By 1900, the Americans were ready to take on the Colorado River, economically, politically, psychologically – and perhaps most important, technologically.

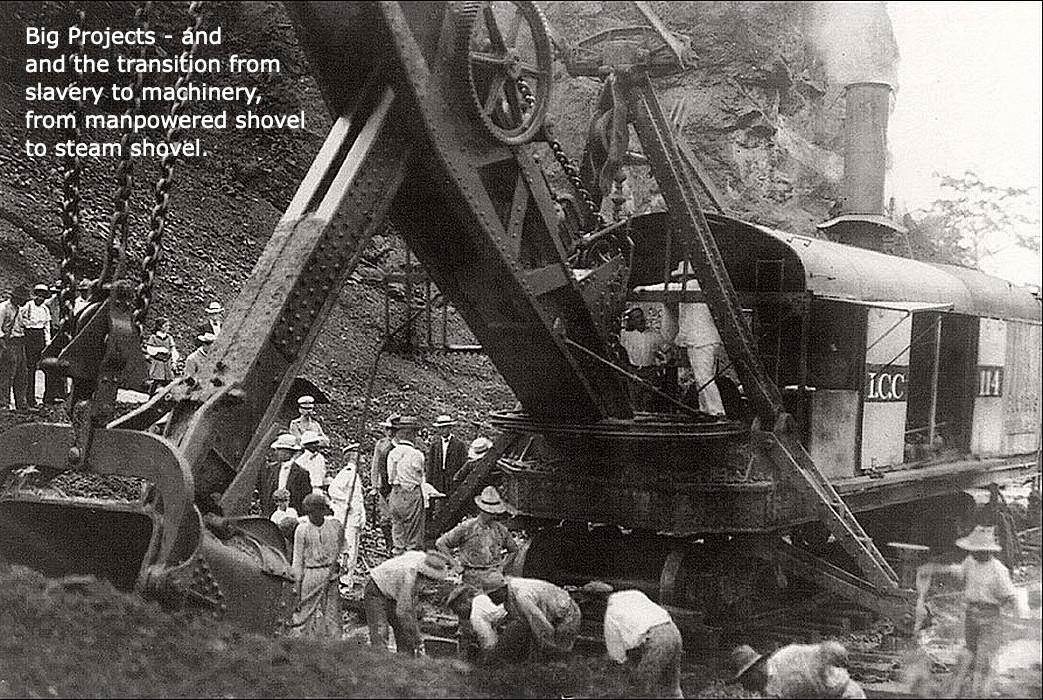

In 1904 the United States went to work down in the tropics, far from home, on the Panama Canal, undertaken to shorten by weeks the boat trip from the Pacific ports to the Atlantic ports. This was a project comparable to the building of the Egyptian pyramids and the European cathedrals, all done with human and horse power. If you don’t have a bulldozer or power shovel and a truck the size of a house to move dirt around, then you give a hundred men shovels and another hundred wheelbarrows.

Where do you get the two hundred men? All previous civilizations depended on slaves acquired from surplus populations or conquered peoples for the heavy lifting. Sometimes it was paternalistic slavery like we practiced in the quasi-agrarian South, where the slaves were ‘owned’ and to one degree or another fed and housed by their owners; sometimes it was wage slavery like we’ve practiced in the industrial North, where the slaves were not owned (no paternalistic obligation for the industrialists), and were free to leave their miserable mechanistic jobs and go starve to death more quickly than they would eventually anyway on their ten-hour shifts for miserable wages.

The Panama Canal project was probably typical of the beginning of the segue from the need for slaves to do the big works and heavy lifting a civilization needs (especially an irrigation civilization), to turning all that manpower and horsepower work over to increasingly sophisticated and powerful machines, powered by the new fossil fuels. By the time it was finished in 1914 the canal project had used – used up – untold thousands of laborers; the official death toll for workers was over 5,000 (of which only 350 were white), most of them killed by yellow fever or malaria, but many historians, assembling bits and pieces of information, think the total project death count may have been over 20,000 (counting those from the French beginning of the project). But the project also had steam shovels, steam tractors and trucks, early bulldozers and other ‘paleoearthmovers;’ It was no longer just men with picks and shovels at the interface between the rough stone of the planet and the drive to ‘fit’ the planet to the visions of a swarming species. The full transition to replacing slave labor with machines driven by fossil energy took the first half of the 20th-century.

It has been said that war time often inspires a lot of creativity; big projects like the Canal also spur creativity in technology. The parallel is apt: as we began to tap the immense potential of petroleum and coal to drive the increasingly powerful engines of the Industrial Revolution, our Western Civilization effectively set out to wage war on the vagaries and difficulties presented by nature – not to destroy nature but to get it in harness, to make if better fit and fill the needs of our ever increasing populations. The Ascent of Humankind – the advent of the Anthropocene.

Meanwhile, back on the Colorado River: In 1902, pushed by the clamor of William Smythe’s Irrigation Congresses, and also still moved by the agrarian vision of a nation of family farmers on their own land, the U.S. Congress created the Reclamation Service in the Interior Department, assigning it to the Geological Survey. Given the ambitious nature of the times as expressed by Smythe and the Irrigation Congresses, to make the whole desert bloom like the biblical rose, the charge to the Reclamation Service was rather modest: they were to help groups of farmers staking claims in the arid lands to develop organized irrigation companies and efficient, effective and affordable irrigation system for their lands. The Service also offered low-interest loans to develop the systems. More engineers were hired, in addition to the corps of surveyor engineers.

Technical assistance and affordable money – a recipe the government would use again in a nation of ‘ruged individualists’ still ambivalent about ‘big government,’ but dreaming dreams beyond the scope and scale of profit-driven private enterprise. Even the progressive president Theodore Roosevelt was still very cautious about ‘intruding’ in economic and social issues considered to be better guided by Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand – don’t get in the way of entrepreneurial individuals seeking a niche to provide something useful for the society, which makes the economic society move right along producing everything that is needed, supposedly.

But remember from a previous post (May 24 2022) the two real problems settlers had with the Colorado River: first, the flood of snowmelt for two months in the spring and early summer that was hard to manage and that filled the ditches with silt – then, second, a flow too low in the late summer when water was needed to finish the crops. Working down on the ground with the would-be farmers, the Reclamation Service was unable to do anything about those problems of water supply – too much or too little. The Service which knew the solution for both problems was storage upstream from the land being irrigated, but this was far beyond the means, even with low interest loans, of the farmers they were helping set up local irrigation systems that would all experience those same basic problems.

This undoubtedly resulted in some tension between the engineers in the Reclamation Service who longed to take on the storage challenge – employing all that incredible emerging technology in building dams – and the science-based Geological Survey with its disciplined approach to looking before leaping, understanding the nature of nature before intruding on nature. The engineers tended to be of the mind that humans had unleashed the power that enabled us to just go ahead and change nature to better meet our needs, and wanted to get after it.

Everything began to change around 1905. That year, a rogue autumn flash flood from the canyon region roared down the Colorado River and blew out an irrigation cut into the old seabed renamed the Imperial Valley; within days the entire river was running off the north side of the dike it had thrown across the Gulf of California, turning the Salton Sink into the Salton Sea and washing out a lot of new agriculture. As an investor in the Imperial Valley, the Southern Pacific Railroad undertook the task of undoing what was essentially an inevitable geological-scale event, given the pulsing silt-laden flows of the ever-changing river. The railroad nearly bankrupted itself, spending two years and millions of dollars ‘correcting’ the situation, finally getting the river to again run off the south side of its dike and not into the Imperial Valley.

That was a big flashy example of the problems faced by hundreds of much smaller irrigators throughout the Colorado River Basin, from my great-grandfather up in the headwaters region to the homesteaders down in the desert being assisted by the Reclamation Service; trying to work with the Colorado River was like trying to drink out of an on-again off-again firehose. The Salton situation was big enough to catch the nation’s attention, and made it evident that only the federal government had the financial resources to really take on controlling the wild Colorado River.

The Reclamation Service was champing at the bit to get into bigger projects, and in 1905 launched into three interesting challenges with established irrigation organizations. One was the largest masonry dam anywhere, to resolve the storage and flood problems: this was the Theodore Roosevelt Dam on the Salt River above in the canyons off the Mogollon Rim to the growing city of Phoenix, irrigating the eastern Sonoran Desert – the site of the old Hohokam civilization, hence the city’s name. Built of big blocks of stone and 280 feet high, this was a classically beautiful dam storing, when full, 1.6 million acre-feet of water (maf) for irrigators and domestic users in the Phoenix area.

Another project in the Service’s first Big Five was in the River’s upper reaches, in the Gunnison River Basin. Within a decade of the eviction of the Uncompahgre Utes and the opening for of rich agricultural land in the Uncompahgre River valley, a swarm of farmers had developed all the water that flowed off the north slopes of the San Juan Mountains. And rather than putting up ‘No Vacancy’ signs, the valley irrigators decided to get more water. The Gunnison River ran just a few miles away, but was trapped by a vagary of nature in a canyon it had cut a couple thousand feet deep. It seemed like a straightforward task to just put a tunnel through the wall of granite separating the river from the valley and bring the Gunnison’s water into the valley.

The several ditch companies of the valley pooled their resources as the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association, and tried to start the tunnel. They were barely beyond the reach of daylight when they ran out of money. They appealed to State of Colorado which had created a fund to develop larger irrigation projects, but a $25,000 grant from the state ran out with only 750 of tunnel.

The dream stagnated until 1904, when the UVWUA appealed to the new Reclamation Service, which took on the project in 1905. Everyone had assumed most of the tunnel would be in the same hard but stable granite visible in the Black Canyon walls – which it was from the Gunnison River end. But tunneling from the Uncompahgre end became a soggy nightmare – ‘2,000 feet of heavy water-bearing clay, gravel and sand; 1,200 feet of hard shale and gravel with much seepage; 10,000 feet of black shale with fossil deposits and combustible gas; 2,000 feet through a badly shattered fault zone which held high temperatures, hot and cold water, coal, marble, hard and soft sandstone, limestone, and concentrations of carbonic gas; and 1,455 feet of metamorphized granite with water-bearing seams,’ according to the Bureau – which had to become more than just technical advisors when no contractors could be found for the work.

It was as dangerous as it was difficult; 26 workers died on the job, and many more were injured; the average duration of employment (at around $2.35 a day) was two weeks. But the tunnel was completed in 1909 at a total cost of $2.5 million, much more than the original estimate. It was the longest irrigation tunnel in the world at that time, and capable of moving half a million acre-feet of water from the Gunnison River to the Uncompahgre Basin – about a fourth of the Gunnison Basin’s total water. The project was dedicated September 23, 1909 by President William Howard Taft himself.

A third big project the Reclamation Service took on in 1905 was the first dam on the Colorado’s mainstem, at the Laguna Project headgate a few miles above Yuma and the delta. This was a rock and concrete weir dam only ten feet high but almost a mile wide bank to bank – looking something like a highway built badly out of level. It stored no water, but was just intended to keep the river level up to the Laguna headgate in the low flow season. The Laguna headgate and weir were basically abandoned only thirty years later, overrun by larger visions – but that is another story we’ll get to.

These were expensive projects, large for their time, for which the beneficiaries are still paying three generations later, but would probably all say has been worth it. And the Reclamation Service’s enthusiasm for these larger engineering projects probably explains an Interior Department reorganization in 1907: the Reclamation Service was removed from the U.S. Geological Survey and made an independent ‘Bureau of Reclamation.’ This was more than just a bureaucratic reorganization; it was to some extent the uncoupling of science and engineering.

The Geological Survey had developed a discipline of science-before-settlement and incremental development through the tenure (1881-1894) of its formative director, the scientist-explorer-politician John Wesley Powell. Engineers, on the other hand, at the turn of the 20th century, were enchanted by the incredible technological capabilities being developed through the application of fossil energy. They had visions of their own, and were impatient with the little local projects under the auspices of the Geological Survey. They might not have said it aloud, but their larger 1905-1910 projects seemed to demonstrate that human dreams no longer needed to be ‘fitted’ to the natural conditions in which humans found themselves; instead, the natural conditions of the planet could be culturally altered to fit any human visions. This they drank from the romantic waters of the Hassayampa, this was the Romance of Engineering – and the full onset of the Anthropocene.

Before they could really go to work, however, there were problems to be worked out beyond the scope of either engineering or science…. Stay tuned.

Great history George. Thanks.

We (the nation) are wonderful in our ambitions . unfortunately the laws of unanticipated consequences always seem to be in play. I love your essays, George- THANKS