‘Fiddling while Rome burns’ – that’s what the Roman emperor Nero is remembered for, practicing on his fiddle while mobs tore up the city. In Ortega’s memorable phrase: responding to the lack of bread by burning down the bakery.

But – ‘fiddling while Rome burns’: I often feel like that’s my life these days. We are facing two situations that are called ‘existential’ because they are deeply impacting the way we live – even if we live on as a species. One of the two is immediate, this year, choosing whether we will continue as a more or less free and open democratic society, or will submit ourselves to an authoritarian regime under a malignant narcissist. And the other situation, longer term but more inevitable: whether we will choose to drastically change some foundational cultural systems that are making the planet increasingly uninhabitable for us as a species.

This being where we are – what am I doing about it? There seems to be little that America’s favorite character, the rugged individualist, can do. In the more immediate situation, one can try to argue for a fact-based reality, but history shows that, once the pentup rage of those who want to blame their unhappy lives on others is out of the bag, there’s no putting it back; it has to run its course. The beast is among us.

And the other thing, the changes we’ve unconsciously wrought on our planet – we all seem to be daunted, even numbed, by the challenge of converting a civilization running on carbon fuels to – running on something else. I think most about these things when I wake up at 2:00 in the morning when there’s nothing to do but listen to the echo of Nero’s fiddle.

I also wonder then, whether writing about, and inviting you to think about, the Colorado River and its melodramas is just more ‘fiddling while Rome burns.’ But I am not being facetious when I call the Colorado River ‘the First River of the Anthropocene’; our works up and down the river are one of our most comprehensive and concentrated efforts to rearrange the planet to better meet our needs. And so doing (not just on this river), we have contributed significantly, if mostly unconsciously, to reducing the volume of water in the Colorado River to about two-thirds what it was a century ago when we began reconstructing it.

We have presented ourselves with a huge challenge in adapting to a climate that we ourselves have inadvertently shifted toward the warmer and drier: how do we manage our shrinking manmade river to water and feed a relentlessly growing population? And if we cannot work out some sustainable systems for this, on a relatively modest river in a defined region, how can we hope to work it out on a global scale?

So – back to the river. Where an effort is currently underway to come up with management strategies for the river after 2026 when the most recent set of bandaids on the ‘Law of the River,’ the ‘Interim Guidelines,’ expires. Interim Guidelines that required a couple additional interim bandaids just to stagger through to 2026.

One of the questions no one seems to want to ask or try to answer is whether we are going to just add more links to the ‘Law of the River,’ our Marley’s Chain, or whether we are going to go back to basics with a new set of guidelines and regulations, laws and limitations to fit what is really a ‘new river.’ ‘Marley’s Chain’: the huge clanking chain hung with ledger books and moneybags that Ebenezer Scrooge’s former partner Jacob Marley had to drag through eternity – that seems like an apt analogy to the ever-evolving Law of the River, but nothing says we have to drag it through eternity.

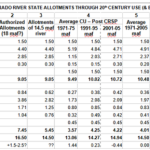

There are four ‘thinking like a river’ arguments for relegating the existing Compact and Law of the River to the archives of ‘Mistakes to Learn From Rather than Build On.’ The first argument would be the fact I’ve already noted: that we are working with what is in effect a new river. As the 2023 study by Jack Schmidt and Eric Kuhn laid out, the flow of the Colorado River thus far in the 21st century averages a well-measured 12.5 million acre-feet (maf), compared to flows averaging a roughly estimated 18 maf in the early 20th century – the river on which the Colorado River Compact and subsequent Law of the River elements were based. Hydrologists project that 12.5 maf is the river’s future – at best. The structures added to control, store and redirect the river through the last two-thirds of the 20th century disguised to some extent the fact that it was a diminishing river, but by the turn of the century, and the dry decades following, the fact that we were dealing with a new, smaller river could no longer be disguised by moving water around in the reservoirs (the Interim Guidelines)..

A second argument for why we need to start over on management strategies is the fact that the Colorado River Compact and other early Law of the River components were written by and for just the seven Colorado River states. There are now 31 nations in addition to the seven states wanting inclusion in developing future management strategies. The 31 nations are the Republic of Mexico and 30 federally recognized First People nations overlaid on the seven states – some very small, but most of them with unfulfilled legal water claims. Somehow the seven states neglected to hang on their Marley’s Chain the 1908 Supreme Court decision granting First Peoples constrained to reservations enough water to become civilized farmers, with decrees dated from the creation of the reservation (‘Winters doctrine’). The 30 First People nations are determined they will not be left out in future river planning. The Compact cannot be stretched to cover that.

The third argument for starting over is more complicated, but is also more foundational to today’s challenges: the need to examine and maybe limit the real foundational law of the river – not the Compact but the prior appropriation doctrine. When representatives from the seven states gathered in Washington in 1922 to develop a Colorado River Compact, their main objective was to corral and tame the power of the prior appropriation doctrine on the interstate level, wanting to preempt it with a seven-way division for the use of the river’s water. This story is told in the January transcripts of the Compact commission meetings. A good read if you’ve got the January blahs.

The right to use water consumptively in all seven states was from the start determined by prior appropriation: first come, first served. This was a grassroots ‘common law’ that worked well enough for resolving squabbles among rugged American individualists on local streams. The states then worked out intrastate systems for determining multi-stream senior water rights as streams came together in confluence. Pre-computer record keeping for this was hell, but the state engineer offices and courts managed it.

But what about interstate rivers like the Colorado, flowing through or between seven ‘appropriation’ states? The logic of prior appropriations decreed that the states would have to honor each other’s prior appropriations – affirmed in 1922 by the Supreme Court in an interstate challenge between Wyoming and Colorado. But the six states upstream from California looked at how fast Southern California was growing – and appropriating Colorado River water to grow on – and feared there might be no water left for their people to appropriate when they got up to speed.

So their intent on gathering as a compact commission in 1922 was to establish a seven-way division of the river’s water, setting limits on each state’s future development of water that would override the appropriation doctrine between states. But that proved impossible; the seven had no real data on their future needs, just ebullient Early Anthropocene dreams – and their cumulative dreams added up to half again more water than even the 18-maf river would have provided. No one wanted to yield, and they almost gave up on the compact idea in frustration. The federal representative and commission chair Herbert Hoover persuaded them to stay with it – reminding them that there would be no federal money for development of the river, to control and store its two-month floods, until the seven states agreed on the use of the developed water.

The two-basin division of the river they finally came up with for the compact did not generate agreement among all seven states; Arizona refused to ratify it – anticipating the kind of interstate appropriation conflict that arose in 2022, the centennial year of the Compact, when California played the seniority card against the other six states in the effort to share out the massive 2-maf cuts ‘demanded’ by the Bureau of Reclamation to salvage the river’s storage system.

The Compact’s decreed 7.5 maf ‘delivery obligation’ on the Upper Basin for the Lower Basin, regardless of water conditions, was also a growing source of tension between the two basins, having been interpreted as a Lower Basin appropriation by another name. The Compact’s only real achievement was satisfying Congress that there was a sort of agreement among at least six of the seven states, which Congress decided was enough to go ahead with the Boulder Canyon Project (Hoover Dam and the Imperial Valley delivery structures).

Evidence that we are right back where we were in 1922 was directly stated in the 2022 meeting of the Colorado Water Users Association in Las Vegas, when Tom Buschatzke, Director of Arizona’s Department of Water Resources, declared, ‘The single biggest roadblock to solving the problem of stabilizing the river is the priority system.’ And John Entsminger, General Manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, added a warning: ‘If 27 million Americans don’t have water, then those [senior appropriation] laws will not be followed.’

I will hasten – hasten to say that I do not advocate repealing appropriation law in the arid West; I don’t have a death wish, and anyway that would be like cutting off the hand to cure a hangnail. I don’t think Buschatzke and Entsminger want the law repealed either.

But there are some things about the prior appropriation doctrine and its limitations that we need to acknowledge, and figure out how to address, with fairness to those senior users who have been using the river’s water for generations, but also for juniors whose uses are every bit as valuable for the larger society, and sometimes moreso. The waters of the Colorado River are already over-appropriated on most reaches of the river and its tributaries – and the supply of water in the river is diminishing as the planet warms. The seven-state division of the river is effectively accomplished, to no one’s apparent satisfaction. The use and distribution of a diminishing resource may need to be administered with a larger vision than only ‘first come first served.’

But that brings me to my fourth argument for archiving the Colorado River Compact and its Marley’s Chain, and starting fresh with the river we’ve made from the river we were given. This is more of a ‘thinking like a river’ argument. A rancher I know in the Gunnison River valley said it’s every rancher’s dream to turn his watershed into a catchment basin. Meaning it would be nice to catch all the water and put it all to work so none was shed unused into the watershed. Fortunately, catchment basins are too leaky to keep all the water from shedding, underground if not on the surface, so the river keeps flowing. The goal of putting as much water as possible to work nurturing life is honorable enough, but there’s a point where the water user has to let his thinking like a water user yield to thinking like the river that runs through his life to the lives of many others

I think of this when I hear Colorado’s, or Arizona’s, or the Navajo’s, or whoever’s representative at the big future planning table, telling the folks back home that they are fighting hard for their state’s or nation’s share of the river, whatever it might be…. But one might hope that, at the big table, they are all thinking more like the river than thinking like Coloradans or Arizonans or Navajos, the ‘first come first served’ thinking that resulted in both the creation and the undoing of the well-intentioned Compact and its Marley’s Chain of amends, add-ons, course corrections and interim bandaids.

Next time, we will tread carefully into and around the prior appropriation doctrine, a big component in the foundation of the Anthropocene.

As I was getting wrapped up in Marley ‘s chain, I was waiting for Scrooge’s “Bah, humbug.” It didn’t appear, but perhaps we will have an epiphany similar to his by the end of the story.

If we insist on dragging our ‘Marley’s Chain’ into eternity – it’ll be a humbug, for sure….

Sadly, all water law and regulation in this country needs updating, not just our prior appropriation doctrine. But as long as we cling to the wrong history, politically too, we are probably doomed. Something like 30 years ago Rolllie Fischer told me he thought the Compact would, and should, be reopened. It’s a miracle it has not and a good thing for us as we no know so much more how other states mostly do an even worse job of managing water than we do in Colorado. 30 years ago we thought California had a management edge, silly us. Your question really is, has homo sapiens outlasted its potential?

When it comes to cultural evolution (as opposed to natural evolution), I’m a Lamarckian (as opposed to Darwinian): homo sapiens, thinking man, ‘evolves’ solutions to survive challenges and exploit opportunities…. This has worked best with technical/technological solutions to natural challenges; we’ve not done so well ‘evolving’ social and economic solutions to cultural challenges that can’t be managed through more technology. If we can’t improve in that area – then, yes, we will have outlived our potential….

An excellent column with a clear-headed attempt at a solution that has us thinking like a river not as dinosaurs trying to protect ourselves from the climate meteor with our teeth bared and insufficient tools.

Of course I understand not calling for an end to prior appropriation. But clearly that principle doesn’t work when applied to the river as a whole. And difficult as it will be, changing the Law of the River to the new reality River is going to have to happen — either working together or with everyone suing each other in court.

While we will never be able to do away entirely with prior appropriation law, we can – probably must – set some limits on what it applies to…. There has to be some protection for downstream users being preempted by upstream junior users. But on many, maybe most (but not all) higher tributaries, farmers and ranchers work out ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ to share out what water there is in a bad year, irrespective of seniority; water users who have been neighbors for two or three generations don’t place calls on each other (although there are deteriorated situations where they do that). This collaborative process could be encouraged intrastate through ‘carrots.’ But appropriation law should be applied only in situations among users; it should not be applied in larger hydrologic situations like diminished flows or system losses that should rightly be shared equitably among all users, and larger users should bear a larger part of that burden. We can’t eliminate the body of law, but we can limit – just through common sense and a sense of overall fairness – what it applies to.

A water amateur, I would add a phrase to the first paragraph’s second sentence so that it reads: “This was a grassroots ‘common law’ that worked well enough for resolving squabbles among rugged American individualists on local streams [in well-watered country]. It’s the “well-watered country” part that makes the compact, and any tinkering around the edges of it, largely a wish, or a fond hope, rather than any sort of reasoned goal, much less a plan. The Colorado’s water is a scarce resource that seems likely to diminish further at the same time demand for it is on the increase. The physics at work changing the climate doesn’t care that the Navajo deserve, and are entitled to, significant water resources because, after all, even under the doctrine of prior appropriations, they were here first, and should have the first claim on that scarce resource.

Should the climate of the 7 Compact signatories continue to warm and dry out, and the Colorado River basin turn into something like inland Algeria, Libya, the Sudan, etc., ethics, fairness, and law will have a very hard time competing against the industrial age’s primary product and pollutant: money.

The financialization of water is already underway…. The willingness of the First Peoples to negotiate in a settlement process, working with the rest of the water users tapping ‘the commons’ to get a reasonable share of water to use, is an exemplary (and realistic) way of working around the appropriation doctrine.

Beautiful introduction! (plus the rest too). This is why I cited George in my new book.

By the way, George, I just received a new, privately published book by Fred Graham-Yooll called “Overpopulation, Earth’s Destruction, and the Fix”. It is rather poorly written but contains some excellent data on the soll and water situations around the world. I’ll bring it with me when I come down to Gunnison to discuss it with you. luv ken

Thanks for the reference, Ken. See you at Mocha’s this summer?