In the last two posts here (one of which you got twice, my apology), I’ve been trying to ‘revision’ the Colorado River as the classic desert river that it is. All rivers are composed of runoff – water from precipitation that did not soak into the ground, collecting in streams that ‘run off’ to the next lower watershed. Humid-region rivers receive new water from unused precipitation all the way along their course to the sea, but a river in the arid lands obtains nearly all of its water as runoff from a highland area high enough to force water vapor to condense into precipitation. The resulting runoff from that precipitation then flows down into the arid lands where it receives very little additional moisture and thus starts to diminish through natural processes on its way to the sea – evaporation under the desert sun, riparian vegetation use, absorption into low desert water tables. When the deserts are large enough, and the rivers’ highland water supplies erratic enough, some desert rivers disappear entirely, seasonally if not year round, before they get to the ocean.

As a desert river, the Colorado River divides naturally into a water-producing region in mountains mostly above ~8,000 feet elevation (only about 15 percent of the basin area, mostly in the Southern Rockies), and a much larger water-consuming region of arid lands, both orographic ‘rain-shadow’ deserts and hot subtropical deserts. Because the majority of its surface water comes from snowmelt, the pre-20th-century Colorado River regularly sent an early summer flood of water down into the Gulf of California, but later in the water year, snowpack gone, it probably did not always make it all the way through its jungly delta to the sea. Today, with 35-40 million water users in the Colorado River’s water-consuming region as well as those natural processes, the highly controlled river only makes it (almost) to the ocean in an occasional planned release.

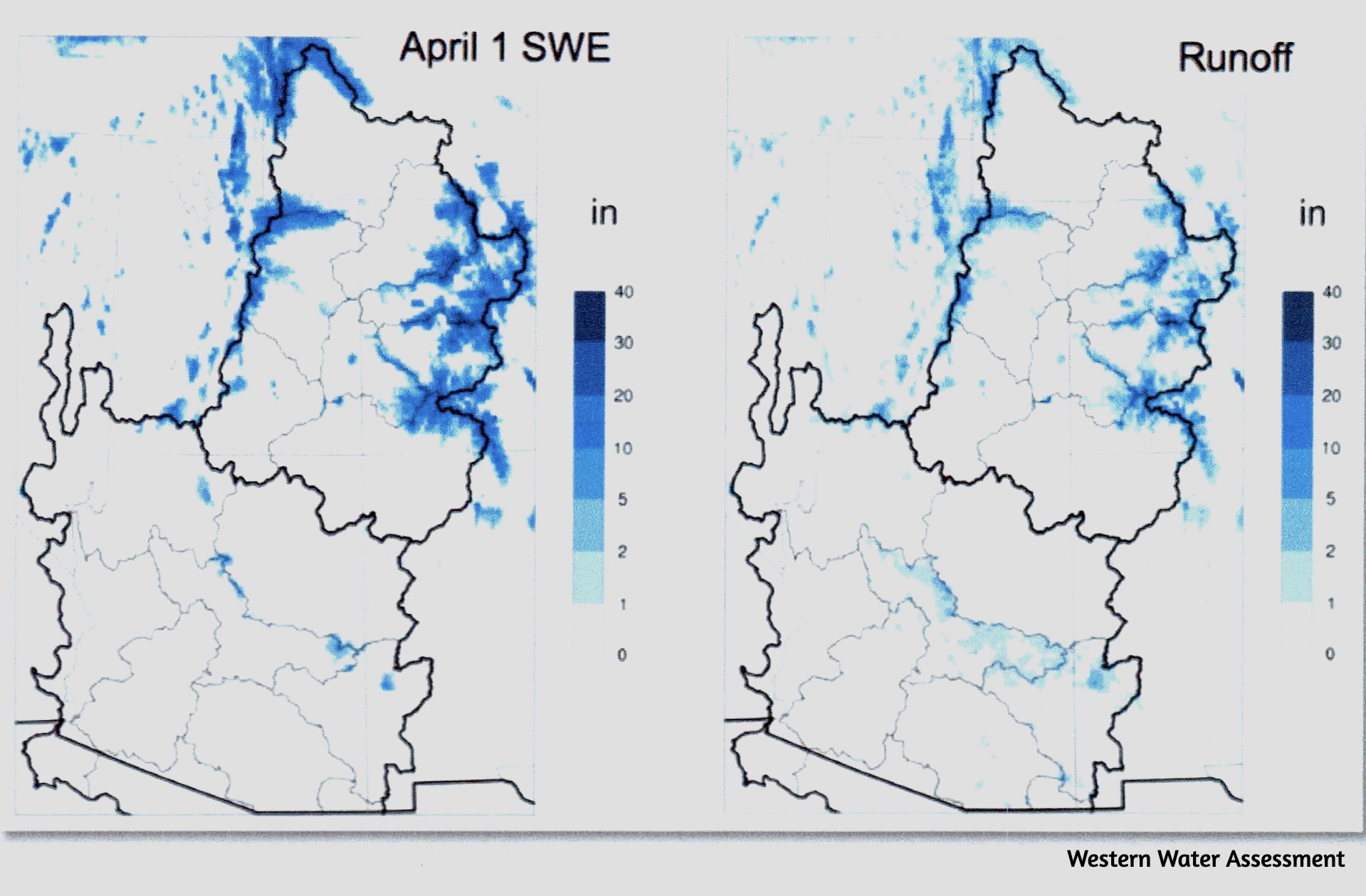

In the last post we began exploring the river’s Headwaters – its water-producing region. To refresh your memory, here’s is the set of maps that, in effect, show the river’s water producing region – the blue areas on the map on the left, which show the average quantities of water (snow water equivalent) held in the peak snowpack, usually late March or early April:

It’s important to note that the water-producing and water-consuming regions of the Colorado River region are not congruent with the Colorado River Compact’s Upper and Lower Basins (above and below the line dividing the area outlined in black). The water-consuming region consists of nearly all of the Lower Basin and most of the Upper Basin – and includes all the trans-basin consumptions via long canals and tunnels).

The river’s actual water-producing region (blue areas inside the black line) is barely a fourth of the Upper Basin and some Lower Basin uplands that produce water for the Gila, Virgin and Little Colorado Rivers. That region is our focus today.

I will begin by suggesting that the 35-40 million of us in the water-consuming region of the Colorado River Basin (plus extensions) should have an investment of at least interest and concern, if not (yet) a fiscal investment, in our river’s water-producing region.

Whoa! What’s that? In addition to doing everything we can to conserve and extend the water we use in our deserts – we arid-land river users have to be involved – maybe eventually financially – with the river’s water-producing Headwaters as well? Why shouldn’t the people that live there take care of that?

One obvious reason is the fact that comparatively very few people live in the Headwaters above 8,000 feet. Nearly all of it is public land, National Forests managed for the ‘multiple uses’ of all the people. But the larger reason for water users in the consumption region to be investing at least attention and political interest in the Headwaters is the fact that we – the 40 million of us consumptive users – are the people with the greatest direct interest in what happens in the mountains. We depend on those Headwaters for 90 percent of our water supply, and our concern ought to be apparent: we want as much water as possible making its way out of water-producing region into the region of consumption, especially as our river’s flow diminishes by the decade.

Because the border between the water-producing region and the water-consuming region is a natural rather than political boundary, it is not really a line at all (like the 8,000-foot contour), but more of a blurry edge zone, an ecotone with varying levels of both water production and consumption in it. In Gunnison where I live, for example, at 7,700 feet elevation, we receive on average just a little over 10 inches of precipitation annually – the upper edge of an arid region that continues down through the Colorado River Basin to the river’s end in the subtropical deserts. But 30 miles up the valley from Gunnison, the town of Crested Butte at 9,000 feet gets around 24 inches a year on average, a water-consuming community up in the water-producing region – and all of the valley floodplains between the two towns that are not yet subdivisions are in irrigated hay fields. This is the ecotone, the edge zone in which the net balance between water production and water consumption gradually shifts, over a mere 30 miles, from mostly production to mostly consumption, as precipitation diminishes to desert levels.

Mining and resort towns above 8,000 feet are, however, pretty minor consumers of precipitation-produced water, compared to consumption by natural forces at work in the area. In the last post we explored some of those natural forces in addressing a mystery posed by the Western Water Assessment’s report on the ‘State of Colorado River Science’: ~170 million acre-feet of precipitation fall on the Colorado River Basin every year on average, but only ~10 percent of that becomes the river’s water supply. What happens to the other 90 percent?

The perpetrators of this loss turn out to be the sun that originally ‘distills’ the freshwater from the salty ocean and the prevailing winds that carry it across a thousand miles of mountain and desert to condense it into a snowpack in the high Rockies. The sun and wind give, and the sun and wind take away – starting immediately after the giving.

The precipitation forced from water vapor in the air by our mountains is barely on the ground before the sun and wind are trying to return it again to vapor. Throughout the main water accumulation period, the winter, sublimation – the conversion of ‘solid water’ directly to water vapor by sun and wind – is eating away at the exposed snowpack every sunny or windy day, even at temperatures well below freezing.

Then once the mountains warm up enough for the snow to melt, the sun and wind evaporate what they can of the water that runs off on the surface, especially where it is pooled up or spread out on the streams’ floodplains. The snowmelt water that sinks into the ground goes into the root zone of all the vegetation on the land – grasses, shrubs, brush and trees – where it is sucked up by the thirsty plants, with most of that being transpired back into the atmosphere as water vapor to cool and humidify the working environment of the plants.

Sublimation, evaporation, transpiration – exactly how much water each of these activities of sun and wind convert back to water vapor is difficult to measure, but the end result is that less than a quarter of the water that falls on the mountains stays in the liquid state as runoff creating the streams that become the river flowing into the desert regions where 35-40 million of us depend on it, and less than five percent of what falls on the water-consuming desert regions augments the river there. The sun and wind give, and take away.

The question arises: are there not some ways in which we might retain or recover some of that lost water? That question may begin to sound like another charge for planet engineering – crystals in the stratosphere to reflect heat away from the planet, et cetera. I am not so ambitious as that.

But we know that the Colorado River has lost as much as 20 percent of its water over the past several decades from a combination of climate warming and drought, and even if the drought ends, we will lose more in the decades to come from the warming of the climate already made inevitable from our ongoing reluctance to do much about it. Scientists estimate that for every Fahrenheit degree of average temperature increase, we will lose 5-7 percent of our surface waters from heat- sublimation, evaporation and transpiration. So is there anything we can do – affordably, and undestructively – down here where the water is, to mitigate that loss, if only partially?

Obviously, the sun and wind rule unchallenged in the highest Headwaters, the treeless alpine tundra. But as one moves down into the treeline – another ecotone with the subalpine spruce-fir forest gradually becoming the dominant ecology over the miniature plants and windbeaten krumholz trees of the tundra. The forest shades the snow that makes it down to the snowpack from the sun, and shelters it from the wind. But the forest also catches a lot of snow on its branches, and that snow is prey to the sublimating sun and wind.

The shading trees also slow how fast the ground snowpack melts; in the deep forest, patches of dirty snow can last into the early fall. A slower melt means a higher ratio of water sinking into the ground over water running off to the 35-40 million of us waiting for it downriver. But the trees of the forest exact a high price for their protective efforts; the water sinking in is sipped up by the roots of all the forest vegetation, and the trees are heavy drinkers, transpiring most of what they drink.

Nearly all of the forests that run a wide belt through the Colorado River Headwaters region – the subalpine spruce-fir forests and the montane pine forests – are, as mentioned earlier, public lands designated National Forests, set aside to protect them.from the Early Anthropocene Age of Plunder. A huge number of them were designated by President Theodore Roosevelt, considered the Father of American Conservation, with forester Gifford Pinchot riding shotgun. Pinchot probably had a hand in crafting the 1897 Organic Act that created the National Forest concept out of scattered federal ‘Forest Reserves’ set aside under earlier legislation, but with no management or legally impowered managers explicit.

The Organic Act was fairly explicit in defining the purpose for creating National Forests:

No public forest reservation shall be established, except to improve and protect the forest within the reservation, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States….

Recognizing that just setting the land aside with no process for ‘improving and protecting the forest’ was, in the still pretty wild West, equivalent to hanging a sign on the reserve saying ‘Get it while you can, boys, because someday you might be banned,’ the Organic Act also provided for ‘such service as will insure the objects of such reservations’ – which ‘service’ became, under Roosevelt and Pinchot, the U.S. Forest Service.

Note that there are two fairly specific charges in the quotation from the Organic Act: ‘securing favorable conditions of water flows,’ and ‘furnishing a continuous supply of timber.’ Given the circumstances of a nation continually growing and building, with the American dream being a home of one’s own, it goes without saying which of those two tasks the evolving Forest Service has been mandated to prioritize. For much of their history, the Forest Service has been expected to fund themselves with a surplus to the U.S. Treasury through timber sales – always harvesting of course in ways that ‘improve and protect the forest’ (possible, but increasingly improbable when demand grows extreme and supply trudges along at nature’s unhurriable rate).

The charge to secure favorable conditions of water flows, however, has been given much less attention. Pinchot said that ‘the relationship between the forests and the rivers is like the relationship between fathers and sons: no forests, no rivers.’ That is clearly not the case; the forests are not the creators of rivers, they are instead just the first major user of the rivers’ waters; they protect the snowpack and slow the melt for their own needs. Pinchot was right in perceiving a relationship between forests and rivers, but had it backward: ‘No water, no forests’ is more accurate.

One might think, then, that in the Headwaters of the most stressed and overused river in the West, if not the world, the managers of the Headwaters forests might be expending serious effort to make sure that they are securing the most favorable flows possible from their forests.

What I am having trouble discerning is whether the Forest Service is paying any attention at all to any responsibility for a water supply that 35-40 million people are depending on. In my ‘home forest,’ for example, the Gunnison National Forest – now bundled together for management efficiency with two other National Forests as the ‘Grand Mesa Uncompahgre Gunnison National Forests (GMUG): the first draft of a GMUG Forest Management Plan being drafted over the past 2-3 years did not even mention the Colorado River Basin by name as a larger system they are part of, and hugely important to. Response letters from ecofreaks like me (I assume others also wrote them about this) got a paragraph about that larger picture into the final draft – but nowhere in the plan itself did I find explicit discussion of the larger mission that implied and of specific management strategies for making sure that the plan was fulfilling that organic charge of securing favorable – one might say ‘optimal’ – conditions of water flows.

Well – that launches into an exploration of National Forest management policies and activities that I am still trying to muddle through, but that can wait till next month. I’ve gone on long enough here for now, in this effort to peer over the edge of the box we’re all supposed to be trying to think outside of – the ‘Compact Box’ that all the water buffalo are still stalemated over, as we all try to envision river management after the expiration of the Interim Guidelines from 2007. Stay tuned.

Indeed… stay tuned. And local (as well as national) politics will surely play a substantial role in whatever result emerges. There may be political figures in the Headwaters region who might be credible environmentalists – “pro-river,” if you will – but from my significant distance, I see little evidence on the current national political scene of those kinds of politicians. Rare, indeed, is the businessman/woman (and likewise, the politician, of whatever gender) willing to take the risk, and deal with the criticism, that likely comes automatically with a long view of the interplay between environment and economy. Stockholders are generally interested in next quarter’s dividend figures, not those of a generation in the unknowable future.

Too true, Ray.

Quite telling that no mention was made of the Colorado River Basin and no plan for protecting its flows. A serious omission given the enabling legislation for the USFS.

The Forest Service has just been driven into the timber corner by national priorities and the silvicultural inclination until the graduates of the past half century who have learned about ecology, but they’re mostly the ones who haven’t ascended to the top ranks….

Thank you, George. So informative. I knew that picture was the East River meanders without the caption! I have to give a presentation about our this year’s club topic, “West of the Mississippi”. So I have to pick a book or two. We actually read from books. One is Encounters… by McPhee. I am also thinking about some excerpts from Shoumatoff’s Legends of the American Desert. I still think McPhee is relevant to the two topics that are of tantamount relevance today: mining and water. Would you have any other suggestions? Mary Reed Earl

I don’t know Shoumatoff, Mary! Something new to look for; thank you. Mining is less of a presence in the Southwest today; the big unraveling discourse over water is between agriculture and recreation/environment. That could, of course, change if uranium becomes a viable mineral again in gearing up for more nuclear energy…. A three- or four-way contention then. The First Peoples becoming part of the discourse over water is another significant change today.

George: Another excellent, albeit discouraging, piece by the Gunnison Wordsmith.

Ecofreak or not, you are embracing important issues that impact even those of us who understand very little of the balance between production and consumption. Anxious to hear more of the story.

Thanks, Carl. I’m trying to get through it a fumbling step at a time. But I think that’s how we travel when there’s no path laid out….

I am increasingly coming to the conclusion that our 100 to 200 plus year old agencies regarding natural resources are too moribund and rooted in past glory to even comprehend the needs of a growing nation in a time of extreme climate and political change…much like large parts of the Constitution that have so been badly distorted by political jurists rather than any reasoned thought. So I guess I feel hopeless. Glad to have one voice still trying to be heard. Hells bells, I cannot even get my recycling picked though I am concluding nothing gets recycled anyway no matter how much extra I pay.

Courage, old friend – I don’t think we can keep going without a little naivete…. Like believing that the species will come to accept that thinking things through intelligently will be the only way we’ll survive….

Morning George. I’m going to be in Gunnison late next week and hope I can see you. Morning coffee on Friday, 10/18?

Thought provoking as usual, George. Thanx. But ‘thought provoking” usually leads me to “question asking” as it did twice with this installment:

1 – IF you were ever seriously asked by pro-river policy makers – either in or out of the USFS – to list what your believe ought to be that agency’s top 5 changes in its historical interpretation of its mission that “could improve specific management strategies for making sure that the plan was fulfilling that organic charge of securing favorable – one might say ‘optimal’ – conditions of water flows”, what would those 5 changes be? And,

2 – Why not not just find that “very large faucet,” that one self-designated water expert recently detailed so eloquently:

“You have millions of gallons of water pouring down from the north, with the snow caps and Canada, and all pouring down. And they have, essentially, a very large faucet, and you turn the faucet, and it takes one day to turn, and it’s massive … and you turn that, and all of that water goes aimlessly into the Pacific. And if you turned it back, all of that water would come right down here and right into Los Angeles.”