“Now we have to come to terms with the fact that there are limits.

That’s not the American way to recognize limits.”– Jack Schmidt, Director

Center for Colorado River Studies

University of Utah

For the past several posts, we’ve been exploring the Colorado River Compact, commemorating its centennial this year. Nearly everything I have read about the Colorado River Compact in this centennial year – and it’s getting to be voluminous – speaks of it as the ‘foundation’ of ‘The Law of the River,’ an accumulation of legal and political documents accompanying the development of the Colorado River since the 1922 Compact.

I have a problem with calling the Compact the ‘foundation’ of the Law of the River – as though before the Compact was adopted, the River was lawless. That is not true. The real foundation of the Law of the River is the appropriations doctrine that all seven states (or territories) had embraced in the 19th century – an evolving body of ‘common law’ that is the foundational law of all modern water development in the arid American West.

There is much to appreciate in the appropriations doctrine, which we explored a month or so ago. It democratically only allows the appropriation of the amount of water an appropriator(s) can beneficially put to use, to prevent big money speculation. It protects existing ‘senior’ downstream users from being dried up by new upstream ‘junior’ users. Among other virtues, it has shown flexibility in opening up to incorporate new uses like recreation and the environment.

But the appropriations doctrine also evolved as a powerful engine for growth. Its basic ‘first in time, first in right’ promise of perpetual secure use rewards those who get there first, regardless of what they do so long as it can be construed as economically beneficial, which we now know covers a multitude of sins against both nature and human nature. And ‘judicial expansions’ to the basic law really increased its potential for nurturing growth. The abstract ‘right to use water’ for some specific decreed purpose came to be a property that could be bought and sold like land itself – along with its seniority. The water whose use was purchased could be moved anywhere from its natural watershed with a simple change of purpose, enabling cities with limiting natural water supplies but concentrated economic power to accumulate water from great distances – including water they were not yet ready to use, exempting their ‘prudence’ from the anti-speculation law.

The appropriations doctrine is thus like the reactor in a nuclear power plant, an explosively powerful energy. What makes a nuclear power plant functional is a whole set of systems designed to contain, control, slow down, cool down and spread that explosive energy – turn it from a potentially destructive force to beneficial use.

The Compact commission came together 100 years ago to construct exactly that kind of control mechanism around the appropriation doctrine. Appropriation law based on seniority had emerged as a way of working out local problems; but as the land filled up, the logic of the law seemed to decree that prior appropriations would have to be honored across shared watershed boundaries – and then across state boundaries, in a stream shared among states. That was in fact being tested in the early 1920s in the U.S. Supreme Court, arbiter of interstate conflicts: the state of Wyoming sued the state of Colorado, on behalf of some Laramie River irrigators with decreed water in Wyoming that Colorado diverters upstream were threatening to cut off.

Colorado water attorney Delph Carpenter had argued, in Wyoming v. Colorado, that the users in every state had the right to develop as much water as they could under their own law, and there would still be plenty to flow to downstream states. But Carpenter assumed he would lose that one, that the court would decree that the states would have to honor each other’s appropriations (which it did in June 1922), and he worried that the growth dynamic of the appropriation doctrine would then launch a ‘seven-state horserace’ with each state trying to appropriate as much water as possible as quickly as possible – with fastest-growing California half a lap ahead at the start, and the courts would be clogged with Wyoming v. Colorado situations. His concern, expressed to others in the region with similar concerns, led to the creation of the Compact Commission in 1922.

The question now, at the century mark, is whether the Compact actually succeeded in an equitable division among the states that prevented the ‘seven-state horserace’ – or whether the division into two basins just turned the seven-state race for appropriations into four-state and three-state races, since none of the states ever really damped down the drive for growth. (Arizona commissioner W.S. Norviel expressed that concern about the two-basin division in Compact meetings.)

The Compact did set a limit of 7.5 million acre feet (maf) for each Basin to use to depletion – but the Compact does not really present that as a limit; it is to be considered a major component of something to be worked out further as distribution from an uncommitted ‘surplus’ becomes possible. The short answer to the question would be that the Compact was very gentle, perhaps too gentle, in fitting the appropriations growth machine with brakes and steering. But the Compact is only the second (if you accept my analysis) element in the Law of the River. How does the further iteration of the Law of the River help or not help the rationalizing of the appropriation doctrine? Three elements came out in the decade following the Compact….

1928 – Boulder Canyon Project Act

1929 – California Limitation Act

1931 – California Seven-Party Agreement

The element following the Compact in the evolving Law of the River, as day follows night, was the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1928 – the Congressional enabling legislation for the big bold strokes to control the Colorado River, teach it to stand in and push rather than cut and run. This was the first big step in the Compact’s main goal: ‘to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial

development of the Colorado River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property from floods.’

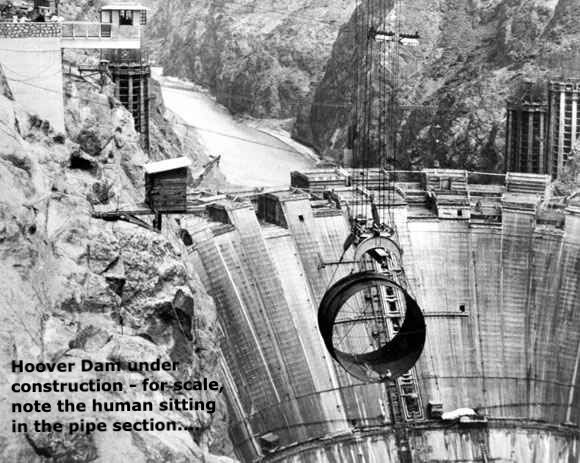

The keystone of the Act was the construction of the great dam, Hoover Dam, that would stop the downriver flooding and store the river’s water – two years’ worth of the river’s flow! No one had ever built such a large dam, and this was being built in a remote desert. A railroad spur had to be run; a steel-rolling mill built capable of creating and moving steel pipe segments 30 feet in diameter; a cement plant and rock-crushing facilities capable of producing and moving four million cubic yards of concrete over three years. The river had to be moved out of the way before work could start on the dam, run through a 50-foot diameter bypass tunnel – a task that took most of the first year.

But the great dam was only one part of the Boulder Canyon Project. It also included the Imperial Weir Dam and Desilting Works 200 miles downriver, diverting a huge portion of the river’s water into a new ‘All-American Canal’ to move the water over to the Imperial and Coachella Valleys without having to go through Mexican territory to get there. And getting the dam under construction inspired the new Metropolitan Water District, serving the many suburbs in search of a city in the Los Angeles-San Diego area, to begin construction on a 250-mile aqueduct from the Colorado River below the big dam. In addition, every gallon of water that went through the dam passed through a hydropower turbine. And all of that was completed by the beginning of World War II – water, food and power for what was America’s fastest-growing urbanizing and industrializing region.

Possibly more important than the natural challenges overcome, however, was the coming-together of the private and public sectors, which set a standard for the 20th century. Hoover Dam was built by a consortium of modest-sized contractors (operating under the name ‘Six Companies’) who had done nothing on that scale – yet it was completed months ahead of schedule and under budget. Spearheading the project was Henry J. Kaiser, who went on to other mega-dam projects, and then to ship-building during the second World War. The private sector knew how to do things it could not afford to do with private-sector funding; the public sector, however, could amass substantial long-term funding to do things beyond the relatively quick return on investment the private sector required. This project was put together under the often maligned administration of President Herbert Hoover – and set the model for much of Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal.’ So much so that Roosevelt could not tolerate naming the dam for ‘Hoover,’ and dedicated it in 1936 as ‘Boulder Dam.’

On a spectrum bounded by ‘Controlling the River’ at one end, and ‘Controlling the Growth Energy of the Appropriation Doctrine,’ the Boulder Canyon Project clearly swung far toward the former. But Congress, in the Boulder Canyon Project Act, also tried to do for the Lower Basin what the Compact Commission could not bring itself to do, and that was to set limits for the individual states. Of the Lower Basin’s 7.5 million acre-feet of water, Congress decreed that California would get 4.4 maf plus half of any designated surplus; Arizona would get 2.8 maf plus the flow of its tributaries like the Gila River; and Nevada – which did not have much going on at all in its southeastern area before dam construction began – would get 300,000 af.

The extent to which California was feared in the rest of the Colorado Basin for its fast growth and growing political power was also indicated in the Act by a legislative demand that California pass legislation limiting itself to the 4.4 maf designated in the Act. The state complied with that in 1929 – the fourth specific action in the evolving Law of the River.

But two years later, on the eve of construction beginning in the Black Canyon (not Boulder Canyon), California water user groups adopted a ‘Seven-party Agreement’ – the fifth ‘Law of the River’ element – that laid some fairly specific claims on ‘surplus water.’

‘Surplus water’ in Colorado River discussions has had three components: most of it (and the most real part of it) was Upper River Basin water that those states were not ready to use, so it flowed on to the Lower Basin, which saw no reason to not ‘borrow’ it rather than wasting it to the ocean. Another, more ephemeral ‘surplus’ component was a million or two acre-feet of water above and beyond the 15 maf divided in the Compact (plus whatever the Mexican allotment would be): the balance of BOR Director Davis’s estimated 16.8-17.5 maf average for the 20-some years of rough records, which would be allotted at some future time. A third, even more ephemeral component was water that the engineers would be ready to import into the river from some larger river, once the Colorado’s water was fully developed.

Remember: contextually we are still back at the naive beginning of the Anthropocene, when everything was still possible. Today, all three components of ‘surplus water’ in the two Colorado River Basins have disappeared – the naked facts have prevailed over the radiant colors of the early romance of engaging the river.

But in 1931 – even with a drier period emerging – a future of surplus was an article of faith, and the ‘Seven-party Agreement’ among the major California water users not only specifically defined how much of the state’s annual 4.4 maf would go to the agricultural users (3.85 maf) and to the new Metropolitan Water District for the Southern California coastal cities (550 kaf); it also got specific about another 962 kaf of surplus water: 662 kaf for the coastal cities and 300 kaf for agriculture – essentially a 10 percent ‘temporary’ expansion of their 4.4 maf allotment.

This was getting pretty specific about something so ambiguous as the ‘surplus water’ described above. But the Metropolitan Water District took it a step further: they designed and built their Colorado River aqueduct to carry not just their designated 550 kaf per year, but the ‘surplus water’ too. They were, in other words, building an aqueduct designed to carry twice their actual allotment; Southern California would grow on borrowed water.

This is why the other states – especially Arizona – were not eager to be sharing the river with California. And it also suggests that the crafters of the Compact and these subsequent LOTR measures were less interested in containing and harnessing the growth energy of the appropriations doctrine than in just grabbing the mane and running with it.

Here at the other end of the Compact’s century, we have to ask if the real underlying foundation of the Law of the River might not be some – well, law of the river itself. It might be good to articulate what law(s) a desert river abides by before inviting 40 million people to partake of it…

Meanwhile – here is an overview timeline of all the elements of the Law of the River as they unfolded over the past century (with gratitude for most of the list to the late lamented Justice Greg Hobbs). This will make no sense right now, but we will be looking more closely at most of them over the coming posts…

1860s to present – Evolution of Appropriation-based Water Law

1922 – Colorado River Compact

1928 – Boulder Canyon Project Act

1929 – California Limitation Act

1931 – California Seven-Party Agreement

1944 – United States-Republic of Mexico Water Treaty

1948 – Upper Colorado River Basin Compact

1956 – Colorado River Storage Project Act

1963 and 1964 – Arizona v. California decision and decree

1968 – Colorado River Basin Project Act

1970 – Operating Criteria for Colorado System Reservoirs

1974 – Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Act

1992 – Grand Canyon Protection Act

2001 – Interim Surplus Guidelines

2003 – Colorado River Water Delivery Agreement

2003 – California Quantification Settlement Agreement

2007 – Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake

Powell and Lake Mead

2019 – Drought Contingency Plans

Fascinating history George. Thanks for your clarity and context.

Thanks George for laying this history out in print, it will be a great reference for Colorado River watchers.

John Orr

http://coyotegulch.blog/

Hi George,

Enjoyed the Post, but had a hard time digesting it all. For me, it was the true “Standing in front of an open fire hydrant” gushing information.

George, you are adding so much understanding to issues that are just blipping the national radar. The October issue of Smithsonian has a photo essay titled Glen Canyon Reveals Its Secrets. Lake Powell has fallen to 24% of capacity and is decreasing by half an inch a day. And we are just now noticing?

King Parākramabāhu, who resided in what is now Sri Lanka in the late 1100’s is alleged to have said “Not even a drop of water that comes from the rain must flow into the ocean without being made useful to man”. This attitude toward water use is an old one.

Something that strikes me as missing in the “compact” is the near complete diversion of tributaries. The Gila River alone takes another million acre feet per year out of the Colorado.

What would it take in terms of environmental allocation to provide a consistent flow below Morelos Dam through the bed in Mexico to the mouth? The lower Colorado once supported wetland and estuarine habitats and the people who lived in them. IMHO it should be part of any new management scheme.

Thanks for your observations, Liam. The decree from the Sri Lanka king is probably echoed in every society that reaches the precarious stage of ‘civilization’ – and the inability to ‘refine nature’ to that point of efficiency is probably why civilizations eventually implode….

The Lower Basin tributaries – Gila, Salt, Verde, Virgin et cetera are supposedly the reason for the mysterious allotment of an additional million acre-feet/year to the Lower Basin in Article III(b) of the Compact – an allotment probably hammered out in the Bishop’s Lodge bar after a late meeting, since it was never discussed openly in the meeting transcripts….

And I’ve heard that if one percent of the river’s flow were dedicated to delta restoration (with some funding from both countries for ‘gardeners’), the delta would live again…. (And ‘not even a drop’ would need to ‘flow into the ocean.’)

– G