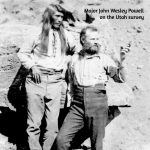

That’s me in the picture, looking at the Missouri River, which Maryo and I encountered on a meandering journey home to Colorado from Wisconsin. Our meanders took us down through Missouri in search of the story behind a small village named ‘Sibley’ on that river. What we found was another George Sibley, the gentleman in the inset image: an early 19th century George Sibley who – working with the Missouri River and what it ran through – played a significant role in opening up the trans-Mississippi West.

I’ve since looked into the life and times of that George Sibley. I’ve learned, among other things, that we are not directly related, but we branch off from a common ancestor: John Sibley, who came to America with an advance party of Puritans in 1629, to ‘make straight in the wilderness the way’ for the 11 ships and 1,000 Puritans John Winthrop led to ‘New England’ in 1630. John Sibley had four sons and five daughters; a 20th-century Sibley compiled a thorough patrilineal genealogy of the sons, from which I learned that I am in the 11th generation from that John Sibley; the other George Sibley in the picture was in the 6th generation, on another limb of what has become a great spreading genealogical tree. There are more than 50 other George Sibleys scattered around on that tree.

But none of us might be as interesting as the George Sibley we ‘encountered’ on a high bluff overlooking the Missouri River that day, where he had arrived in 1808 to oversee the construction of America’s farthest west official outpost at that time, Fort Osage, in the heart of lands long inhabited by the Osage Indians.

To provide some necessary context: in 1800, the Euro-Americans in the newly constituted United States were still trying to figure out what they wanted America to be when it grew up. The dominant culture was pretty clearly the Industrial Revolution, imported from England and Europe. But there was a significant minority of anti-industrialists who advocated for a somewhat nostalgic vision of a decentralized landscape of farming communities, locally sufficient, filled with free men and women, and no more centralized governance than what was necessary to maintain roads and postal service – an Agrarian Counterrevolution.

A chief advocate for the Counterrevolution was Thomas Jefferson. Observing that in England and Europe ‘manufacture must be resorted to of necessity not of choice, to support the surplus of their people,’ he argued that ‘those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God,’ and he wanted America to have an abundance of ‘land to labour’ as an antidote to a ‘surplus of people’ forced into industrial labor.

Thus when he became president in 1801, he put the nation’s money behind his vision; in order to insure an abundance of ‘land to labor’ for the foreseeable future, he purchased all the French claims on the continent below Canada in 1803 – a vast territory that included most of the western half of the Mississippi River Basin and all of the Missouri River Basin.

The Missouri is a beautiful but shallow and dangerous river, prone to early summer flooding from its snowmelt origins in the Northern Rockies (even now that it has several mainstem dams). With loads of mud, brush and trees washing down in ever-shifting obstacle courses of sandbars and snags, the Missouri was often only marginally navigable. Until the advent of steamboats in the 1820s, the shallow-draught keelboat was the principal conveyance, either pushed upriver by teams of polers pushing long poles into the riverbed or pulled upriver by the same teams on ropes.

But after Merriwether Lewis and William Clark led their Corps of Discovery all the way from St. Louis up the 2,300-mile river, and on across the mountains to the Columbia River Basin and the ocean, the Missouri became the principal route west for the romance of Manifest Destiny. In 1825, 150 miles up the river, the Santa Fe Trail took off to the west southwest, part of which also became the southern route to the goldfields of California. The Mormons, the California 49ers and the Oregon parties all followed the Missouri up to its confluence with the Platte River, then followed the North Platte to South Pass on the Continental Divide, and down to where the California and Oregon Trails diverged in the Great Basin. And when the gold, silver and copper strikes were made in Montana and Idaho, the Missouri was the route all the way to its headwaters.

We like to think of this as a process of ‘settling’ the continent, but truly, it was more a process of unsettlement, as the Euro-American invasion rolled over indigenous peoples who had lived in their places for generations, if not millennia. Essentially, everyone everywhere was in some stage of the ‘trauma of success’ – the relentless population increases as the dry cold Pleistocene climate mellowed into the warmer Holocene. Too much success as a species puts the species out of balance in its ecosystem. Hunter-forager peoples who could not expand their territories to bring their numbers back in balance with the rest of the ecosystem, instead adapted by figuring out how to concentrate their food supply in a defensible place – in a word, replacing the forager culture with agriculture.

That was an imperfect solution, however, because it didn’t address the core problem which was uncontrolled population growth; the people kept coming, through birth or migration, until the agricultural community no longer had ‘land to labor’ for everyone who needed it. At that point, new cultural systems had to evolve – denser socioeconomic organization, division of labor, wage labor, class divisions of managers and managed, etcetera – in another word, ‘civilization.’ And civilizations could only continue to support their growing population through expanding their resource base – conquest or colonization of other people and their resources in the ‘swarming’ mode.

Most of the native peoples in North America were, in the 17th and 18th centuries, somewhere between mourning the loss of the hunter-forager culture and adapting to the demands of agriculture, with a few in favored environments descending into the organizational rigors of civilization; some civilizations, like the Cahokia mound-builders, had already collapsed as civilizations tended to do, from continued population growth and inability to manage increasing socioeconomic complexity, and had slipped back into some combination of farming and foraging.

In addition to those internal and inter-tribal challenges, the indigenous peoples were increasingly being pushed by the invading Anglo-Europeans, a swarming civilization that had exhausted its own resources and had moved into the conquest-and-colonize phase on an unprecedented global level. Indian nations trying to work out their own crowding issues were being crowded by other nations being pushed westward by the advancing Euro-American invasion, increasing the level of intergroup conflict. Many of the nations had also been severely impacted by smallpox and other germs that spread in a wave ahead of the Euro-Americans and eventually took, by some estimates, up to 90 percent of a pre-Columbian indigenous population of around 20 million before herd immunity was attained.

That is the West that the earlier George Sibley found himself in following Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase – and threw himself into vigorously. His father John Sibley, a friend of Jefferson, had been appointed Indian Agent for the south-eastern part of the Mississippi Basin; George followed him to Natchidoches, and used his father’s connections to get himself appointed to a ‘factory’ job near St. Louis.

A factory, at that time, was not what we think of today; it was a government trading post for engaging the indigenous peoples. In an economic sense, trading posts with the natives, private or government, were just a pipeline for the Industrial Revolution, funneling furs and hides to the fashion industries of England and Europe. But Jefferson, concerned about some level of fairness to the natives who were losing most of their land to the white tide rolling over them, wanted to create economic interactions that would help ‘civilize’ the natives. Jefferson naively believed that once the natives saw the manifold blessings of civilization, they would want to become civilized themselves. He said of the often chaotic relationship between the natives and the invading Euro-Americans, ‘While they [the natives] are learning to do better on less land, and our increasing numbers will be calling for more land, a coincidence of interests will be produced between those who have land to spare, and want other necessaries, and those who have such necessaries to spare, and want land.’

The factory he was first employed at, in Fort Belle Fontaine just outside St. Louis, closed in 1807, for the reason that there were no more beaver or Indians willing to trek all the way to St. Louis from where there were still beaver. William Clark, Indian Agent and then territorial governor for the land west of the Mississippi, decided to open a new factory at the first fort to be built up the Missouri, in the heart of the Osage Indian nation. And he chose George Sibley to run it.

Thus Sibley found himself in the fall of 1808 working with an infantry company 150 miles upriver from St. Louis, trying to build a fort before winter descended, and also getting to know the Osage Indians and their issues. To run such a factory, charged with civilizing its patrons in the process of bargaining with them, required a ‘factor’ with a unique set of qualities: someone inured to the rigors and privations of frontier life but not roughened and made ‘uncivilized’ by the experience; someone with some level of education and good social skills, and the diplomatic skills to convince others of something uncomfortable or even unjust; and a good bookkeeper to boot. The modest pay and rough living required someone living for more than just wages and security, someone ‘seeking a newer world,’ as Sibley put it in one of his letters. A romantic soul, in other words, as we’ve been discussing in these posts.

Sibley managed to meet all those criteria. The natives came to his factory in good numbers, so long as the beavers, buffalo and deer were still abundant – and not just the Osage. One visitor to the fort noted that there were several thousand Indians camped around the fort: ‘This place appears to be the general rendezvous of all the Missouri Indians, whose continual jars keep the commandant on the alert. Osage, Ottas, Mahas, Pawnees, Kansas, Missouri, Sioux, Sac, Fox, Ioway, all mingle together here, and serve to render this quarter a most discordant portion of the continent.’

Considering that, on the one hand, he was arming the Indians with knives, rifles and ammunition in exchange for their fur, and on the other hand, talking them into treaties – four of them, from 1808 to 1825 – that gradually stripped them of all their Missouri Basin land in exchange for a few thousand dollars, and (final treaty) a reservation in Kansas, this undoubtedly gave Sibley some nighttime thoughts, as noted in his journal: ‘Our camp is now Surrounded by Indians who, though friendly, might notwithstanding be tempted by the prospect of getting possession of the Factory Goods & other Stores, to commit some violent outrage…. There is Strong Reasons for us to be on the alert and Ready at all times for an Alarm.’

The fort and factory were shut down at the beginning of the War of 1812 to get the troops back to the action along the Mississippi. Sibley returned to St. Louis for the duration of the war, and while there, met, courted and married Mary Easton, who accompanied him back to Fort Osage and the factory after the war in 1815; he ran the factory until 1822, when the entire factory system was shut down, mostly due to complaints from the private fur companies who didn’t like the government competition. But the resource was being exhausted too – at a more rapid pace, with the Indians using more powerful weapons. Sibley purchased the factory’s inventory and he and Mary tried to keep a store going, in what became the village of Sibley.

In 1825, however, a new opportunity came knocking. He was invited to lead an expedition to survey the Santa Fe Trail, beginning at Fort Osage. He was not a surveyor himself, but the job also entailed negotiating with Indians along the route, to allow passage to those who stayed on the trail and didn’t stray into adjacent Indian grounds – then negotiating with the Mexican government to allow the trail at all.

After successfully completing that task, George and Mary Sibley returned to the St. Louis area in 1927 – where he helped Mary, a born teacher, start the first school for young women west of the Mississippi, now Lindenwood University. Seeking a newer world indeed.

To put a wrap on this post – less about the river that runs through it than those traveling the river – I want to go back to the roots of that family tree mapped out in the book The Sibley Family in America. That George Sibley, this George Sibley, and the fifty other George Sibleys scattered around the limbs of that one family tree: we were a proper WASP bunch, no doubt. An etymological analysis of the Sibley name is interesting, in a sobering way. The name splits easily into two words with Anglo-Saxon roots still found in the dictionary: sib, related by blood, one’s kin or kindred; and ley/lea, a tract of open land, a meadow.

Lea is the interesting part of the name. Taking the Old English lea back to its roots among the Germanic tribes, who infiltrated England at some point and became the Anglo-Saxons, originally a forest people, the word meant ‘clearing.’ It was also part of a word group associated with the even older Proto-Indo-European root for ‘light, brightness.’

Putting the two words together, then – the Sib-Lea, the people of the clearing. Which is what we were through our undocumented generation in Europe and England, the people of the clearing, the people letting the light into the forest. Which we did until England and Europe were effectively cleared of their forests, precipitating an energy crisis that drove the people to using dirty coal, and also drove them to America, where they began to clear the new continent of trees, of natives, of buried carbon fuels, of topsoil, of whatever a swarming species needed to keep swarming. Dozens, hundred, thousands of bright, honest, dedicated men and women working diligently and efficiently: we are the Sib-Lea, people of the clearing.

***

George, this is wonderful.

Very interesting article. I enjoyed the history lesson and the the tracing of the “famous Sibley” name.

Another interesting report. Ah, Jefferson! Defensible argument can be raised that Jefferson holds title to a dubious honor: the biggest hypocrite in our history who was nonetheless irreplaceable, though how can we ever know? Who else among us could in what must have passed for good conscience, forced “God’s chosen people” to work the land…or whatever? And, though said to be brilliant, to have gone against so much popular sentiment to shell out (though for prime real estate a bargain) big bucks for more land for God’s chosen” to work, reasoning that slaves from the south would move west but not further multiply, thereby—through sheer diminution—end slavery? The Sibley who craved moving, “seeking out new worlds”? Not my George, a man who more than any other loves his little valley. Maybe a once-a-year jaunt, sort of a toe in the water, but to really light out for the territory? Hmm. Well, now that I think about it, yes, back in the day—this current Sibley himself came west, seeking a new world. And by God he proved to be chosen and found it! But how do I know MY George cannot be even distantly related? Trading and selling arms and ammunition to Natives, doing what he could to help take the land away from them, then skipping? Heading back to the city so his wife could work for their living? Nah! That George Sibley must have been adopted.

No one ‘seeking newer worlds’ today, or even ‘lighting out for the territories,’ would look for them on or near the interstate highway system….

And Click is Scotch Irish for… stepping stones.

George,

Great reading.

Paula

A great exercise, George. One that we are invited to participate in. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing your photo gazing out over the river, a great shot–by Maryo, I suppose. “Hi” to both of you.

The ease at which you delve into Americana expansionist philosophy is perfectly complimented by your writing. I always look forward to receiving your posts.

I so enjoyed this piece. I love learning about the roots of words. The story of the Missouri and your “ancestor” are fascinating!!! Thank you very much.

Sandy C.

Another great exposition, George. It identified, to almost the second, how and when the dominant urge of people went whole hog into the heated, population-driven Goodies-O-Sphere (which, of course, is the theme of my book).

Thanks again!

Facinating reading….all connected to the river

As always, George, informative as well as entertaining. Looking forward to the next river tale up here in Oregon, land of uncountable pools, ponds, sloughs, streams, creeks, rivers and the mighty Columbia.

Gracias,

Vince

Fascinating