the virtual impossibility of having awarded to them the waters of which they have been illegally deprived.’

There was the further fact that the courts would only quantify a water right – ‘paper water,’ useless until systems existed to put it to use. So the First Peoples went to an alternative: to sit down with all involved parties, the feds, the state, the current water users, and work something out – with the lurking threat that, if negotiations didn’t work, then everyone should plan to spend a lot of time and money in court. The People knew they would have to give up some of the water they deserved, but would hope to get out of the process some help in developing what water they could get. The ‘bird in hand’ strategy: an acre-foot of ‘wet water’ running to a field is better than two acre-feet of ‘paper water’ in the courthouse.

The settlement process began in the 1970s; by the 1990s, the Interior Department had made it a formalized process, and encouraged it over going to court. Congressional approval of most settlements is required, especially when appropriations are involved for new physical structures or payouts to Second-People farmers or communities who lost water to the tribal Peoples in a settlement. Some of the costs are to be shared by the states, individuals and tribes involved, and the cost of a settlement to the government is supposed to be no greater than a reasonable estimate of the cost of adjudication if it went to the courts.

To date, Colorado River Basin First Peoples have worked through 14 different water rights settlements, most of them in the Gila-Salt-Verde River Basin; the settlements range in size and expense from 1,550 acre-feet of water for the Yavapai-Prescott People near the Verde River with total settlement costs of $200,000, to 653,500 acre-feet for the Gila River Indian Community (including most of Southern Arizona’s Tonono O’odham Nation) at a settlement cost of more than $2 billion. For those interested in pursuing this in more depth, the Congressional Research Service has a good report on ‘Indian Water Rights Settlements.’

What most interests me, however, is how ‘civilized’ this process appears to be: to realize there’s not enough water for everyone to get all they would like, but rather than deciding it on the basis of ‘I was here first,’ or ‘my use is more important than your use’ – let those things be said, but then go on to figure out how to equitably make do with what you all have. Maybe with some new structures, maybe some new efficiencies, maybe general conservation, maybe paying for some water now to avoid paying a lawyer later. But at the end of it all, there’s a settlement that works somewhat for all parties for at least the time being. It seems too simplistic to call such settlements ‘win-win’; a durable settlement will be one in which the parties feel their losses do not exceed by too much what they’ve gained. And that may be as good as it’s going to get in the Anthropocene.

Teresa Pijoan, a Pueblo-raised Indian story-teller, told me years ago that most stories of the First Peoples end with a sense of balance either created or restored. Stories of the Second People, on the other hand, tend to end in a win for the good guys; if they don’t, the story is a tragedy. The seven basin states – each its own idea of ‘the good guys’ – have a history of working for the win; the current efforts to negotiate a new or modified management scheme for post-2026 already have opening positions promising to ‘focus on making our own state stronger’ (Colorado water leader). With the river already reduced by a third from the good old days of the Colorado River Compact, no state is likely to come out ‘stronger’; but we might all come out better (if only ‘better people’) if we work from a whole-river perspective, to balance equitably the losses inevitable in facing Anthropocene realities. I think we need the First People at that table; they already understand negotiation in a harsh environment.

Next post – probably a look at how the ‘2026 project’ is, or isn’t, shaping up, and some unsolicited thoughts that are probably not going to happen, given ‘the way we do things,’ otherwise known as ‘Western Civilization’.….

Wow, a long needed deeper dive into one of OUR genocides and open air prison systems. We got there before Israel. This hurts to read but I HOPE everyone does.

Excellent, George. If I’d had time – and a lot more knowledge of how it all worked on the ground – when I was teaching American history, this is the sort of thing I’d have incorporated, even if only briefly, into our treatment of the 19th (and now, 20th) century settlement of the west. Of course suggesting to white suburban students that perhaps the provisions of some treaties, and even the treaties themselves, might not have been very “fair” or “just” might well put me into hot water with local MAGA parents and school board members nowadays. As it is, I’m pretty sure that this is the sort of thing that isn’t mentioned in most standard American history textbooks – it certainly wasn’t mentioned in any of the texts my district issued to my students a generation ago.

Having just finished Killers of the Flower Moon, this paragraph really stuck out to me “They had come from the far north with herds of sheep…………they hired Euro-American consultants and managers to create an agribusiness operation on the reservation.”

I think this was one of your best pieces of writing especially your conclusion.

Very interesting. The “First People” have a lot of good ideas and thoughts still floating inside from the pre-civilized stint in the new world after their first half millenium as hunter gatherers in various part of the world after Africa. In future (near future) we shall need to hear and heed some of them. The whole idea is in line with the idea that, in order for the species to survive at all, we will have to return to a form of civilization that remains quite small. This requires new forms of society with villages, towns and a few cities as well some form of social capitalism. ken

Always thought provoking and insightful. The past truly is prologue.