I really like the AI image above, created by a couple creatives at American Whitewater, Scott Harding and Kestrel Kunz. for a presentation at the Colorado River Water Users Association convention in January. It shows ‘the people who run the river’ running the river. But if you have ever been in that whitewater situation, you know that the river is really in charge; you run the river on the river’s terms. The guy standing up in the back of the boat is in charge of the boat, giving the others in the boat commands like ‘Five forward (strokes of the oars) on the right!’ ‘Two back on the left!’ ‘Everybody three forward!’ – trying to keep the boat on a ‘line’ he or she perceives through the rocks of the rapids. Thinking like the river to run the river.

We can draw some obvious analogies to Colorado River management – as Scott and Kestrel do in the picture above of the people in suits who ‘run the river.’ But the analogy breaks down quickly around the fact that they are all – we are all – in a boat without a boatman. Instead of all those who are running the river following directions from one person who is using his past experience to pick a line through the rocky places – ‘A 100,000 acre-feet to the Navajo!’ ‘Everybody cut 10 percent!’ – we are doing it through committees, groups, divisions, maybe some factions by James Madison’s classic definition (groups whose acts are ‘adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community’).

In this case we have the Lower Colorado River Basin on one side of the raft, the Upper Basin on the other side; they are each forming a perspective on the rocky places ahead and describing a line through them that requires issuing some advice or orders to those with oars on both sides of the boat about forward or backward actions, resulting mostly in quite a lot of noise, in which the intelligence from both sides gets rendered unintelligible….

There are various possible resolutions to such a situation. Some will say we have to have a boatman, one person to whom we will all listen and for whom we will all act obediently. On the real river, boatmen have to earn their right to be that person through experience. But on the metaphorical boat on the allegorical river, it is not always easy to select a boatman to get through the hard places because – what experience counts? What background is necessary and sufficient? What demonstrable skills? And there is always a loud narcissist in the boat who trumps the discourse by trumpeting that he or she is ‘the one, the only one that can get you through this’; those ‘strongmen’ appeal to many in the boat, when the better idea might be to just pull off the river before the hard place, unpack the lunch along with the situation, and work out a plan democratically before plunging in….

That is, in a sense, what is going on today in the Colorado River Region (natural basin plus out-of-basin extensions). Everyone knows that there are hard places as we all try to face up to some hard realities the river is imposing on us (at least partly because of hard things we have imposed on the river).

After a feel-good conference this January of the Colorado River Water Users Association, the seven basin states and representatives from the basin’s 30 First People nations sat down to work out a new set of ‘Interim Guidelines’ for an ‘interim’ beginning in 2027, to replace the tattered, battered and bandaged Interim Guidelines that the Colorado River waterworks have been working off of since 2007 with a ‘use by’ date of 2026.

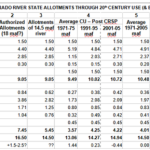

That larger gathering hung together for several sessions; then, as I understand it, the three Lower Basin states withdrew to figure out how to handle a ‘structural deficit’ that is about one-fourth of their 8.5 million acre-feet (maf) allotment from the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which deficit they finally conceded was their responsibility – just their concession being a major step forward. The ‘other side of the boat,’ the Upper Basin states, began meeting on their own.

Now, just this week, the Basins have each submitted draft plans for post-2026 river management to the Bureau of Reclamation – the Upper Basin Tuesday March 4, and the Lower Basin Wednesday March 5.

I wanted to get something online this same week about this so my faithful readers would not think that I am asleep at the wheel or lost in river history, but there is no way to even obtain and read these plans, let alone try to make sense of them together, before my webmeister’s Friday deadline. So I’ll be back with you either next week or the week following with my two-bits on what’s going on.

But we can do a little backgrounding now. The ‘structural deficit’ the Lower Basin has finally conceded it must deal with is a substantial omission not covered in either the 1922 Compact nor in the subsequent elements of the Law of the River. It is, first, a compilation of all the ‘system losses’ from evaporation, bank storage, riparian vegetation, et cetera, from Mead Reservoir to the Mexico border – estimated by the Bureau of Reclamation to be around 1.3 million acre-feet (maf).

It also includes, second, up to 750,000 acre-feet that is the Lower Basin’s share of the Mexican obligation. Responsibility for these has been dismissed by the Lower Basin as being covered by ‘surplus flows’ – anything over the 7.5 maf the Upper Basin is committed to send through the canyons. For most of the 20th century this surplus was legitimate: water not yet being used by the Upper Basin and the Central Arizona Project, plus the occasional blessings of big water years. But for roughly the last quarter century that surplus has largely been a paper accounting; the ‘structural deficit’ that emerged was basically the Bureau drawing down storage in a time of drought to keep nurturing the ‘surplus’ fiction while praying for snow.

The 2007 Interim Guidelines were created to try to address this problem – but without really addressing it. The Guidelines were kind of a shell game, ‘balancing’ the contents of Mead and Powell reservoirs, with tipping points in the storage of both that would precipitate shortages being imposed on the Lower Basin states – but doing obeisance to California’s senior water rights by shorting the other two states first and most. And they continued releasing the substantial ‘structural deficit’ water to not force the Lower Basin states cut back on their own.

These ineffective guidelines led to the Bureau’s realization in 2022 – the centennial year of the Compact – that they might be two or three years from losing the storage in the big reservoirs entirely for much of the year, resulting in the quasi-panicky call to the seven states to cut consumption within a year by 2-4 maf.

I will not go through again all the plans and counter-plans that were proposed and analyzed to answer the Bureau’s call, but do want to call attention to the fact that the situation did revive a spate of ‘Caliphobia,’ when six of the Basin states prepared a plan for a proportionate sharing among the Lower Basin states of cuts that amounted to the structural deficit, but California would only participate if its substantial senior water rights were honored, with the other two states bearing the brunt of the cuts.

This was – for me, at any rate – just more evidence of the extent to which the Colorado River Compact is a failed document. It was Caliphobia that had brought the seven states together in 1922 – California unenthusiastically – to create the Compact. All seven states had variations on the doctrine of prior appropriation as their foundational water law, and knew that the logic of the law meant they had to honor each other’s senior appropriations. But California was growing so fast, with claims on so much Colorado River water, that the other six states were concerned that there might not be enough water left for their own slower development.

Their goal in coming together was to create a division of the river among the seven states that would override appropriation law at the interstate level, eliminating a seven-state appropriation horserace in which California was already lapping the field. California participated in the compact negotiations because Congress said there would be no money to build the big flood control and storage structures California desperately wanted until the seven states were in agreement on how the river’s water would be apportioned.

They were, however, unable to do the seven-state division they needed. They each came from their own state with estimates of their future needs that, in total, added up to half-again more water than even the 18 maf pluvial river carried in that first quarter of the 20th century. They were operating on dreams, not data, and after a couple days of critiquing each other’s numbers and defending their own, that gave up on the seven-state division.

The best they were able to do, in their November ten-day eleventh-hour do-or-die charrette was the two-basin division that gave the four states above the canyons some protection against California growth, but left the other two states below the canyons in the cage, as it were, with the thousand-pound gorilla, California. The Compact goal of ‘promoting interstate comity’ failed when Arizona refused to even ratify the Compact. And as average flows declined from the 1930s on, the Upper Basin’s Compact charge to ‘not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below’ the Lower Basin’s apportionment began to make the Upper Basin states feel more like juniors shorted to fulfill a senior water right than participants in an ‘equitable apportionment.’

Add in the failure to even mention the basin’s substantial system losses, and the Compact and subsequent Law of the River have not done much to ‘remove causes of present and future controversies,’ culminating in the situation we are in now, with California playing the seniority card on the other states, the Upper Basin and Lower Basin having different ideas about what it actually means to ‘not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below’ an average of 7.5 maf/year, and no one really wanting to face the fact that the Compact was written for a river half-again larger than the river we have now – with a modest but steady decline in this river as we continue to warm the world around it. We are going to have to impose, and accept, significant shortages that will have impacts on all of us, on the way we eat nationwide and how much we pay, as well as how we use water everywhere in the region.

What is truly ‘equitable’ when it comes to administering shortages? Or cutting right to the chase – to what extent should the appropriation doctrine dominate the discourse? Is ‘first-come-first-served’ to be the only measure for ‘equitable allocation’?

To put the question another way: could we acknowledge a distinction between water-use issues and all-river issues? Water-use issues can occur between agricultural users, and between agricultural and urban areas, and between urban areas. We have decided culturally to resolve those kinds of issues through the first-come-first-served laws, and whether that is the best way to resolve issues over water use or not, it is the way we do it. (Although it should be noted that, among multi-generation neighbors, with century-old water rights differing by a year or two, seniors seldom place ‘calls’ on their junior neighbors; they work out ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ to share the available water. Appropriation law can be brutal when strictly enforced.)

But all-river issues are matters above and beyond questions of prioritizing water use. Discovering that we are dealing with a river that is only two-thirds the size of the river the Compact was created for is an all-river issue. Trying to figure out how to do long-delayed water justice for 30 First People nations of varying sizes (with two-thirds of them in one state) on a fully appropriated river is an all-river issue. Managing for the unknown but unfolding consequences of a changing, warming climate is an all-river issue.

All-river issues are everyone’s problems, created and perpetrated by everyone, whether consciously or unconsciously; and in a just world everyone would share the pain of resolution in some equitable and proportionate way. With an all-river issue, ‘seniority’ just means the water user has been part of the problem, consciously or unconsciously, for a longer time.

I have some thoughts about how we could deal with some of our all-river issues, which I will no doubt unload on you over the next several posts, but I hope that if you have thoughts on it, you will unload them on me in comments below.

And I also hope some of the people actually at the table(s) are also trying to think beyond the limitations of the Compact and of the foundational law of the river, the prior appropriation doctrine that the Compact wanted to address but couldn’t. Like Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s main negotiator, said, ‘We must plan for the river we have, not the river we dream of.’

Just an offhand comment from a Midwesterner who’s 1,500 miles from the lower Colorado, and nearly 1,000 miles from the headwaters. As a long-time enthusiast and admirer of the western landscape, I’ve never liked the “prior appropriation” doctrine. “First come, first served” only makes sense if everyone who’s going to be affected knows and understands what’s at stake, and knows and understands the rules of “the game” from the beginning. That seems manifestly to NOT have been the case as the western states were settled, a legal and economic system imposed, etc. More to the point, if “first come, first served” is going to be the operating principle, there are 30 groups of native inhabitants whose claims to water – ethically and philosophically, if not always according to the rules of a society alien to their own (i.e., legally) – precede the claims of most people living now. If anyone is going to profit from the natural resource that is the Colorado River, it ought to be the natives who were here already when John Wesley Powell’s explorations took place.

Powell would have done it differently, title to the water tied to the land it watered – and as the first explorer to think of the First People as something other than a species of mammal in the way of Manifest Destiny, he might have done differently with them too.

Thanks (again), George. Sibleys Rivers adds much-needed clarity to a thorny, mind-numbing issue. I forward it to my old time river runner friends.

Onward,

Vince

-AI photo made me laugh. And I thought the canyon was crowded.

George – why has California, with its direct access to the ocean, not been desalinating seawater in a big way for use in e.g. agriculture? Instead of relying on its senior water rights and pumping out of the ground?

Tino

San Diego has built a big desalinating plant on the ocean – its Carlsbad facility – and has it in successful operation. Its water is very expensive though, and between that and some special arrangements the city has made for bringing water from the Imperial and Coachella irrigation systems, the people of San Diego are feeling pretty stressed about their water bills. Nonetheless, Los Angeles is also exploring options for desalination. Los Angeles is also working hard on stormwater capture and recycling/reuse of domestic water. Out of this winter’s big storm that dropped nine inches of rain on the city, their growing mosaic of green spaces with porous soils soaked up some 8 billion gallons of water.

Shades of Rollie Fischer my friend. He knew this was coming, which is why he hired Eric. But it is like beating your head on a wall, it actually doesn’t ‘hurt so good’ and seemingly no one listens. There is simply too much money involved and enormous amounts of wishful thinking.

It’s snowing here today. Maybe that will help.

Every little bit!