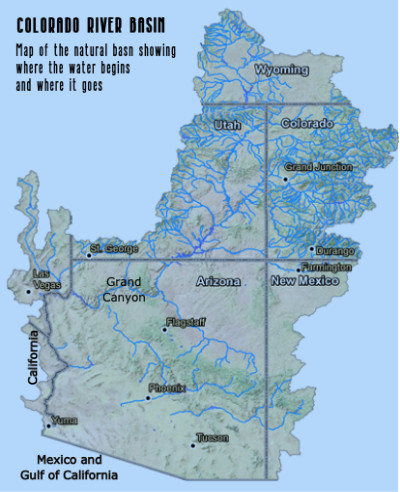

Unless you’ve been living in a media-free cave somewhere, you are probably aware that the Colorado River is again prominent in the news. What’s not really noticed, but ought to be, is the extent to which we find ourselves today almost exactly where we were 101 years ago this winter, with six of the Colorado River states in tension with the seventh state over basically the same topic: the appropriateness of appropriation law as the only legal means for allotting use of the river’s water.

The line of conflict today is being drawn over the increasingly depleted state of the two big storage reservoirs on the Colorado River’s mainstream, Mead and Powell Reservoirs. The Bureau of Reclamation, the ever-optimistic manager of the river’s storage and distribution system, has finally acknowledged that its reservoirs are getting uncomfortably close to a ‘dead pool’ situation whereby it would not only be unable to generate electric power, but would even be unable to get any water at all downstream from the big dams for much of the year. So they have issued two moderately panicky mandates that the states have to cut their uses dramatically in order to save the system: two to four million acre-feet (maf) of cuts from a river currently running only around 12 maf a year on average under nature’s imposed burdens of aridification – cutting between a sixth and a third of current use.

Part of the problem is probably a longer-than-usual dry spell in the natural order of fat and lean years. Another more permanent part of the problem is a warming climate that is depleting arid-land water supplies at a rate of around six percent for each additional degree Fahrenheit in average temperature. But a larger part of today’s problem is a century of increasingly bad management of the reservoirs, on the shaky infrastructure of a body of legislative acts, court decisions, environmental laws, and other interstate and intrastate agreements and contracts known as the Law of the River.

The Bureau has twice issued its mandate, first back in the summer of 2022 and again in December, saying that if the seven states cannot come up with a plan for such cuts, the Interior Department would do it for them. The states called its bluff the first time, but this second time – acknowledging the growing severity of the situation – six of the states came up with a plan for cutting usage by almost two million acre-feet. But a seventh state refused to sign on, and came up with its own plan. And it’s deja vu all over again.

Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming submitted the six-state plan, proposing just under two million acre-feet in cuts, mostly through finally reducing usage by Lower Basin states to account for evaporation and other system losses from Lower Basin reservoirs and delivery canals and the Lower Basin’s share of the Mexico allotment. The Upper Basin would suffer no further cuts initially in the two million acre-foot reduction.

California refused to participate in that plan, instead offering a nine percent reduction in use but wanting its massive senior water rights given priority, with Arizona accepting the junior status for all Central Arizona Project (CAP) water, agreed to the 1968 enabling legislation in exchange for California’s support for the CAP.

In 1922, remember, those seven states had gathered to try to work out a perceived problem, the same six against California. All seven states allocated use of the waters of the river through the appropriation doctrine, which had evolved on local watersheds everywhere in the arid and semiarid lands of the West – the down-on-the-ground rules that enabled individuals to appropriate from the public commons both the land and essential irrigation water they needed in order to make a life and a living, with rights to use the water determined by priority of use: first come, first served – determinations often worked out vigorously in the early days at headgates, sometimes with deployment of shovels or shotguns.

This common law was evolved enough when territories became states, to enshrine it in state constitutions. But the ordering of prior appropriations became complicated as local watersheds had to fit their adjudications for priority of use with those of larger downstream confluences, with whole river basins eventually sorting out priorities that might result in senior users a hundred miles downstream placing calls on headwaters users who were seniors on their local stream but juniors on the larger river.

That situation was supercharged as free water and free land became a powerful engine for growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. All seven of the Colorado River states at least doubled their population in the first two decades of the 20th century – but California’s population quintupled in that same period. And all seven states also realized that the logic of the appropriations law meant that states sharing a river would have to acknowledge priority in each other’s appropriations – and one California development company, clear down by the delta, already had a 1901 decree for more than two million acre-feet of the river’s water for converting the barren Salton Sink into the Imperial Valley….

The other six states feared that, with no law governing the distribution of water use other than the appropriation law, California’s uncontrolled growth might tie up most of the use of the river while they were still just getting started on their own uncontrolled growth. At best, it would be a seven-state horse race to appropriate as much water as possible as quickly as possible, in a competition that would hardly assure orderly and truly beneficial use. At worst, the slower states would simply be cut out of any significant water for development.

I think of it as ‘Caliphobia’: fear and loathing (and maybe a little envy) of California, the state that always seems to be ahead of everyone else in everything. Caliphobia occasionally still re-emerges today, and not just among western states. What the six states wanted was some kind of a mutual but enforceable agreement that would divide the use of the river’s water equitably among the seven states, independently of the appropriation laws; they seemed to wanted appropriation law to apply at the state level, but maybe not always at the interstate level.

California had no fear of the other states, but they had a need of their own that prompted them to sit down with the other states to work out their problem. California needed the interstate river to be controlled by at least one large structure, capable of capturing and storing the river’s annual snowmelt flood and distributing the water more evenly through the rest of the year. The company developing the Salton Sink/Imperial Valley had been bankrupted by a rogue 1905 autumn flood that had managed to divert the entire river from the delta down into the Sink, turning part of it into the Salton Sea – the whole area was actually a segment of the Gulf of California that had been diked off by the debris moved by the river in grinding out the Grand Canyon; it had dried up leaving the Imperial Valley as much as 300 feet below sea (and river) level. An interesting irrigation challenge.

So California wanted a big dam that only the federal government had the resources and interstate authority to build – and the Interior Department and Bureau of Reclamation were chomping at the bit to take on that challenge. But westerners in Congress made it clear that there would be no funding for such a project until the other basin states were assured that they would each have an equitable share of the controlled river’s water to develop. The states themselves wanted to maintain as much control over the water as possible, so they sought permission under the U.S. Constitution’s compact clause to form a compact to divide the use of the river among themselves. Congress gave them a year to do that, and they assembled in Washington in January 1922, seven commissioners with Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover as chair, to create a Colorado River Compact.

Their goal going into the compact meetings was to come up with a seven-way division of the consumptive use of the river’s water that would enable each state to grow to its full potential in its own good time. But that goal itself was basically impossible at that time. In the first place, they did not really know how much water the river had to divide; the guesstimates they had to work with varied between 13 and 17 million acre-feet per year.

And in the second place, and even worse: the only information about their own future needs they could bring to the table was their wild ambitious dreams; the sum of their estimates of each state’s irrigable land and the water needed to irrigate it added up to more than half again the Bureau of Reclamation’s always optimistic estimates of the river’s flow. They had nothing but vague rosy ideas of their potential industrial growth.

The Bureau had its own more objective estimates of how much water each state could probably use, fitted to its own optimistic estimates of the river’s volume, but the states were not interested in those numbers; they would only accept their own estimates of their own glorious futures (while criticizing everyone else’s).

Such a seven-way split could only have been done in a context of setting limits anyway, and that was against the spirit of the times. This was the Early Anthropocene: having discovered the apparently unlimited power of mineable carbon, and designing formerly unimaginable machines and systems fueled by those carbon fuels, the state engineers and the engineers in organizations like Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation were ready to go nose-to-nose with nature, impatient to teach natural forces like the rampaging Colorado River to stand in and push rather than cut and run. Welcome to the Early Anthropocene, when the sky was the limit only because no one was yet thinking about outer space. While six of the basin states feared California’s fast start and uncontrolled growth in developing the river’s water, what they basically all wanted was to be California in their own good time, experiencing uncontrolled growth and the resulting uncontained wealth.

After a frustrating week of working on that seven-way split, they were on the verge of abandoning the whole effort; but they all did want to get the federal government involved in developing the river (on their terms, of course), so they had to come up with something that would satisfy Congress that Caliphobia had been addressed. After a spring and summer of letter-writing and phone calls, they reconvened in Santa Fe in November, a month and a half from their deadline, in a do-or-die push to come up with a feasible compact.

We’ve looked in previous posts here at difficulties the Compact commission tried to address in that final eleven-day effort, and also at the difficulties their ‘alternate solution’ imposed on the river and its users for the century following: the division of a desert river into two basins, separating the source of water from the main flow of the water; the bad guess on the volume of flow, resulting in an unequal division; and perhaps worst of all, making the Upper Basin responsible for delivering a relatively even and constant flow to the Lower Basin regardless of what desert-river vagaries the upper states were experiencing. Most of that could have been avoided if they had been able psychologically to submit to the limiting aspect of the seven-way split of the river’s use they thought they wanted, measured and administered by a balanced river commission of their own making. They were just not up to that; it was too early in the Anthropocene. Without going into specifics, it is hard to find anything in the subsequent agglomeration of legislative acts, court decisions, interstate and intrastate agreements, and other things bundled with the Compact as ‘The Law of the River’ that did much to relieve those difficulties, until the environmental laws of the 1970s began to corral some of the random growth driven by appropriation law.

All of which may have something to with why, today, 101 years later, we find ourselves in roughly the same situation: the six states in a stalemate with California over alternatives to straight appropriation from the commons. But at this point – couldn’t we start by finally doing the division of the river among the states (and Mexico) that couldn’t be done in 1922? Aren’t we what Hoover, in the 21st Santa Fe meeting, called ‘those men (and women now) who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information’ and capable of making ‘a further division of the river’?

More specifically – after a century of developing the river for use, with the river’s use almost certainly over-appropriated – can’t we acknowledge that the seven-way division has actually been accomplished? The seven states all have what they have and there isn’t any more to appropriate. All we need do at this point is to acknowledge that fact and put numbers on it – the actual numbers of what the states are all using and reusing today, no Compact fictions. There are those in each state who will say, but, but, but what about…. But – really.

I will not pretend that this would be a simple matter, and it would require a largeness of spirit we may still not be capable of bringing to it. Without even looking at any numbers, we can state with certainty that the four states (including Mexico) below the canyons are getting the use of approximately twice what the four states above the canyons get. This is not equal, but might it be equitable? The lower river agriculture is considerably more productive than upper river agriculture, and the lower river and out-of-basin diversions have the vast majority of the 40 million people needing some of the river’s water. And speaking only for myself, that’s fine with me; I’d rather see the water going to where the people are than see the people coming to where the water is.

What is not equitable, and would need to be changed (with a largeness of spirit), is a firm delivery for some users, with other equally worthy users bearing the brunt of both natural and cultural variability in flows. Once the numbers dividing our paltry 12 million acre-feet eight ways (including Mexico) are determined, they will need to be converted to percentages – the way the four upper states did in 1948, given their uncertainty about the available future flow. As the river loses water to rising temperature, the percentages could stay the same but the volume of water per state would drop accordingly.

All eight user-states would also have to take a share of the two million acre-feet of annual system losses, prorated by some no doubt complicated formula. And there would have to be a large-spirited agreement to leave some of the water from the occasional fat water years in the reservoirs, to build reserves for the probably abundant lean years as we move into our self-made future.

The alternative to that kind of process at this point is probably a decade in the courts with those who want to stick with the appropriation laws as is, as the foundation Law of the River, versus those who realize it is time to move on to more equitable ways of allocating a scarce resource to millions who have no opportunity to appropriate the water they need. Heaven knows what might happen with the river in that decade. It is instead time to do some version of what the Colorado River Compact commissioners knew needed to be done, but could not bring themselves to do, so caught up were they in the romance of the Early Anthropocene. We are now, as the song goes, sadder but wiser. Or so we should hope.

Expect some playing around with ideas for this in future posts. And I’d love to hear your thoughts on it: how should the river in the desert be distributed, respecting but beyond first come, first served?

***

Excellent update on the Colorado River Compact mess we’re in. The only thing noticeably missing from the call for the seven states & the Fed to come to some equitable agreement on allocation of the river water would seem to be the absence of recognition that our Indigenous nations and Mexico need a seat at this table, if table there will be. One hopes that here in the rapidly deteriorating climate of the Anthropocene we won’t end up in Originalist courts, giving each state sanction to ignore any federal, Indigenous or Mexican joint common good.

You’re right, Art. I’ve included Mexico as an ‘eighth state’ in my analysis, but the 30 tribes with their federal reserved rights represent a system-breaking challenge: if the federal government is going to take itself and its responsibility to the tribes seriously, then it is basically time to forget the Compacts and the basket of odds and ends called the Law of the River, and start over with a new allotment process….

After years, 50 or so, thinking California was a leader in most things water, the last decade has proven the opposite. Because of abundance the state has been careless and wasteful. Even during most of the plus 20 year drought conservation has been termed “rationing” and what little groundwater management put into place was so far into the future that the large farms have already sucked the aquifers dry. As always, money wins the battle, especially in California. i am not optimistic. There are no towering water leaders. I am no longer sure there ever were.

Our water mavens continue to try to pump up the 1922 Compact Commissioners as ‘towering figures,’ but it is hard to read the Compact transcripts without thinking they were basically engineers and water lawyers in over their heads, grasping for straws like ‘divide and conquer, it worked for Caesar sort of’…. We’ve been a lot better at big physical superstructures than we’ve been at legal infrastructures.

It occurred to me the other day that Powell Reservoir is basically storage for the Lower Basin, but the Upper Basin pays the evaporation charge for the it. Coring out the diversion tunnels and ‘filling Mead first’ would make somewhere between 3 and 5 hundred thousand acre-feet available for the Upper Basin….

Thanks George. It seems to me that getting the eight stakeholders to agree to the principle of allocation by percentages rather than fixed amounts is the first step, and of course that’s a challenge in and of itself. Then the negotiations (read fights) become what the percentages should be and what baseline is used. You suggest that since current distribution is a fait accompli, let’s agree to use it. Why not? What better? Admittingly, I haven’t read other suggestions, but yours seem reasonable to me. I’m looking forward to future reflections.

Thanks, Hap. It seems incredible to realize that people in our own state who should know better are still trying to slip a little more water through their tunnels to the Front Range. They have promised to only take their new water in ‘above average’ water years – but that is water the whole basin really needs to recharge the reservoirs. If we were to go to percentages of the water that appears to be somewhat dependably available, then Colorado is already using a little more than its 51.75% of the Upper Basin water, as agreed in the Upper Colorado River Compact….

I like your thoughts of equitable distribution, but suspect there will be a whole bunch of fighting over giving the productive states more of the share. And I’m not thinking largeness of spirit is something we’re seeing a lot of here these days. The older I get, the more I see, the less I have optimism.

Thanks, Sandy – Truly a lot of matters to work out that can’t be resolved from an ‘I’ve got mine’ perspective.

Wonderful article, learned a lot and well written. “Largeness of spirit” indeed – I suspect we will find this in short supply in the upcoming negotiations…

I share your skepticism about ‘largeness of spirit,’ but I’m holding out hope for Nevada’s Entsminger and Arizona’s Buschatzke….

It’s always a happy moment when I find another installment in my inbox.

George, once again a thought-provoking post. I concur with your sentiment that you would rather see us find a way to send water to California than to have California come to the headwaters of the rivers. One of my daughters lives in San Marcos, California where they seem to have an abundance of desalinated water for their use, and that seems to me to have more potential for the “land of nuts and fruits” than parcing out a scarce resource upstream.

Desalination will almost certainly be part of the water supply solution, at least for the coastal cities. It is expensive and requires a concentrated and reasonably affluent user base; it would quickly become unaffordable if a lengthy delivery system had to be added to the cost of the water…. We could imagine, however, an inland desert city like Las Vegas investing $$ in a coastal plant, in exchange to access for some amount of river water the coastal city might then give up. Creative collaboration may be more the shape of the future than most state are ready to acknowledge.

War may be the only way, though it should not have to be the only answer–the only OLD answer we STILL follow: MAN rules nature, (shall I say) “By God! And so it was written.”

Your idea, based on your years of hands-on experience and study, seems an obvious “possible” solution, and at this point in Nature’s response to MAN’s hubris we may wind up piddling around so long we won’t even have to worry about it. By that time, let the Uppers just take what we need and, like Dylan, leave the rest. “Sue us!” We’ve all been asking for it.

I read in vain for any tiny cause for optimism. Appointment of Sibley as Emperor of the River probably is not politically feasible. Alas.

I haven’t applied for the job….