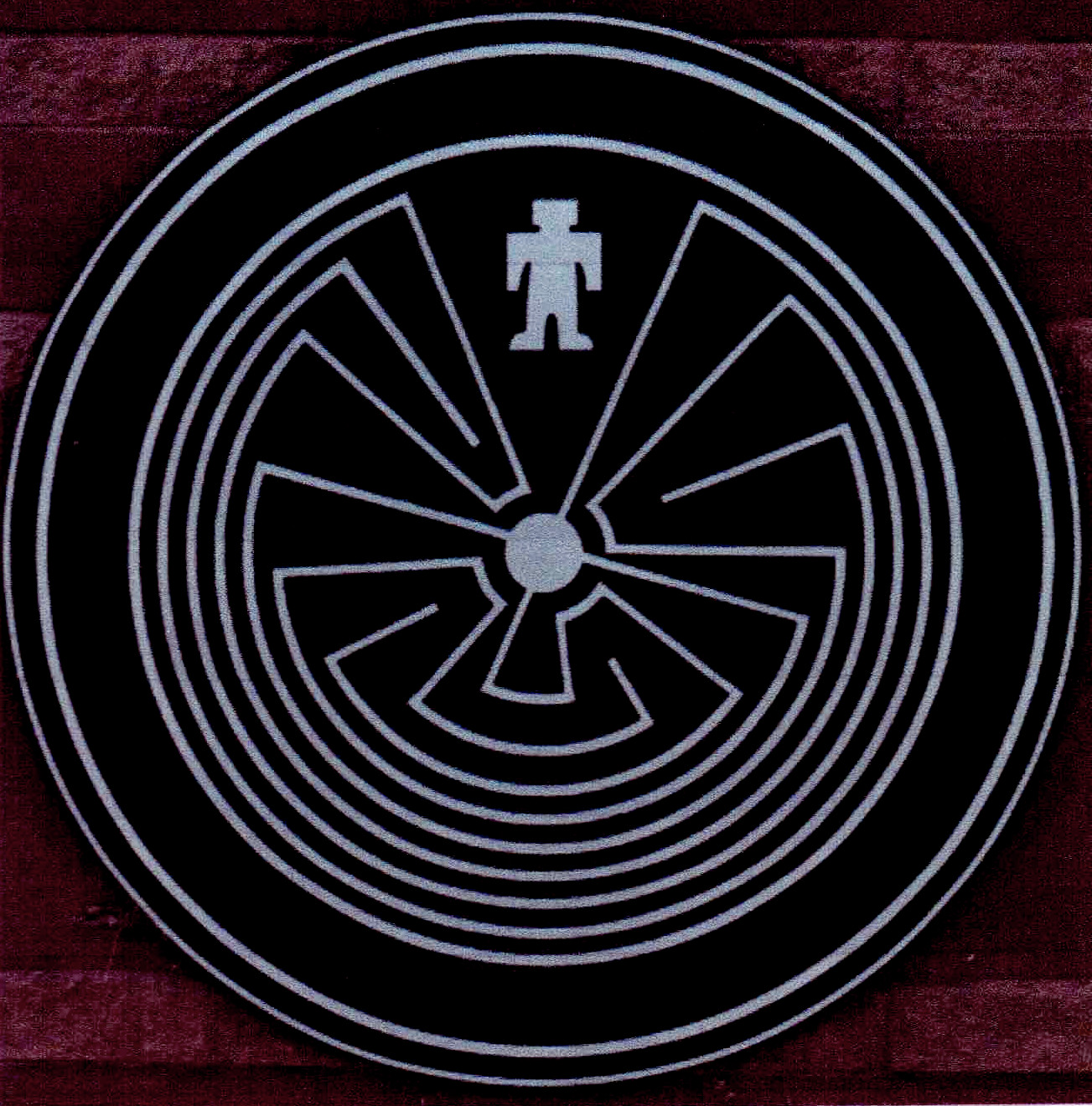

The maze design above is the Great Seal of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, inhabiting a relatively small First People Reservation (53,600 acres) in Arizona at the confluence of the Salt and Gila Rivers. The Gila River system drains most of the state of Arizona – what there is to drain in the subtropical Sonora Desert. The Gila joins the Colorado River at Yuma, near the Mexican border. The reservation was created in 1879 to get the First People out of the way of the Euro-American tsunami coalescing along the Gila as the city of Phoenix – which has since grown to surround the reservation with suburbs.

Given the kind of heraldic symbolockry that makes up most Great Seals, signifying power and glory – I think that to put a maze on your Great Seal takes a certain admirable chutzpah, the higher humor of those who laugh with their gods rather than just being laughed at by them. But when it comes to water and the Colorado River in general, the maze might be an accurate enough symbol for where we all are today: at the ragged end of a century of building a magnificent hydraulic society that has devolved to a near-collapse at the systemic level. Having cobbled together a strategy for nursing the system under a much-amended set of ‘Interim Guidelines’ through to the end of the interim in 2026, the water mavens of the Colorado River Region are now working, not exactly together, on a plan for operating the river post-2026 for at least a couple decades further into the 21st century. At this point, the Bureau of Reclamation has received at least four alternative post-2026 management plans at this point: one from the four states above the river’s canyon region, one from the three states below the canyons, one (at least) from a group of environmentalists, and one we might call the ‘elders’ plan’ submitted by Eric Kuhn, Jack Schmidt and their scribe John Fleck. Welcome to the maze: these alternatives will all be analyzed through an Environmental Impact Study over the next year or two or five, and e pluribus unum, a management plan will emerge like the sun at the center of what ought to be the Great Seal of the entire Colorado River.

There is, however, probably no set of river users more experienced at wandering in the maze than the 30 tribes of First People on reservations in the Colorado River Basin. They have been finding their way for a century and a half in a maze whose dead ends for them were to be the end of their cultural lives, if they didn’t backtrack and try another way. But they have now, at this point, come through most of those trials and achieved a growing acceptance of the cultural diversity they bring to American society; the government is no longer practicing an active policy of forced assimilation; and there is a growing interest in their cultural and spiritual ways.

But they seem to still have trouble being taken seriously in the Colorado River Basin as potentially part of the solution of the water challenges rather than just objectified as part of the problem. They have not submitted a post-2026 management plan per se; they have instead submitted a three-page letter that is something between a request and a demand: first, that the federal government meet its trust responsibility to Basin Tribes by actively protecting their Tribal water rights from being first-to-be-cut (irrespective of whether they have already been finally quantified); second, that the government eliminate systemic obstacles to their full development of their water rights; and third, that the government provide a permanent, formalized structure for Tribal participation in implementing the Post-2026 Guidelines, and in any future Colorado River policy and governance. (Click here for their letter.)

As usual, this wants a little historical context. Any discussion of ‘Tribal Water Rights’ requires, for example, a clear understanding of the distinction between ‘paper water’ and ‘wet water’: ‘paper water’ is water which one has a legal right to use; ‘wet water’ is the amount of paper water one can actually afford to put to use with money, time and will.

In 1908 the U. S. Supreme Court gave – or appeared to give – the First People tribes a lot of paper water with a very senior right: in a Montana case involving settlers in the Milk River valley and the Ft. Belknap Crow Reservation, Winters v. The United States, the Court said that whenever the federal government reserved public lands for any purpose, it also implicitly reserved the water necessary to carry out that purpose – and the priority date for that reservation of water would be the date the reservation was created. Also, the standard ‘use it or lose it’ mandate of the appropriation doctrine would not apply; the water right would be there whenever the reservation was finally able to develop its paper water.

This ‘Winters doctrine’ was a real wild card dropped into the federal government’s relationship with the First People at the time. Government policy toward the ‘Indian problem’ by the turn of the century had advanced beyond ‘the only good Indian is a dead Indian,’ to a policy of forced assimilation – ‘Kill the Indian to save the person.’ It was a policy change from an Indian War waged by the cavalrymen, to cowboy work for the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA): round’em up, corral’em, feed’em – but don’t let’em get too comfortable because we want to move’em on into good jobs and a better life as ‘real Americans.’

And the OIA cowboys rode for the USA brand, not the Indians. Theirs was the job of carrying out the 1887 Dawes Act, whereby reservations for people who had only known the land and water as commons for everyone (in their band) to use, saw the land divided into private farm plots which they would own individually and be individually responsible for (whatever that meant). Their children were torn from family and clan and hustled off to distant Indian schools were they were taught industrial skills and the advantages of no longer being an Indian. The goal was to facilitate the disappearance of the ‘Indian problem’, into the farm towns and industrial cities surrounding the reservations, with a liquor store just down the road at every exit.

The Winters doctrine was also an unexpected and unappreciated wild card played in the federal-state relationship. Until that assertion by the nation’s highest court, water matters had been left to the states since there was no one-size-fits-all for the variability in climate, state by state. But the creation of federal reserved rights for water in the arid states was capable of blowing large holes in the state-level prior appropriation doctrine the arid and semi-arid states had all adopted as grassroots common law. Dating the reserved water rights to the creation dates of the reservations made the First People (not unjustly) senior to practically every other user – and then allowing the reservers to hold the water right indefinitely without putting the water immediately to beneficial use – it was easy to see the federal reserved right as a deadly attack on the appropriation law.

The states eventually struck back at the concept of the federal reserved right. The U.S. Congress tamed the federal reserved right somewhat in 1952 with the McCarran Amendment by Nevada Senator Pat McCarran; this mandated that any federal reserved right would have to go through the standard water right adjudication procedures of the state(s) involved. Further court decisions said that quantification of the reserved water right was limited to the primary purpose of the reservation, and the decree could only be for the minimum amount of water necessary to fulfill that purpose.

On the positive side for the First People, American public opinion about them was mellowing through the first third of the 20th century, as reflected in the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. This mostly reversed (for at least a couple decades) the more brutal aspects of the assimilation policies, and restored some local control over First People land and resources; the People were encouraged to create their own tribal governance. The often heavy-handed trustee relationship with the OIA cowboys continued to be a very mixed blessing (especially where water was concerned), but at least self-governance gave them the opportunity to raise a unified voice.

Water continued to be problematic, however. In considering the importance of the federal reserved right in the Colorado River Basin, it is important to note that less than half of the First People tribes were being rounded up and herded in from hunter-forager lives – or as that life had evolved due to the presence of Spanish horses and the crowding due to population growth and white pressure, the hunter-gatherer-herder-warrior-raider life. These were tribes like the Utes, Navajos, Apaches and Comanches who had decided that, rather switching to agriculture, they would rather fight each other and the Euro-Americans over territory, horses, slaves, and plain love of the skirmish, while raiding more settled People for their subsistence.

Meanwhile, many other First People were well into the transition from hunting and foraging to farming. As the gold and silver rushes brought on the white tsunami in the 1850s and 60s, two First People tribes farming on the Colorado River floodplains and hunting in the adjacent uplands – the Mojave and Chemehuevi – actually requested that the Office of Indian Affairs create a reservation for them on the river floodplain, yielding their upland hunting grounds for a place the white settlers could not invade.Reservations for the Mojave, Chemehuevi and ‘Colorado River Indian Tribes’ (both tribes) were duly created near where California, Nevada and Arizona intersect. Small tribes farming farther down the river also received small reservations, some for groups of only a few hundred people.

Then there were the First People who had been irrigating farmland from time immemorable in the Gila River Basin, mostly branches of the Tohono O’odam People like the Pima and Maricopa, who traced their heritage and culture back to the Huhugam (Hohokam) hegemon that had prevailed in the Gila Basin several hundred years before the Spanish Entrada in the Southwest, and (like all advanced ‘civilizations’) collapsed mysteriously, probably from some combination of over-population and unsustainable economic and cultural complexity.

Many of the First People in the Southwest did not, in other words, even need the supposed advantage of a federal reserved right; they could have filed directly into the state adjudication system for the right to water they had been using beneficially since well before the Euro-American invasion – if their supposed trustee, the OIA cowboys, had explained the new laws to them and shepherded them into and through the adjudication process, standing up for them as Congress had supposedly charged them to do.

Instead, the First People found their water disappearing as the land filled in around them, upstream and down, and their physical and cultural lives deteriorated accordingly, as well as their sustainable economics. The white settlers irrigating their own lands were not consciously stealing Indian water; they were just participating in the first-come first-served race for resources that the prior appropriation doctrine sets up, and the First People were not privy to the procedures for getting into that race.

The cultural undermining of the Gila River Basin First People in the late 19th century falls entirely on the failure of their government trustees to help them negotiate the bewildering new appropriation systems. But that is a historical judgment that has to balanced with a little empathy for the OIA cowboys themselves, trapped in the history of America’s cowboy epoch. They undoubtedly believed they were just carrying out federal policy, which was assimilation of the First People – forced when necessary. The ‘pot’ looking today at that ‘black kettle’ has to be aware of the fact that our government still seems to be dominated by representatives who believe – perhaps not consciously – that keeping conditions on the reservations generally miserable and hopeless helps bring the First People along to leaving the reservation and becoming real Americans. Otherwise, why would we allow conditions to remain so bad on so many reservations?

But this not a story with the usual unhappy ending. The fact is, some of these First People reservations are bootstrapping themselves back into a state of reasonably well-watered economic and cultural vitality, and are doing a lot of it on their own impetus, with their cowboy trustees riding shotgun to help as necessary with authority and funding. They have actually acquired quite a lot of decreed paper water – a full third of the total current flow of the river – but they have only been able to put maybe a fourth of that to work as real water. They will tell you that they are not done – as their letter to the Bureau indicates – but will also say they want to work out the use of their water so consumptive use does not increase significantly.

We will look more closely at that apparent contradiction, and how it is unfolding, in the next post.

Meanwhile – welcome to the maze. Where it might make sense to stop, look and listen to those who have been here longest.

George,

If others could write about our water story with your insight, clarity, and sense of humor, we might, just maybe, get more folks to read and educate themselves about our water dilemma. Thanks for continuing to make your excellent contributions.

Ranger Curt

Indeed, paying attention to one’s elders (historical, cultural, ecological) makes a good deal of sense. It’s also an appropriate time to refer back to a line I learned years ago, but that seems applicable to this situation: “To the privileged, equality feels like oppression.” This might be a good time NOT to be a rancher.

Fascinating, George. You know how to tell a compelling story. Fondly, g

Super! again. It barrels into the penultamit problem: i.e. the human horde who headlonged himself into every square meter (that he likes, anyway) and then mindlessly keeps trampling up the limited land, water and ecosystems on earth. “First People’ , I hope will have input into the world of the 22nd century, where (mindfully) homo has reorganized himself to have a sane, less wack a do cowboy society and planet. I have added a litttle section in my book on this aspect.