Presented in April 2016 at the Gunnison Arts Center, as the opening for a writer’s workshop.

Thanks, David – and thanks for the invitation to be here tonight. Greetings to all of you, and welcome to Western. It has been wonderful to watch David and Mark Todd and other Western faculty bring “Writing the Rockies” from a small summer gathering of western writers, to a focus event for a fullfledged MFA program that helps enlarge our collective sense of the American West in the larger American experience, even as it is developing individual skills and capacities for articulating this mountain west in which we find ourselves – or, speaking for myself, keep working to find ourselves.

My assignment tonight, as I understand it, is to try to tell you, as a fellow writer who’s been here for a while, something about where you really are, when you are here at Western in the Upper Gunnison River Valley – real places in a fragmented abstraction called Colorado, in an even larger and more fragmented abstraction called the United States of America.

Is that important – to know something about where you really are here? You are writers, poets, but some of you would say you aren’t here for a lot of sentimental “sense of place” stuff; you’re here to learn the bottom-line tools and tricks of the trade – how to get into print.

But – on the other hand, you have come all the way to one of the harder places in America to get to, especially if you tried to fly here; there are lots of easier and more accessible places to learn the arcane arts of getting published. We are all doing this here, in the Southern Rocky Mountains, and we are here for “Writing the Rockies.” So – where, actually, are we?

A place to begin is to look first at where we are not. I want to begin with a look at the map of a nonplace called Colorado. If we were in a classroom now, I would be flipping on the projector and flipping off the lights and moving into the flipping ubiquitous powerpoint. But you are all here as poets and writers; visualizing is part of your business. And this is really easy visualizing: look, in the eye of your mind, at the map of Colorado. What we are seeing is an absurdly simplistic rectangle imposed over some of the most diversely complex geography on the planet. Myself, I visualize that map as a blanket draped over a fence, covering more than it shows.

Within those rectangular lines, meaningful only to ships at sea, are at least five very distinct places, each with its own ecology and culture. The Colorado Humanities Council some time ago defined and described ‘Five Colorados’ as distinct cultural entities; I’m thinking along similar lines, but with some variations.

The eastern third of the State is the High Plains, a drier continuation of the Great Plains that stretch all the way from the Mississippi River – big-farm country with a residual agrarian culture that’s being overrun by agribusiness. The cultural affinity of that part of Colorado is the Midwest.

On the other side of the state – the westernmost part of the rectangle, including the San Juan Basin on the southern edge, is part of the high orographic desert of the Colorado Plateau – a canyon-cut steppe-desert where Indian and Mormon cultures coexist, with large spaces between.

And the southeastern quadrant of the state, the Rio Grande Basin and the Arkansas Basin south of the river, is high desert seguing into the subtropical deserts, a region whose cultural compass has been pointed toward Old and New Mexico much longer than there has been a Colorado or United States.

Those three places misnamed Colorado are all culturally bonded to the larger ecologies and economies from which they have been artificially sliced by the abstract Colorado boundaries; they are only bonded together as Colorado by enforced state governance – and also through highly ambiguous relationships with a fourth Colorado: the metropolitan cluster of growing cities and suburbs along the edge of the mountains that we tend to call Denver Colorado, a city related to both mountains and plains in the same way a port city is related to the ocean.

Four out of every five people who call themselves Coloradans live in that growing metro complex, and the other one-in-five of us have a serious love-hate relationship with it: we love the Broncos and Rockies the cities support, and we all continue to have an embarrassing near-total dependency on the trucks that roll out from the city on schedule to bring us almost everything we need to live in the rest of that abstract state. But we also all fear the needs and demands of the cities, especially for water.

But if you are watching the map in your mind carefully, you know there is yet another Colorado – here, the mountain part of the state, Colorado above 6,000 feet elevation – to me at any rate, the true Colorado, the place where Colorado began as a state of mind before it was ever an abstract rectangle on a map. This is the Colorado you have come to here.

You may have come to this Colorado thinking you were coming to some place in the middle of nowhere. But where you are here is actually the middle of everywhere, everything, at least for the southwestern quadrant of that larger abstraction called the United States of America. Where you are is where the water starts for that whole quadrant, streams becoming rivers flowing in all directions out of these mountains; and where the water starts is where life starts, where everything starts, and what more could a poet or writer ask than the chance to be at the beginning of everything?

So now we will look more closely, deeply at this Colorado, which is a real place, not an abstraction on a map. And I will start with a piece of advice from David Wagoner, one of my favorite western poets:

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you

Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger,

Must ask permission to know it and be known.

So as writers in the Rockies, how do we approach this powerful stranger, this Colorado, to know it as poets and writers? A place to begin is to understand the name itself, Colorado. It’s a Spanish adjective, not a noun, which makes it a little odd for the name of a place. But it is also generally mistranslated. Ask any Coloradan today how it translates to English, and they will probably say – red. Colorado means red. But isn’t rojo ‘red’? Yes – but so what, so is colorado, everyone says so.

But dig into ‘colorado’ a little, with a spoon and not a steam shovel, and you find a much more linguistically obvious and expansive meaning. In an internet discussion on the topic of colorado’s meaning, one person drew on the authority of the Spanish Royal Academy Dictionary to declare that “red or reddish is just a secondary meaning of colorado. As the word’s root itself suggests, colorado means, primarily, ‘having color’, any color.’ Colorful, full of color.

So what, then, is the color of our mountain Colorado? To just begin to answer that, you need to go back to at least a year before the rectangular Colorado Territory was conceived, back to 1859 when the crazy Americans known as prospectors were swarming up every stream in the Upper South Platte River Basin, all the way across the Great Divide to our West Slope valleys, swirling gravel in their flat round pans until they came to a place where what swirled in the pan “showed color” – and that color of course wasn’t red; it was gold. Gold and eventually silver were the original colors infusing the state of mind that drove otherwise intelligent men and women to leave their old lives behind and swarm up the wild rivers and streams of this our Colorado.

We know that even then Colorado colorado, colorful Colorado, had many other colors – the reds, blues and shadows of the mountains, often capped in white, the vast textured slopes of dark green conifer forest and light green aspen forest, the high meadows with their paisley carpets of flowers, the lower gray-green meadows dropping down to soft green floodplains, laced by the meandering rivers seasonally running from clear green-brown to muddy red, fed by the whitewater creeks.

All those colors eventually infused other visions of Colorado in the minds of humans. But in the beginning, in that first basement epoch of Colorado as a state of mind, Colorado’s other colors were not just ignored, they were in the way. Whole hills were washed away in hydraulic mining; forests that weren’t cut down for boomtown lumber were burned to expose rock outcrops; dredges literally plowed rich green floodplains into intestinal coils of sterile gray rubble. Streams and rivers occasionally still change color with runoff from the mines. The first colors, the gold and silver, all disappeared into Denver banks and mansions; the gray-brown mess lingers on here into the present.

The other remaining legacy to mountain Colorado from the miners who were here first was the names; most of the names on our map of headwaters Colorado come from that era – several categories of names. Least interesting are the mundane duh-obvious names – all those Brush Creeks and Clear Creeks and Bald Mountains.

There are the obligatory honorific names like Gunnison River, named for Captain John Gunnison who led the first official expedition through here; there are all the Mt. Garfields and Mt. Emmons named for presidents and governors; there are mountains named for native peoples otherwise generally badly treated, Ouray Peak, Chipeta Falls, Ute Mountain.

There is a whole category of what I think of as the homesick names: Ohio Creek, Virginia Peak, Missouri Flats.

There are also lots of names that are actually drawn from the miners’ own experiences in pursuit of their golden dream: Mineral Point, Ruby Range, Treasury Peak, Silver Creek, Quartz Creek. Oh-be-joyful Creek is a less obvious member of this name-group, but it is probably evocative of the feeling that swept over many a prospector as he panned into a patch of gravel showing color.

But there is something a little – biblical about all of those names: Adam charged by god, to go name everything, and thereby have dominion over it all. This is not the poet coming into the land; it is Beowulf, John Wayne riding over the Rockies, not writing them. But there are some other categories of names that are more reflective in one way or another – names that bespeak some degree of sensitivity to the possible presence of powerful strangers where one found oneself.

There were, for example, literary references in the naming of places – a dumpy little mining town named Ophir, after a fabulous biblical port city; another town named Ilium, the Roman name for Troy. Paonia, a slight misspelling of the Latin name for the peony flower. The City of Montrose just downvalley, named for the title character in Sir Walter Scott’s Legend of Montrose. This suggests people educated enough to know their own history – perhaps even to see how they were repeating it.

Some of those who came also stood still long enough to hear and adopt the names given to places here by people who had lived here for centuries. Names like Curecanti, Cochetopa, Tomichi. Here’s our professor and resident poet Mark Todd on “Tomichi Creek”, where he lives:

Tumit Che: words in Ute

that mean “mountain stream.”

It’s the headwater-trickle

through tundra, a cascade,

a passage that wears rock

with time and flow.

It’s the liquid rush cobbling

pebbles into the bed

of a creek, and the scrawl

of horns and oxbows

to cross a narrow plain

shouldered by hills.

These days we say “Tomichi,”

affixed to roads, signs.

even storefront names,

but somehow too distant

from the water or land

Tumit Che names more,

more than store or sign.

Through tundra, stream,

rock and plain,

Tumit Che names this place,

its sense, and more –

our belonging.

That is the poet coming to Here and stopping, looking and listening – a key to getting permission to know a place. And to be in turn worthy of being known in it.

But that earliest period of this particular Colorado colorado as a state of mind – I think of it as the Fool’s Gold period – was marked by another trace of name-giving that struck me as slim and erratic evidence that some of those fortune hunters who came here had enough of the soul of the poet to see beyond, and even laugh about, their own mundane folly in looking for the Fool’s Gold. These were names for places that reflected what I think of as deep irony – call it the “Poverty Gulch” phenomenon. “Poverty Gulch” is the name of a silver-mining site up the Slate River from Crested Butte. I was once part-owner of an 1890 patented mining claim upvalley here named the ‘No Hope No. 3’. The No Hope No. 3 was apparently accurately named – and probably preceded by the No Hopes 1 & 2.

But Poverty Gulch had the Augusta Mine, a pretty rich mine, relatively speaking – so why Poverty Gulch? What was the state of mind behind those sort of depressed names, found here and there throughout the mining districts? I can think of a couple possible explanations. Easiest explanation: put on the poor face, and you won’t have such a crowded neighborhood.

But second explanation – and this is tenuous: many of the individuals who came to the Rockies on the pretext of looking for gold – something most of them knew absolutely nothing about – were probably at least borderline crazy. Most of them were urbanites terminally tired of being industrialized; many of them were pretty well educated, and self-reflective enough to know that what they were doing was borderline crazy. For this stony mudhole place where you’re harboring this ridiculous hope that it will somehow make you fabulously wealthy – if you aren’t going to name it after the fabulous Troy, with a chuckle, what better name than Poverty Gulch?

We should note that Colorado rhymes with ‘Eldorado,’ the fabulous city of gold supposedly richer than the already pillaged cities of Mexico and Peru. And somewhere in these parts, north of Mexico, were supposed to be the equally fabulous Seven Cities of Cibola. The Spanish-Americans had come armed with sword and cross on the assumption that these golden cities actually existed, to be conquered and plundered in the name of god and king. The more democratic Anglo-Americans, on the other hand, came a couple centuries later armed with shovels and picks, axes and saws, as if assuming that the Seven Cities were a do-it-yourself project, with fabulous wealth for those who got in on the ground floor.

But the very vagueness of those Eldorados may have been their best selling point, and the state of mind of those who came may have been infused mostly by the vague hope that life here would be somehow better, richer, or at least more interesting than what they were leaving behind, ‘back in the States,’ as they used to say, as though the west were another country. And the more vague the vision they followed, the better it weathered the hard rains of reality; people kept coming, knowing only that they were looking for something they didn’t have where they were coming from.

To make a sudden leap to the present, no one has really ever found more than a thinly gold-plated El Dorado in this, the true Colorado. The other colors of our Colorado have nourished other material visions – the cattle operations in the high green meadows and floodplains, the darker green forests harvested for lumber, the snow used for skiing before becoming water, the whitewater streams for rafting and fishing between irrigation headgates, the mountains themselves in all their colors are the foundation for industrial tourism in colorful Colorado. There have been brief bonanzas, but always followed by borrascos – mine-country idiom for ‘busts’. It is possible now to live here comfortably, but it’s best to keep expectations modest. Small fortunes have been taken out of the mountains, but for the most part the old Poverty Gulch saying remains accurate: the way to make a small fortune in the mountains is to come here with a large one.

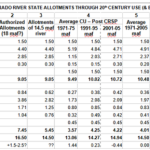

Here in this valley, for example. We’ve just done an exhaustive economic analysis as part of another exploration into economic development opportunities, optimistically called the ‘One Valley Prosperity Project.’ I’m not going into the detailed statistics from that analysis, in comparison to overall Colorado and national economic statistics, but in summary we could say that ‘Poverty Gulch’ is not an inaccurate description for our low-income, high-cost local economy.

Yet we continue to come here, stay here, live here, and most of us do not feel as though our lives here are poor, even though our personal stats may not look that good in comparison to those of America in general today.

But at this point in the relentless evolution of America’s massive industrial experiment, that comparison needs to be balanced against the probability that the future of America in general does not look that good in comparison to today either. Looming problems of climate change impacts, decayed infrastructure, escalating debt, expanding economic inequality, shrinking economic opportunities, political polarization, diminished cultural vitality, and so on is resulting in projections like that of economist Robert Gordon in ‘The Rise and Fall of American Growth.’ Gordon argues pretty convincingly that generations to come will not have better material lives than their parent generations.

So places like this, where people have less than the general cultural expectations, but are still reasonably happy with their lives, may be ahead of the game instead of behind it. Ed Abbey said somewhere that the real challenge is to learn how to have a rich life without needing a lot of money. That is arguably a discipline that we’ve been honing in the true Colorado for generations now.

But it may be that I am just weaving an elaborate hypothesis to cover what is just a hope – that the borderline craziness that brought me here, and has more or less kept me here, is a cultural thing and not just something wrong with me. What was the state of mind that led people – mostly single men at first, but single women too, and eventually families and groups of friends, and even immigrants from Europe and farther, to this relatively hard place of impossible implacable mountains and lovely but isolating valleys, way out on the fragile margin of civilization as we know it?

That’s a question one of Colorado’s greatest poets asks better than I – Belle Turnbull, a trans-planted easterner, a woman who graduated from Vassar, but who ended her life happily with a longtime female companion in a rough cabin near Breckenridge. This is a poem she called “Mountain-Mad”:

Mountains cast spells on me –

Why, because of the way

Earth-heaps lie, should I be

Choked by joy mysteriously;

Stilled or drunken-gay?

Why should a brown hill-trail

Tug at my feet to go?

Why should a boggy swale

Tune my heart to a nameless tale

Mountain marshes know?

Timberline, and the trees

Wind-whipped, and the sand between –

Why am I mad for these?

What dim thirst do they appease?

What filmed sense brush clean?

To just have stood still, stopped, looked and listened long enough to be able to ask the real question so well as that, may be answer enough for the mendicant questioner.

But “mendicant” – that reminds me of another place name here in the “Poverty Gulch” category – “Mendicant Ridge,” a stony extension of Black Mesa west of here, and north of the Gunnison River canyons. But “Mendicant Ridge” has a different feel than “Poverty Gulch.” For one thing, a ridge puts one “up on,” as opposed to a gulch which is “down in”; one can see farther, see more from up on than from down in. But there’s also the fact that “mendicants” represent a special category of “poverty.” Mendicants are poor by choice, accepting Ed Abbey’s challenge, seeking whatever richness of life can be found beyond the material, metallic standard.

Which brings me back, finally, to us poets and writers. I’m probably not giving away any dread secret in suggesting that, if you are here looking to get materially rich as a poet and writer, your odds are about the same as those of the 1860s gold seekers. But if you are here in the spirit suggested by David Wagoner, seeing Here as a powerful stranger, and interested in asking to know it, and in turn be known – well, that brings me, finally to Grendel. A reasonable standin for the powerful stranger.

Grendel, remember, played the fall guy to Beowulf, the earliest Anglo-Saxon superhero in the epic poem of same name. In that epic tale, Grendel was the monstrous epitomy of the dark, unfriendly and sometimes demonic side of the natural world – the mute and arational wildness that we perceived had to be destroyed in order for our way of life to prevail. And for 11 or 12 hundred years after the first tellings in early England, that was our epic: our ever more powerful Beowulf destroying the increasingly diminished Grendel in his wildness. The devastations the early gold-seekers wrought on Colorado’s mountains and valleys was just a late chapter; if Donald Trump and his platform prevail, we will be tearing another arm off of Grendel in the dig for coal and gas.

But 11 or 12 hundred years after that poem was written – with the wildness of the world well tamed, conquered and in many places destroyed by our Beowulfs – novelist John Gardner retold the legend from the monster’s point of view, a neat switch in which an articulate, if seriously confused and conflicted, Grendel watches with growing concern the advance into his wildlands of the human settlements. His best efforts at mass murder and eating his mistakes do nothing to staunch the tide.

But in Gardner’s more or less empathetic retelling of the legend, Grendel makes some interesting observations about the humans and the organization of their society. He sees them as a kind of formless amoebic blob until they are called together and inspired – not by their king Hrothgar, not by the lone-ranger superhero Beowulf, but by their storyteller and singer, whom Grendel calls “The Shaper.” The Shaper sings to Hrothgar’s humans and tells them stories – not even true stories, Grendel notes with outrage – and under his influence the humans are shaped into a people, capable of much more than the hapless individuals.

He says of The Shaper, with both admiration and anger: “He looks strange-eyed at the mindless world, and turns dry sticks to gold.” What is it, to “look strange-eyed at the mindless world”? I think it’s a poetic discipline that begins, only begins, with coming to a place like this mountain valley with no real expectation other than that life here will not be like the life you left behind – and once here, to stand still, as Wagoner suggests, to stop, look and listen, and when you see the powerful stranger, or whatever shadow of it our superheroes have left of it here – to seek permission to know it, rather than to tear off an arm or a leg, to see it strange-eyed enough to turn its dry sticks to a truer and more enduring richness than Beowulf ever leaves behind.

And how do we do this? “How am I to tell you?” asks Belle Turnbull, in another poem that I will close with – sneakily leaving the question more or less unanswered.

How am I to tell you?

I saw a bluebird

A bluebird incandescent

Flying up the pass

And where the wind came over,

The Great Divide came over,

Invisible and mighty,

He struck a wall of glass.

I saw his bright wings churning,

I saw him stand in heaven,

The bird’s power, the wind’s power

Miraculously hold.

Now I will tell you,

Dare my soul to say it,

Speak the name of Beauty,

Accurate and cold.

Welcome, then, to the true Colorado, to the place where the water starts, where life starts and powerful strangers still lurk, and where else would the mendicant poet and writer want to be?