Have you heard of the wonderful one-hoss shay,

That was built in such a logical way

It ran a hundred years to a day …

– Oliver Wendell Holmes

We’ve been exploring the Colorado River Compact here – which, like Oliver Wendell Holmes’ ‘wonderful one-hoss shay’ has now lived almost ‘one hundred years to the day’ – the commissioners signed off on it November 24, 1922. The century mark is a good place to pause and pull back for a larger perspective on something like a multi-state agreement and see what it has and hasn’t actually accomplished – but without losing sight of the romantic vision of conquest that drove the Compact’s formation, back in the early decades of the Anthropocene Epoch when reorganizing the prehuman world was still fun.

In the last post here, we looked at the ‘major purposes’ cited in the first article of the Compact: the first listed purpose, ‘to provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters

of the Colorado River System’ in order ‘to remove causes of present and future controversies’ (fourth purpose); and the final listed purpose, ‘to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial

development of the Colorado River Basin.’

That fifth purpose, to facilitate the expeditious development of the Basin, was the main reason the seven state representatives had convened with a federal representative: they all wanted to get about the development of the river’s waters, the desire to take on Frederick Dellenbaugh’s ‘veritable dragon’ supported by rational reasons such as flood control and storage. In order to achieve that expeditious development, however, it was necessary to achieve the Compact’s first stated purpose: an equitable division and apportionment of the development and the water required – or cutting to the chase for most of the seven states: making sure that fast-growing Southern California did not get most of the water for its racehorse development.

After failed efforts to make specific seven-state divisions of the use of the River’s water, the expedient solution they settled on was to divide the river in two, around the mostly uninhabited canyon region: an Upper Basin including the four states above the canyons (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming), and a Lower Basin of the states below the canyons (Arizona, California and Nevada). It was their clear intent that each basin would get half of the river’s water for consumptive use, with the states in each basin working out an equitable division among themselves of their half, in their own good time.

It may have worked out better, had they stopped there – a 50-50 division of whatever water the river produced, with each basin responsible for half of whatever water might eventually by allotted to Mexico where the river ended. But California insisted on a specific quantification of the two shares because they were already using a substantial amount and didn’t want to over-appropriate. After much discussion and good and bad advice, the commissioners settled on 15 million acre-feet (maf) as a reasonable average flow, between the Bureau of Reclamation’s optimistic 16.5 maf and the less optimistic 13 maf of USGS scientists studying the river.

The commissioners have been chided – castigated – for settling on the 15 maf quantity, which was shown to be overly optimistic within a couple of decades. But they could have countered the criticism by asking why, if their numbers were so bad, had the states not reassembled to correct them?

Frequently in their meetings, there was either frustration or resignation at how little they knew about the river and its flow history. Chairman Hoover summarized that oft-expressed concern in their 21st meeting: ‘[W]e make now, for lack of a better word, a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime, we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river.’ (Italics added) In other words – we can work out the details down the road when we know more; meanwhile, let’s build dams and canals. They built into the Compact, in Articles III, VI, and IX, procedures for those ‘possessed of a far greater fund of information’ to reconsider the Compact to better fit the emerging reality of the River and its flows.

I should note that the commissioners, Anthropocene romantics, actually believed that future generations would reassemble to address the distribution of surplus flows. They anticipated a larger river in the future – if not provided by nature, then by the engineers who would bring in more water from larger rivers that had a surplus. This is the ‘romance of the Colorado River’ – the romance of the Anthropocene.

California’s commissioner McClure accepted the lower 7.5 maf/year figure because it moved along the process leading to stymying the veritable dragon with a big dam for storage of the river’s annual flood. But Arizona’s commissioner, W.S. Norviel, was not happy with any aspect of the two-basin division since it left Arizona competing with California for a diminished quantity of water, a mere half of the river, for which the bigger state already had plans in the process. He was essentially – on orders from economic forces in the state he represented – in a defensive posture, protecting Arizona’s right and capacity to become another California with no interference from the Upper Basin states. Most of the commissioners were patient with Norviel, but frustration was occasionally vented, as when the New Mexico commissioner observed that ‘we are absolutely and utterly up in the air because none of us knows what it is Mr. Norviel really wants.’

What it came down to – what satisfied Mr. Norviel enough to reluctantly sign the Compact – was the concession by the Upper States that Arizona’s tributaries to the Colorado River mainstem would not be counted as part of the Lower Basin’s 7.5 maf/year. This is obscurely codified in the Compact as the mysterious statement in Article 3(b): ‘In addition to the [7.5 maf] apportionment, the Lower Basin is hereby given the right to increase its beneficial

consumptive use of such waters by one million acre-feet per annum’ (with no additional responsibility for that accruing to the Upper Basin).

No rationale for this ‘gift’ is to be found in the minutes of the meetings, but it would be naive to think that everything of importance happened in the formal transcribed meetings. Bishop’s Lodge had a comped bar and restaurant, and there were undoubtedly informal meetings, over breakfast and lunch and well into the evenings, and in hotel-room Basin caucuses, as well as phone exchanges with interested parties back home.

The Compact that the seven commissioners signed in late November 1922 might have raised as many questions as it answered for the states and the nation. That unexplained million acre-feet is one such instance. But the big one was, and continues to be – what did the commissioners mean when they said, in Article III(d): ‘The States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate

of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.”

Does this mean – well, what it seems to say: that the users in the Upper Basin states should do nothing themselves, in the way of consumptive uses, to deplete the flow at Lees Ferry below the 7.5 maf/year average? Or does it mean that the Upper Basin has a ‘delivery obligation’ to the Lower Basin regardless of what happened naturally (drought) as well as culturally (over-use) in the Upper Basin?

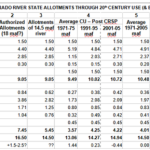

That particular question has remained unanswered because there has been no need to raise the question – yet. The Upper Basin is now consuming only around 4 maf/per year, with nearly all of its good agricultural land watered. Colorado commissioner Carpenter had opined early in the meetings that even at full development the Upper Basin states would still be passing more than half the river to the Lower Basin; that seems prescient in retrospect.

Upper Basin depletions today also include two-thirds of a million ace-feet in out-of-basin diversions to the South Platte, Arkansas, and Rio Grande rivers and the Salt Lake region. Such diversions could conceivably be a black hole into which another million or two acre-feet could be poured, but users in the natural Upper Basin are organized enough now to put very expensive conditions on future out-of-basin diversions – as Denver Water and Northern Water have learned, on ‘firming projects’ for two relatively small diversions into the South Platte for which they already had conditional rights. The Upper Basin states assumed the worst – an unconditional delivery obligation – and have been almost obsessively diligent about keeping the ten-year running average well above 75 maf. Even today, through two decades of aridification, the ten-year average remains in the 85-90 maf range, although the long-term trend in the running average is downward, bringing closer the day when that big question must be answered…

The mysterious or obfuscatory passages of the Compact to one side, however – a larger question, for me at least, is whether the division of the Colorado River into two basins was a good idea for the long term.

As Utah’s commissioner Caldwell observed in the next to last meeting, ‘I think for a practical matter we are almost making two rivers out of one in the Colorado River, to meet a practical situation.’ The ‘practical situation’ was the need for an interstate agreement on the consumptive use of the River’s water ‘to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial

development of the Colorado River Basin,’ and the two-basin concept achieved that.

But the effect over the century has been ‘almost making two rivers out of one,’ rather than developing one river with two basins. The Upper Colorado River is a ‘natural’ river, accumulating its flows from many mountain tributaries that almost all start with snowmelt above 8,000 feet in elevation and gradually conjoin to funnel into the canyon region. The Lower Colorado River is practically a reverse of that, with a single source emerging from the canyon reservoirs and gradually being diverted into canals and smaller ditches and pipes until it has been literally all spread out in southwestern desert destinations.

The clear intent of the Compact commissioners was that these two rivers would be created equal (‘to remove causes of present and future controversies’), but they failed to deliver that in the language of the Compact. Despite some wiggle room provided by the ten-year running average, the Upper Basin was clearly going to bear most of the burden of nature’s extremes like drought, while the Lower Basin was assured under the Compact of a relatively consistent flow of water from storage regardless of what happened in the Upper Basin.

The separation into ‘two rivers’ was enhanced with the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and Powell Reservoir just above Lees Ferry the basin division point; there was no further need for the Lower River to be concerned at all with the occasional dry spell in the Upper River; their portion plus the Upper River’s share of Mexico’s portion (8.23 maf/year) was always there – plus the unused Upper River ‘surplus’ which the Bureau kept sending them, enabling all manner of bad habits in the Lower River.

The problem with ‘making two rivers from’ the Colorado River is a failure to take into account the basic nature of a ‘desert river.’ Around 85 percent of the water for the entire Colorado River Basin originates in the Upper River above 8,000 feet elevation. And around 65 percent of that water is consumed by the Lower River (whose water ‘originates’ in the bubbling ‘spring’ of spent water from Glen Canyon Dam’s power turbines). Yet the Lower River is charged with no responsibility for maintaining and improving the source of its water. The back-and-forth fussing and complaining today between the two basins is evidence of a two-river split, in which the problems of flow lie mostly in the Upper River, and means for addressing those problems ($$$) are mostly untapped in the Lower River’s users.

The Compact commissioners undoubtedly did the best they could with the knowledge they had – and the romantic vision they tried to carry forward in more rational terms: they were primarily out to get about the task of unleashing the Industrial Revolution on Frederick Dellenbaugh’s ‘veritable dragon.’ But their own words in the transcriptions, as well as the ‘reform’ clauses in the Compact itself, indicate that they intended for the Compact to be a ‘living document,’ changing as we learned more about the river.

Why have the Compact’s critics not delved into the document’s weak points and unforeseeable challenges? Some elements of the so-called ‘Law of the River’ – which we’ll explore soon – have attempted to either chip away at the challenges, or to circumvent them. But the tasks of correcting the arithmetic and addressing the two-river questions can no longer be kicked down the road – like Holmes’ one-hoss shay, the Compact could fall apart at a hundred years to a day.

Hi George,

I always look forward to your next episode. In this one, your language in the paragraph beginning, “The effect over the century is almost the making of two rivers…” is particularly beautiful, I thought.

Best, Paula

So enjoy learning this history. You do a great job of making it understandable even to someone with no background on the subject. Terrie

Thanks, George. I wish I thought we would consider the greater good for the environment as we “figure out” how to deal with this problem.

Great work, George. On a recent road trip (first one since Covid) through the four corners area, we noticed that the restaurants were asking if we wanted any water with our food-a new development.

BTW, first snows are showing up on Longs Peak.

Well written article. I commend you for writing about what really happened vs the empty talking points most journalists use writing about the Colorado.

I’ve accumulated all the documents needed to fully understand what happened to the Colorado on my research server:

http://www.varuna.io/LOTR/chron.html

I have pie charts on Twitter showing where the real over allocation of the Colorado occurred:

https://twitter.com/edmillard/status/1578107884440649728?s=20&t=3NXfs7UnwfFr1VURjPNHwQ

The 1928 BCPA, wrongly interpreted by the Supreme Court as a law dividing the river and removing the Gila from the Compact, was just a suggestion by Congress for a Lower Basin Compact that AZ and CA never signed, read Sec 4:

https://www.varuna.io/LOTR/1928/bcpact.pdf

Justice Douglas dissenting opinion skewered how bad the AZ v CA decision was:

https://www.varuna.io/LOTR/1963/Arizona_v_Californiat_Dougles_Dissent_1963.pdf

The Mexico Treaty traded 750 kaf on the Colorado to Mexico so Texas could get more water from the Rio Grande. Texas Sen Tom Connolly chaired Senate Foreign Relations and had the power to get State Dept to do the deal. Interior Sec Ickes wrote to FDR complaining about it before ratification here:

https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1944v07/d1291

This Law Review Paper written by AZ’s Shiffer & Guenther explains how they used litigation threats in 2005 to expand releases from Lake Powell to 9 maf in the Interim Guidelines:

https://arizonalawreview.org/schiffer-guenther/

Thank you, Ed, for this truly substantial expansion on the Law of the River. You are a light-year or two ahead of my efforts to muddle forward in analysis of the unfolding debacle on the Colorado.