Voz del pasado

The tragedy of all this is that George McGovern,

for all his mistakes and all his imprecise talk

about ‘new politics’ and ‘honesty in government,’

is one of the few men who’ve run for

President of the United States in this century

who really understands what a fantastic monument

to all the best instincts of the human race this country

might have been, if we could have kept it out

of the hands of greedy little hustlers….– from Fear and Loathing on the

Campaign Trail, Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter Thompson put the term ‘fear and loathing’ into our cultural dialogue in the early 1970s: first in 1971 with ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,’ then with ‘Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail’ in 1973, a long rambling essay into America’s political character based on his coverage for Rolling Stone of the 1972 election of Richard Nixon over George McGovern.

‘Fear and loathing’ is a pretty accurate description of the campaign that Donald Trump ran: fear of a tidal wave of immigrants, mostly criminals; fear of a tidal wave of crime; fear of Promethian women unbound; fear of – well, fear of the future in general, along with a massive denial of things that most Americans apparently don’t want to think about, as discussed in my last post. That those tidal waves of fear were devoid of any factual reality, and the denials chin-deep in ignored factual realities – all that was immaterial; fear and anger work their dark magic best in darkness.

As for ‘loathing’: he and his minions worked hard, with considerable success, to make the gullible loath liberals, progressives, enviros, believers in the rule of law, people wanting to make their own decisions about their own bodies, anyone who still harbors the vision that we can save the planet from ourselves and that life can be made decent for everyone. He and his minions have said, will continue saying, things about people like me that are vicious fictions – I am the evil spawn of the devil just because I’d like to see more equity in our society, and have a commitment to the now-receding hope that we can pass a still-livable planet on to the next generations?

And he won with that campaign. The vote by a majority of my fellow Americans indicate that the Untied States (sic) is no longer going to even be trying to be Thompson’s ‘monument to all the best instincts of the human race this country might have been.’ Not now, anyways. Might we hope that we will recover our more positive vision after four more years with Trump and his dark xenophobic vision? There’s really nothing but hope, but like the guy in the lifeboat said, ‘Pull for the horizon, boys. It’s better than nothing.’

So – back to the river: ‘Let us gather by the river, the beautiful, the beautiful river….’

What were we doing when so rudely interrupted by the election? We were taking advantage of these ‘interim months’ in the Colorado River Basin to engage in a little thinking ‘outside the box’ about the Colorado River, while the seven basin states remain stalemated in the ‘Colorado River Compact Box.’ The Compact’s division into Upper and Lower Basins has devolved at this point to a situation that can legitimately be compared to the 1860 division of states into North and South with a downward spiral toward conflict and chaos. Only in the rich imagination of Paolo Bacigalupi does it descend to open uncivil warfare physically in the Colorado River region (read his worst-case book, The Water Knife, if you haven’t already). But the biggest action step recently in the stalemate was when Arizona’s state director of Water Resources, Tom Buschatzke, asked his governor and legislature to ‘set aside’ a million dollars in the event that going to court becomes unavoidable.

So in our ongoing ‘romance’ with the river, we could either hover and dither over that stalemate, like the rest of the media, trapped in the ‘Compact Box’ – or just take advantage of the ominous quiet to heist ourselves up on the edge of the box, to look over and out at possible alternative futures.

We’ve been exploring the anomaly of a river in a desert – a river created through natural atmospheric processes in a mountainous region of sufficient elevation to force precipitation onto land steep enough so that a large portion of the water created runs off its slopes rather than sinking in – a water-producing region. Whose produced water then runs off into desert lands, where the water produced in the highlands is gradually consumed by the same natural processes – evaporation, transpiration from riparian vegetation, and replenishment of low groundwater tables, and also by human cultures that learn how to use the river to grow things – mainly food crops and cities. The river is not significantly replenished for those losses by precipitation in the arid deserts, so it gradually diminishes, disappears on its way to sea level. The sun giveth the river, and the sun taketh the river away. The vaporized river water rides the wind, usually eastward in search of another condensing factor in the environment, to again become liquid precipitating on the increasingly thirsty earth as we relentlessly drive the planet’s temperature upward.

For cultures trying to live in desert lands with a heavy dependence on a river in the desert, there are two kind of obvious fundamental principles for using the river’s water: 1) first, collaborate on an equitable and efficient division of the use of the river’s water among all its desert consumers, and make that use contingent on the application of best practices in avoiding waste. And 2) take care of the water-producing region in order to maintain or achieve its optimal flows into the deserts. I’ll say that again: it is the responsibility of all the desert water users to take care of the water-producing region for their water, as well as being careful with the water that reaches their desert. Another principle the Colorado River Compact not only ignored, but made worse with the assumption that management of the Headwaters for the river would be up to high-desert users in the Upper Basin, and none of the Lower Basin’s business.

Despite the current disputatious stalemate between the seven states trying to share the river and their division into two camps of north states and south states (with the state boundaries themselves making no geographic or hydrological sense) – there are actually things going on internally within the states, mostly led by the huge metropolitan ‘city states,’ that work toward that first principle of collaboration on the best use of the river and its water. There are water-sharing agreements between desert cities and desert farmers; there are expensive efforts by the cities to maximize efficiency in the use of their current shares of the river, as well as the usual striving for larger shares. Considering that the division of the use of the waters is still bound by the foundational ‘first come first served’ appropriation doctrine, it is all the more remarkable that cooperation and efforts toward maximal and equitable efficiency are beginning to break out here and there, transcending strict appropriation law enforcement.

There is not, however, much conscious and coordinated attention among river users in the desert region for the water-producing region of the river in the desert – the 15 percent of the Basin lands (largely uninhabited) that produces 90 percent of their water. That’s what we’ve been trying to explore in some recent posts – beginning with the river’s ‘mystery’: the fact that of the estimated 170 million acre-feet (maf) of precipitation that falls over the Basin, roughly half of it in the water-producing region, only around 10 percent of that actually shows up in the river.

In a previous post we looked at some of the reasons why so much of the river’s water disappears from the river’s water-producing region – all attributable to sun and wind: sublimation (direct conversion of water from solid to vapor) diminishing the snowpack throughout the whole winter; evaporation as the snowpack melts and forms streams exposed to the desert sun; and transpiration through trees and other vegetation of groundwater that sinks into their root zone. Together these processes consume around three-fourths, at least two-thirds, of the water that falls on the Headwaters.

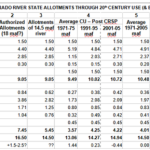

That is a Sibley guesstimate, by the way. We haven’t devised really accurate measures for any of these naatural processes (although there is currently serious scientific work toward better measures). The Western Water Assessment study I’ve been citing is somewhat stuck in the Compact Box, breaking most of its analysis down into Upper and Lower Basin data, which does not work for the ‘water-producing and water-consuming’ model, since most of the Upper Basin is part of the water-consuming desert region (ten inches or less annual precipitation). The WWA estimates the ‘runoff efficiency’ for the whole Upper Basin at 16 percent – an estimated 14.8 maf at the Lee Ferry version of the Mason-Dixon Line from an estimated 92 maf of precipitation – meaning that for every 6 acre-feet of precipitation, only one acre-foot makes it into the river for surface water users. (The WWA estimates Lower Basin runoff efficiency at three percent – one acre-foot dribbling into the river for every 33 acre-feet of precipitation – in areas with way less than 10 inches of annual precipitation.

While we’re talking numbers, the 14.8 maf at Lee Ferry is not an actual measure of water flowing past the division point, but an estimate of what the flow there would have been if there were no human water consumers upstream. There are of course hundreds of farmers and ranchers upstream as well as some substantial cities and lots of towns in the three major tributaries of the Colorado River mainstem: the Green, the Colorado-Gunnison confluence, and the San Juan. Towns and cities can estimate their consumption fairly accurately (especially the half a million acre-feet that go through tunnels to the Front Range metropolis. But more than 80 percent of Upper Basin consumptive use is agriculture, and the largest portion of that is hay production in mountain valleys not easily adapted to modern large scale irrigation technology (even if the small ranches could afford it). Flood irrigation is the default process; and how much water gets used in that makes the ag consumption figures a really rough guesstimate.

I realize that this may be more attention to numbers than you like – where’s the ‘romance of the Colorado River’ in all this bean-counting? Maybe that’s the way of romance, its seductive wile: we are lured in by an irresistible grand romantic vision – conquering the wild river! Measuring ourselves against Nature! Teaching Nature to stand in and push for us rather than cut and run! And then, in what should be the victory lap, you find yourself anxiously counting and squabbling over cupfuls of acre-feet here that are needed there and vice versa.

Well, let it stand for the moment that a 25 percent efficiency is a good enough estimate for the Colorado River’s water-producing region – that above the 8,000-foot elevation, one acre-foot in every four escapes the sublimation, evaporation and transpiration of the sun and wind, to flow out into the water-consuming deserts. It might actually be closer to 33 percent, one acre-foot in every three; but it is obviously a number that would vary annually anyway, with the number of sunny versus snowy days through the winter, rapidity of the melt, and a hatful of other ecosystemic variables.

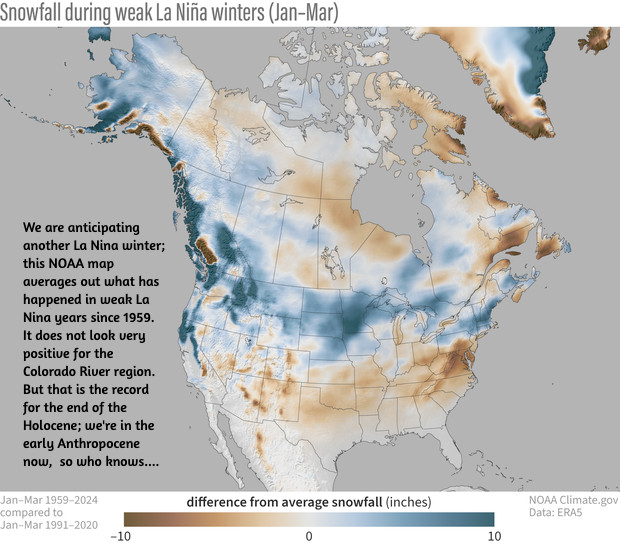

The question for the water-consuming region then – aware as we ought to be, that we are losing in our changing climate 5-6 percent of our river’s water for every one degree F increase in average temperature – is whether there might be better management strategies for the Headwaters that would improve that ratio even just a little, to help compensate for coming losses…. And don’t be thinking that maybe what we need is less management, not more (more wilderness!). If we are going to keep adding more people to this planet, we are going to need better management everywhere – maybe not more, definitely not less, but certainly better.

We can say, with some confidence, that about the only part of the Headwaters where we have significant management options is the broad band of forests and grasslands ringing the Southern Rockies above the 8,000-foot elevation where most of the river region’s precipitation falls. These forests and grasslands occupy most of the water-producing region below the alpine tundra where the sun and wind rule uncontested, and above where the high deserts begin below the 8,000-foot elevation. Those forests – the subalpine spruce-fir forest and the montane pine forest (splashes of aspen everywhere in both) – are almost all public lands, designated National Forests, managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

The 1897 ‘Organic Act’ that turned existing ‘Forest Reserves’ into National Forests, and created the Forest Service to ‘improve and protect’ them, gave a broad overview of the National Forest mission:

‘No public forest reservation shall be established, except to improve and protect the forest within the reservation, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States.’

The use of the conjunctions ‘or’ and ‘and’ there indicate that this law might have been written by a lawyer trying to hedge something by writing like a lawyer. Does the ‘or’ indicate a choice had to be made between the two ‘use’ clauses and ‘improving and protecting’ the reserved forest? And why the negative-sounding start: ‘No public forest reservation shall be established, except…’?

We need to remember that 1897 was Very Early Anthropocene (1850s-1950s): we were simultaneously trying to do two things. On the one hand, we were developing increasingly effective and efficient fossil-fueled methods for vacuuming up the resources of the continent and turning them into production infrastructure and consumer goods. The assault on the forests for timber to turn to lumber to feed the insatiable call for more houses got seriously industrialized with steam-powered sawmills and railroads to haul the forest products quickly in great volume.

But on the other hand, we were becoming ‘woke’ to the consequences of these resource-mining activities. The 19th century equivalent to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 was Man and Nature, published in 1864 by the early conservationist George Perkins Marsh. Marsh laid out in plain language the consequences of timber-mining and grass-mining, as well as the more conventional mining of other valued resources. Clogging and gullying of the rivers and streams were the worst consequences of these practices, choked with soil and debris washed off the denuded slopes – which also diminished the ability of the forests and grasslands to grow again. The farmable floodplains were devastated by larger and more violent spring floods.

It’s easy but not very accurate to say the one hand did not know what the other hand knew; but anyone dependent on the rivers for water knew the unpaid cost of all their houses and barns. It was, however, knowledge for them like the knowledge of the climate crisis is for us today: knowledge to be acknowledged only through the five-step process of accepting what we don’t want to accept: denial, anger, negotiation, depression and finally, acceptance.

This probably explains the negative beginning the Forest Service mission statement – ‘No public forest reservation shall be established’ – except when we think we have to. Goddam right! This the people’s land, not the government’s! Ours to put to beneficial use! But – yeah. We’ve got to do something about the mess running of the mountains into the rivers…. But can’t it wait till we’ve converted a little more of it into wealth?

Well, that’s a good place to stop for now. Denial and anger have a long history in American exceptionalism.

Next time – a closer look at the forests and water production.

Pingback: Romancing the River: Forging on in the Era of Fear and Loathing — George Sibley (SibleysRivers.com) #ColoradoRiver #COriver – Coyote Gulch

Your perspective is this piece resonates with me

I’m so glad that a friend of mine ( Len Aitken ) sent me your “Sibley’s Rivers”. Keep up the great work and keep going with the flow!

Right on, as usual George! Again Growth (‘more’) is the unseen, unthought-about, gremlin behind the whole, unsustainable mess with this water—-and virtually all else too, what with 90 percent reduction of animal numbers already, etc.

PS. I;ll deliver your copy of the book Eventually!. k