We’re in a bit of a holding pattern along the Colorado River today, at least in the Upper Basin: on the one hand, waiting for the Bureau of Reclamation to weigh the options for big cuts in Lower Basin use; and on the other hand, seeing the Lower Basin states trying to come up with a less painful set of big cuts to impose on themselves over three years, taking advantage of the big snow year that relieves a little (but just a little!) of the immediate pressure.

At any rate, it’s an opportunity for me to step back a step and try to restore something of the perspective with which I started these posts – ‘learning to live in the Anthropocene.’ I’ve been calling the posts ‘Romancing the River,’ wanting to work in the spirit of Frederick Dellenbaugh in his book The Romance of the Colorado River: making the story of the First River of the Anthropocene something to engage in rather than deny. But the stories keep getting lost in the avalanches of mostly dispiriting details coming down these days….

So anyway, today – an unremembered part of the story of Glen Canyon Dam. Last post, we explored the structure of the dam itself, a good solid Early Anthropocene structure. But today I want to explore the infrastructure of the dam. As with most dams, what you can see is not the whole thing, even physically. To get a firm foundation on bedrock for ten million tons of concrete, the builders had to dig out more than a hundred feet of rock, rubble and sand from the natural streambed. That hundred feet of dam below the streambed is the physical infrastructure of the dam.

But even before that digging-down could begin, a political, economic, legal and philosophical infrastructure had be cobbled together on which to erect the physical structure. Recent articles about the river and its troubles that try to offer any river history at all tend to give credit (or blame) for the dam to a large mass of ego and bluster, Floyd Dominy, but he was just the Reclamation Commissioner when the dam was legislated, a guy who wanted to build dams as big as his ego. He built the structure, but he didn’t assemble the legal and political infrastructure that enabled it.

The larger story of Glen Canyon Dam’s infrastructure is mostly, but not entirely, a story of the Old West – a story of the most serious attempt to achieve a working truce between the Old West and the New West. And for those with my tendency toward an iconoclastic interpretation of history, it was one of the final episodes (thus far anyway) in America’s semi-civil westward war between the advance of the well-defined and well-funded Industrial Revolution and the retreat of a vaguely defined agrarian counter-revolution. For a review of that semi-civil war, go to ‘Westward the Curse of Empire,’ April 4, 2022.

When we talk about the Old West and the New West, we are talking about two very different cultures. Most (over)simply, we can say that the Old West is the west to which people went to live and make a living developing and marketing the natural resources of the West; and the New West is the west where people who live in the urban-industrial realm go to play, to ‘recreate’ themselves among the natural wonders and magnificent scale of the West.

It is useful to make a further distinction about the Old West: it was populated by ‘settlers’ and ‘unsettlers’: the unsettlers usually arrived first, the human equivalent of a plague of locusts with a mining mentality (mining gold and silver, other metals, old-growth timber and grass) – a drive to get there first, get the goods, and get rich. The settlers, on the other hand, came to farm or ranch with the intention of staying and making a life, settling down, homesteading. Some of the farmers tended to be soil miners, but the ones who stayed were true agrarians, the counterrevolutionaries to the industrial revolutionaries.

People of course do come to live in the New West too, not just to visit: they are usually either relatively well-off people retiring, or professionals working remotely with incomes from elsewhere, or they are mendicant people like I was sixty years ago (relatively poor, mostly by choice) who work for the recreation industries set up for the people who come to play, in exchange for getting to live and play themselves among the natural wonders of the West.

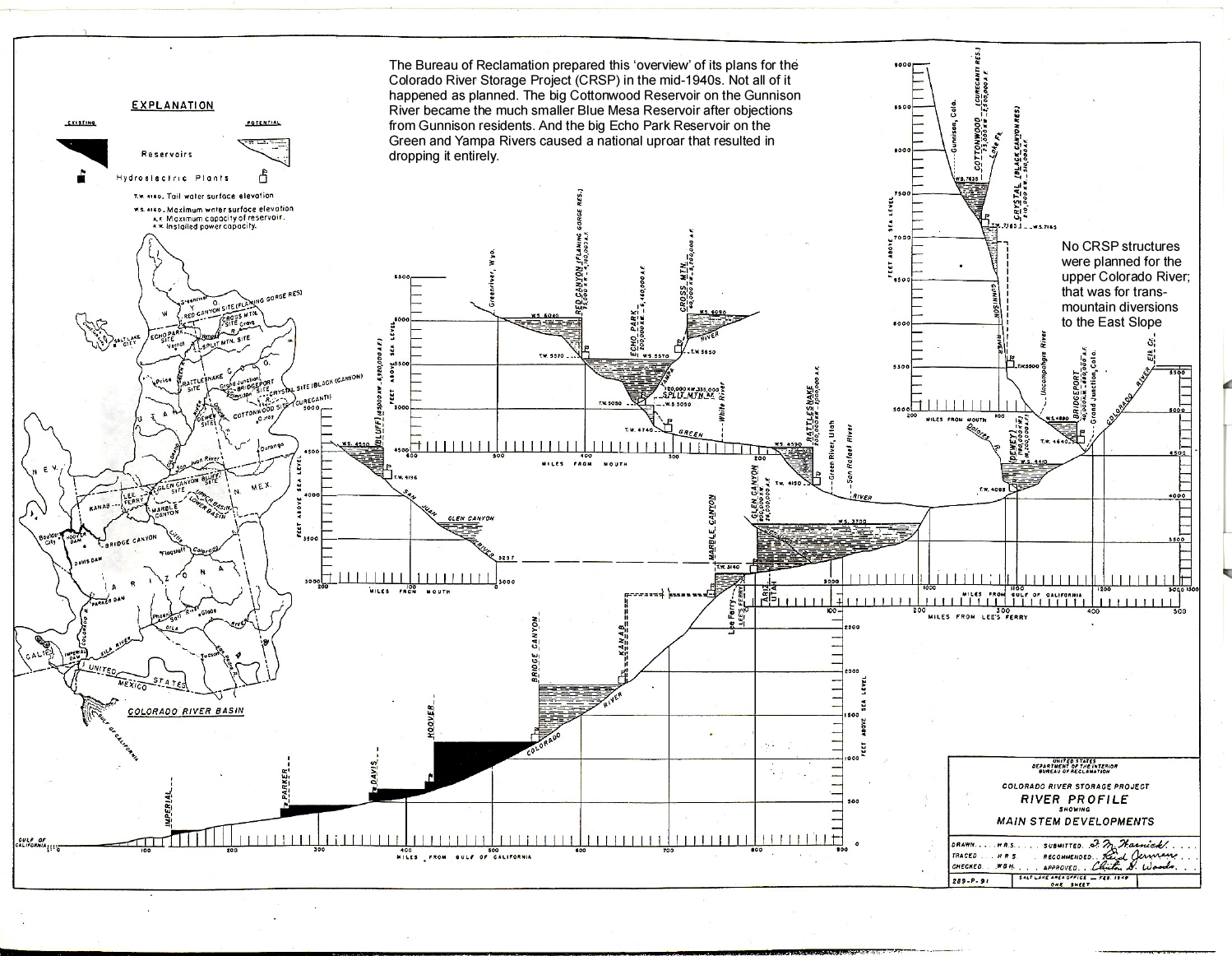

The story of Glen Canyon Dam, and the counterrevolutionary effort to co-opt it, began in the years immediately following World War II. The Lower Colorado River Basin had already been transformed into a desert empire through the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project, completed just in time for Southern California to grow explosively through the war effort. The four Upper Basin states figured that they would get their day after World War II. And in 1946 the Bureau – eager to follow the creation of Hoover Dam and the desert empire with more river miracles – came out with a pamphlet: ‘The Colorado River: A Natural Menace Becomes a National Resource.’ In it the engineers presented a smogasbord of 88 possible projects, large and small, all in the four states of the Upper Colorado Basin. They cautioned that there would not be enough water for all 88, so there must be some choosing.

The principal architect for the legal, political and economic infrastructure underlying what came to be the Colorado River Storage Project was no larger-than-life figure like Dominy, but an unprepossessing Congressman, Wayne Aspinall, from Colorado’s West Slope and the river’s largest headwaters catchments. Aspinall did not stand out in a crowd, but he was savvy, and absolutely committed to the Old West as an economy of working people engaged in the production of resources needed in the larger society – and with a deep love for irrigated agriculture, having grown up with his father’s peach orchard in the Grand Valley after the Bureau’s highline canal brought them water.

He was a Democrat, an unlikely representative from one of Colorado’s most conservative districts, but he began his political career in the late 1920s as a common sense alternative to the mess the Ku Klux Klan had made everywhere in Colorado, and he kept getting re-elected to state, then national offices because he got things done.

When the West Slope sent him to Washington in 1948, he got appointed to the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, mastered the arcane procedures of the House, and as the district kept returning him to office, he gradually ascended to the chair of that committee, which gave him a lot of power over the budget and operations of the Interior Department and its Bureau of Reclamation. He exercised that power so vigorously and, in the opinion of many of his colleagues, so arbitrarily, that House committee rules were changed after he left, to diminish the power of chairs who took the time to learn the rules well enough to manipulate them.

He also knew which way the tide was running in America. The 1920 census for the first time showed more people living in the cities than in the rural areas, and by the end of World War II, that imbalance was accelerating. (‘How ya gonna keep’em down on the farm, after they’ve seen Paree?’) His Old West constituency was being diluted by newcomers aghast at learning a few eggs had been broken in making the omelet they took for granted. The cities they came from were also needing more water, and Aspinall was often caught between constituents angry about yet another transmountain diversion, and east-slope movers and shakers angry about what he could not deny but could often delay.

Nonetheless, his Old West constituents knew where his heart lay, and returned him to Congress 12 times. That might have continued indefinitely, but his own Democrat party outgrew its working-class roots, became a big city party, and gerrymandered him into a mostly urban district where he could not win; he was ‘primaried out’ in 1972. It was probably time; he had become a lightning rod for the early naive-environmentalist movement, and being aligned with that movement myself, I felt naively righteous in voting against him. I still think it was the right thing to do then; he had become increasingly reactionary and defensive, at least as he was being reported in the newspapers. But given what I’ve learned about him since, and my ambiguous feelings about the New West that has replaced the Old West, and about the staggering march of American history in general – I wish I had cast that vote a little more humbly.

In the 1950s, however, Aspinall was just hitting his stride when the Bureau was ready to finish remaking the First River of the Anthropocene, and he jumped on the opportunity to do something big and (he hoped) enduring for the West he and his constituents believed in. More than any other single person, he laid the infrastructure for the Colorado River Storage Project. For better or worse.

The Colorado River Storage Project had to first be a really serious storage project, to assuage Upper Basin water users’ fears of a Compact call, which they thought would come even if nature, not human overuse, caused a shortfall in Lower Basin deliveries. Another time we will take a look at the Upper Basin Compact created in 1948, and the knots the four states tied themselves into, due to their Caliphobia. So the first charge to the Bureau was to build some big ‘holdover’ reservoirs on the scale of Mead Reservoir – dams capable of storing at least two years of inflow.

But the Bureau and Aspinall also wanted big hydropower units in those dams – ‘humming the tunes of endless wealth,’ as a bit of precious Bureau prosody put it. ‘Cash register dams’ was a more prosaic nickname for the big power-generating dams: they wanted the wealth so generated to be applied not only to paying off the big dams, but also to pay for a lot of smaller dams in the higher country.

The biggest problem farmers and ranchers in the arid lands had in irrigating from a desert river fed primarily by snowmelt was the erratic flows – snowmelt floods early in the irrigating season and then almost no water in the late summer when it was most needed. Storage to even out the flows was the key, and storage was expensive. Every community of farmers could go out after harvest with shovels, black powder and mule scrapers, and dig canals to move water, but water storage required materials and equipment they couldn’t afford. Every irrigation district had sketch plans for dams and reservoirs, but for small communities, the Bureau’s cost-benefit analyses for dam repayment were impossible.

But – if a general fund for a big multi-unit project could be created, with power revenues pouring into it, and some small storage projects drawing on it, with cost-benefit analysis calculated for the whole multi-unit project, then the big dams could carry the otherwise unaffordable little dams…. Glen Canyon Dam would (‘twas hoped) assure that the industrial revolution’s desert empire got its water – but it would also provide storage for the counterrevolutionaries’ ‘headwaters republics.’ Win-win.

And that was essentially the Colorado River Storage Project Aspinall and his collaborators in the Upper Basin put together. They started in 1950 with a bill calling for nine big holdover dams and reservoirs, and a couple dozen ‘participating projects’ (the smaller storage dams for the local communities). By the time they finally got the project through Congress in 1956, they were down to three actual holdover dams (Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado mainstem and Flaming Gorge on the Green River, both with full power generating units, and Navajo Dam on the San Juan with no power unit), the Curecanti unit of three dams on the Gunnison that was primarily for power production, and eleven ‘participating projects’ to be partially paid for from the power revenues – and another two dozen potential participating projects for further study.

And because Aspinall knew the New West was coming, like it or not, the Act included a requirement that every unit would include recreational facilities.

Did it work out as planned? Yes and no. The ‘cash register’ dams were all built, and facilitated the building of around a dozen of the small ‘participating projects.’ My great-grandparents would have been glad for the dam built on the North Fork of the Gunnison River above Paonia, the erratic river whose spring floods had forced them to move their house to higher ground. But they had sold the homestead by the time the dam was built because none of their offspring wanted to contend with the erratic water supply.

By the late 1960s, however, the nation had grown tired of building (and paying for) western water projects, and NEPA and the advent of the Environmental Impact Study after 1970 made even small water projects problematic. The last project done under CRSP auspices was an Animas-LaPlata project originally intended to help the Ute Indians develop agricultural lands, but it got so scaled down that it was not much use to anyone.

By the turn of the century, ‘reclamation’ was more likely to be interpreted as work to reclaim and restore land and waterways damaged by the collateral debris that the Old West’s heavier industrial unsettlement left behind. Then in the 1980s a large portion of the power revenue from the big holdover dams was diverted from further CRSP counterrevolutionary structures, to an all-out effort to restore four endangered fish species that, back in the 1970s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tried to kill off by poisoning the Green River. Mistakes have been made, and visions and dreams got carried out with the debris.

The recreation industries, and the accompanying real estate and construction industries, have pretty much overrun and occupied Aspinall’s would-be agrarian republic; but there are, nonetheless, still places in the West where small farms and ranches hang on, some of them ‘heritage cultures’ passed on through families predating CRSP, some of them new and serious about growing local food – and many of them served by CRSP facilities generated by Glen Canyon Dam. But the agrarian philosophy and vision they represent is largely unarticulated in the mainstream culture; I believe, however, that a careful and potentially difficult interrogation of a large number of rural MAGA supporters would reveal that a virulent form of the agrarian counterrevolution still lives, mute but mad, in a twisted variant of unarticulated hope.

Just call it all another story in the romance of the Colorado River – the story of how Glen Canyon Dam was, for a time, put in service to another America.

Thanks for keeping me up to speed and throwing some light, George, on a fast ever changing, complicated and maddening narrative.

Onward thru the smoke and mirrors, the fogs and the talking heads.

Vince

I feel there may still be too many “pure” environmentalist who want a world untouched by humans, not realizing we too are part of the environment. On the other hand, the arrogance and hubris, of Floyd Dominy in particular, helped create the mess we now find ourselves in. Aspinall, on the other hand, was devoted to his constituents and, in many ways, to the river.

Thanks, Perfesser. I have learned almost more than I want to know, reading your excellent and comprehensive chapters. I bet you and I both are happy we turned out to be “settlers”.

A great review of our state’s 20th century history. One comment is to wonder how we ever make progress on big civic endeavors with so many conflicting, competing interests?

So now, as we know, with the deadline only a few days away, the three Lower Basin states have come to an agreement. Hooray!

One response to your comment would be to look to Wayne Aspinall’s example. Despite his reputation for stubbornness – well-earned – he was always trying to find the path through the issues that everyone could accept as a reasonable way. He was representing a minority that wanted the status quo for the West, while having to accommodate the mainstream juggernaut that wanted the West to be a natural vacation paradise…. The West is better off today for the studies he insisted on, which to be sure were partly a delaying tactic, but which helped give things like the Wilderness Act a more solid foundation without entirely alienating either his constituents or the wilderness advocates. He insisted on a big recreational-use study before he would let the Wilderness Act out of committee, and that led in a roundabout way to the Land & Water Conservation Fund, part of the Aspinall legacy. There aren’t many legislators today with his attention to both the big picture and the details, and his capacity for compromising his own values for what he perceived as the greater good for both the greater number and the lesser number…. Not easy.

Thank you George.

You mention that the last project done under CRSP auspices was the Animas-La Plata. However, the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project, which is still under construction, was authorized in P.L. 111-11 as a CRSP project.

Thank you, Paul, for that information. I was referencing the projects named in the original CRSP Act of 1956, and wasn’t aware that other projects have been taken under the wing of CRSP…. It’s probably worth noting today that the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project, listed in the original projects to be studied, was begun at the same time as the San Juan-Chama Project but is still not completely finished…. – G