Belated season’s greetings, dear readers! The season being the long dark days as our turning planet slowly tilts our part of the planet again toward the star we circle – moving us into a new year-cycle that will probably again be ‘one of the ten warmest years in recorded climate history’ – if not ‘the warmest’ again.

But we are officially no longer going to be concerned about that, right? The voters have spoken, with the usual one-percent victory taken by the winner to be a landslide mandate. And what the voters decided, by that one-percent margin, is that we, as a nation, the Untied States of America, shall officially cease to believe that we are changing the climate; we’ve given ourselves license to linger in the denial and anger stages – denial that it is happening, and anger at anyone who wants to blame us for that which we can now officially refuse to believe is happening.

And we will not just lie back leisurely, relaxing in our denial, doing nothing about what we believe is not happening. No, we are going to try to break all previous production records of those fossil fuels that we can now officially refuse to believe are changing the climate – yes, even coal too, to shovel into the industrial juggernaut, which will grow as all those factories that moved overseas will sheepishly return home, once the tariffs are working their magic in bending the rest of the world to our will…. We are promised this will be the official national Reality According To Trump (RATT).

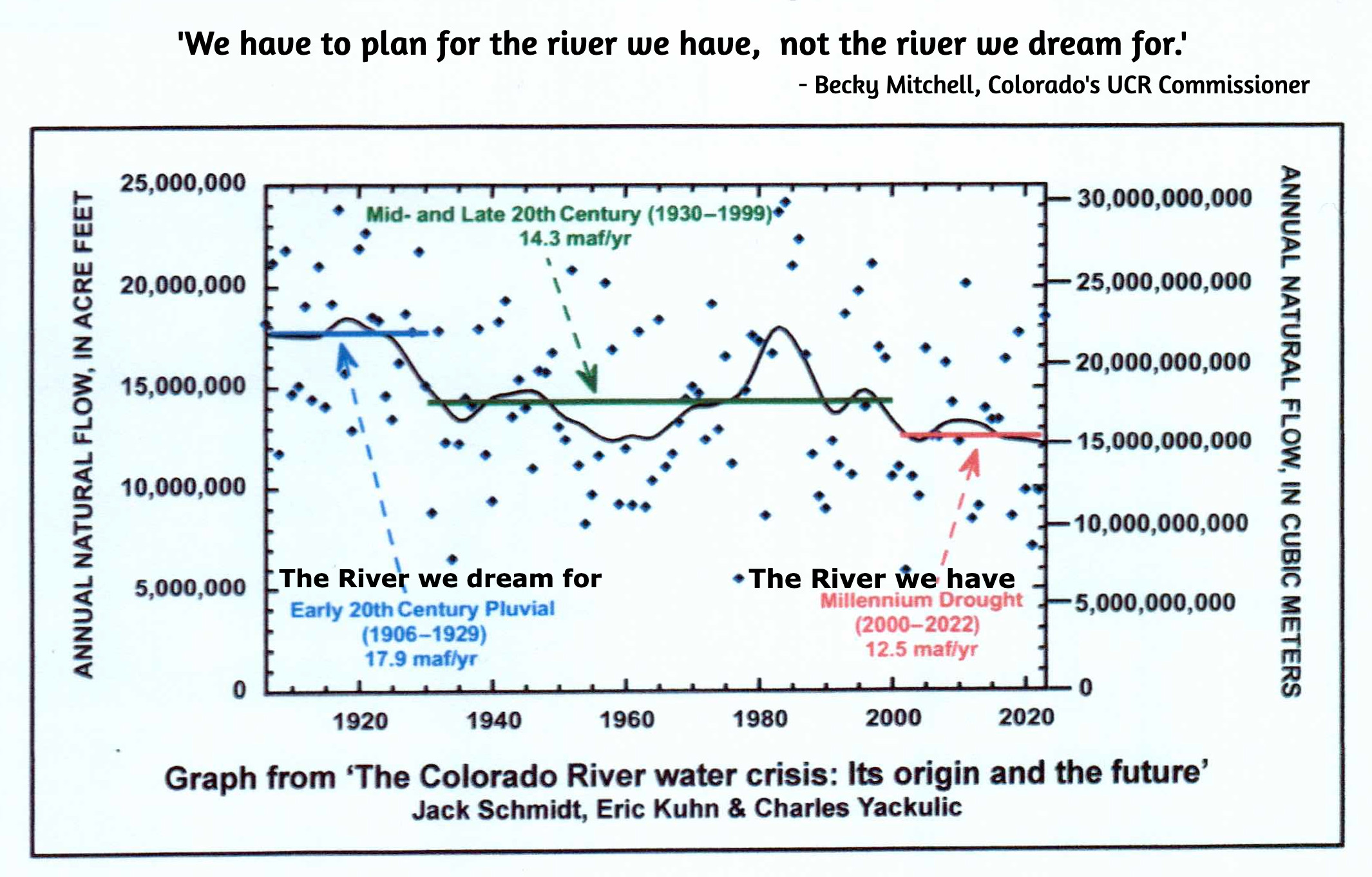

Meanwhile, however, back along the Colorado River, it is a little harder to make the RATT logic compute. The sequence of successively warmer years has had an undeniable, measurable, negative impact on our usable water supply: something like a 5-7 percent loss of surface water for every degree of rise in the annual average temperatures. It’s not necessarily that there’s less water; it’s just that more of the water is shifting into the uncontrollable vapor state rather than the manageable liquid state we earthlings need. The bottom line is a measurably diminishing supply, over the past several decades, of the surface water on which 35 million city dwellers and the irrigators of five million acres of desert land depend to some degree.

Where are we right now with the management planning process for the river? In mid-November 2024, the Bureau of Reclamation issued five mix-and-match alternatives for managing the Colorado River in the future – meaning the decade or so beyond the 2026 expiration of the 2007 Interim Guidelines (and the 2019 Interim Interim Guidelines, and the 2023 Interim Interim Interim Guidelines).

These alternatives are the Bureau’s effort to break the stalemate in the stalled negotiations between the four states of the Upper Colorado River Basin and the three states of the Lower Colorado River Basin. Large cuts in use will be necessary to keep the storage and distribution systems operational, and each Basin wants the other Basin to take a larger share of those cuts proscribed by ‘the river we have, not the river we dream for,’ as Colorado’s chief negotiator Becky Mitchell put it. (See the graphic at the beginning.)

The Bureau’s five alternatives, for which they plan to do the required Environmental Impact analysis this year, all focus primarily on managing the two main reservoirs, Mead and Powell, although other reservoirs in the system may by used to bolster storage in the two big ones. The five alternatives run a gamut from the NEPA mandatory ‘No Action’ alternative (continue business as usual), through two varying levels of federal management if the states are unable to reach a working agreement, to an alternative based primarily on a plan submitted by conservation groups, to a final alternative that is mostly pieced together from the conflicting plans proposed by the two basins, assuming the two basins can find the necessary compromises to make the two plans into one plan that might work.

All alternatives except the one by conservationists (#4) include notice that ‘there would be explicit accounting of unused/undeveloped quantified Tribal water.’ This means that the settled or decreed water rights of the First Peoples would finally be acknowledged in the river accounting, noting where and by whom their undeveloped water was being used – the first step, as one tribal member observed, in eventually either getting the water back for their own use, or getting paid by others for the continued use of their water. The First People are getting closer to being at the table. (It is worth noting that the Gila River Indian Community, south of Phoenix, is the first user organization to sign a post-2026 contract with the Bureau to leave some of its water in Mead Reservoir, water that will be conserved through projects to be funded with infrastructure money, if that survives the RATT.)

That is the broad overview; if you wish for more specifics, you can find more detailed descriptions of all five alternatives here, but there is probably no real need for us citizens to get down in the weeds of detail just yet, since we are just passive participants at that level anyway.

Instead, I want to encourage us to think on the larger level of considering alternatives not part of the Bureau’s five choices. Why not? There is, after all, a large minority of us who do not drink the small majority’s RATT kool-aid. For those of you who fit that description, my season’s greeting to you are two quotations I encountered recently that kind of rang my bell:

A voice from the dark called out,

‘The poets must give us

imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar

imagination of disaster. Peace, not only

the absence of war.’

– Denise Levertov

At present we know only that the imagination,

like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity.

– George Orwell

The first is a poet calling for poets to ‘give us imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar imagination of disaster.’ ‘Peace’ is given the negative-space definition of ‘not only the absence of war’: something more, or other, than mere truce. The ‘familiar imagination of disaster,’ on the other hand, is a major element of the RATT: a nation overrun by immigrant murderers, inflation out of control, an economy gone to hell, cities awash in crime, et cetera – that’s the virulent and violent imaginings that became the principal election strategy of the Repugnicans (as distinguished from the real but very timid Republicans). They call it ‘flooding the zone with shit,’ so much imagining of fictitious disaster that one wave of lies cannot be seriously addressed and challenged before the next wave rolls over us. This was a successful campaign strategy, with the naive cooperation of the national media serving as their trumpet: when the fact meets the RATT, print the RATT – reserving the last couple paragraphs for quotes citing the facts that contradict the RATT, thus it’s fair and balanced!

But when we come to our river – how are the poets to ‘imagine the peace’? And the call for poets does not necessarily preclude the hydrologists, politicians, water managers and others who manage ‘the river we have.’ Just to say, for example, as Becky Mitchell said, ‘We need to plan for the river we have, not the river we dream for,’ moves the discourse into the poet’s realm of analogy and metaphor, not denying but augmenting the scientist’s world of evidential causation and consequence, en route to testable hypotheses.

The second quote, however, by the author of 1984 – the book describing the fully devolved RATT worldview that we are flirting with now – cautions us that ‘the imagination, like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity.’ Is that same as saying the realm of the imagination lies in ‘thinking outside the box’? Like we keep saying we need to be doing?

Well, moving forward with that assumption – Orwell seems to be suggesting that the imagination can’t kick into gear if we are, consciously or unconsciously, holding it ‘in captivity’ inside some box of dominant conventional weltanschauung – ‘world view’ in translation, ideology, or just ‘our way of doing things.’ But the word is so much more heavily evocative in German of the mass and weight of the box, the height of the sidewalls that discouraging climbing up to look over and beyond…. Orwell was aware of the flywheel power of the boxes a society builds around itself – and the extent to which that power depends on the unquestioning, often only semi-conscious, acceptance of those who dwell within the box as ‘the way it is and that’s it.’ Even if ‘the way it is’ is not that great.

That would suggest that unleashing our imagination to such tasks as the ‘imagination of peace,’ even just regional peace along a modest and shrinking desert river, has to begin by becoming aware of the box that we need to be trying to think outside of.

What I think we have in the Colorado River region are at least two nested boxes. Whenever we hear someone intone, ‘The foundation of the Law of the River is the Colorado River Compact,’ or, ‘The Colorado River Compact cannot be (tinkered with, changed to fit reality, or discarded as irrelevant),’ we can assume that their imagination is held captive in the Colorado River Compact Box. When Becky Mitchell says, ‘We have to plan for the river we have, not the river we dream for,’ she has at least hiked herself up onto the edge of the Compact Box – a Compact that was written for a mythic river half-again larger than the river we have now. She might even be looking beyond the Compact for resolution (although she can probably not say that out loud yet).

If we hike ourselves up onto the edge of Compact Box, we will find ourselves looking at a larger and more intimidating box: the Prior Appropriation Box. This, not the Compact, is clearly the ‘foundation’ of all law regarding the use of the river: first come, first served, and seniority rules. All seven of the Colorado River states had embraced the Appropriation Doctrine as the foundation of their water law by the early 20th century. (New Mexico and Arizona did not become states until 1912.)

But those of us captive in the Compact Box tend to forget that the Compact Commission came together in 1922 to try to override the appropriation doctrine at the interstate level, among the seven states. California was growing so fast, with Arizona not far behind, that the high desert and mountain states above the river’s canyon region – growing much more slowly due to the erratic ebb and flow of the mining industry – feared there would be no unappropriated water left when they hit their stride. And none of the states really wanted a seven-state horserace of helter-skelter ‘defensive appropriation’ to avoid being left high and dry.

The water managers in the states also knew that the only way to ‘civilize’ the Colorado River was to control and store the annual spring flood of mountain snowmelt, for release as needed throughout the rest of the year. And because it was an interstate river, and because the cost of big mainstream structures was beyond their means, they knew the federal government, through its Bureau of Reclamation, would have to take a lead role in that regional development. But what they did not want was for the feds to take over all the development and operation of ‘their’ river’s water.

So the Compact Commission assembled in January of 1922 to develop an interstate compact that would ‘provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System’ – a seven-way division of the waters to give each state the right to use, in its own good time, the water needed to develop its land and resources. When a state was ready to use it, their share of the river’s water would be there for them, protected from prior appropriation by other faster-growing states.

That was the vision anyway: the ‘Compact Box’ nested in the ‘Prior Appropriation Box’ was to be an interstate refuge from the prior appropriation doctrine. ‘First come, first served’ could by the law within the states – but only up to the quantity allotted for each state.

They failed to realize that vision, however, after several days of trying – mostly for reasons of vagueness about, first, the flow of the river itself, and second, their own over-optimistic estimates of their own futures. Only the persuasive power of the federal representative on the Commission, Herbert Hoover – an engineer by training who really wanted to see the big mainstream structures built – kept them on task until they patched together, ten months later, the two-basin division for the use of the river’s water.

That substitute division was immediately rejected by the State of Arizona, and is now clearly failing at its original intent to transcend the appropriation doctrine between states: California is applying the prior appropriation doctrine against the other states in the Lower River Basin (as Arizona knew they would eventually). And the Lower Basin is threatening ‘Compact calls’ against the Upper Basin states if they do not get their 75 million acre-feet over any ten-year period as defined in Article III(d) of the Compact, as though the division into two basins had given them a big ‘prior appropriation.’

The ‘Compact Box’ is basically just a ‘shadow box,’ a failed effort to do what was really a pretty good idea – an imagination of peace among the states. The question now is: would it be possible to revive that idea of an ‘equitable division’ among the seven states – as something that is already somewhat accomplished? That’s a thread we’ll pluck at next post.

One could hope but that is probably unreasonable. At least 25 years ago Rollie Fischer saw the writing on the wall and was convinced the Compact would be, had to be, reopened. He was, of course, correct. But the Upper Basin states will have a battle for survival against the profligate Lower Basin. The Water Knife might just be a prescient forecast for a country where laws no longer mean anything and only money counts.

Right on, George! It seems to me that the current wildfire situation in Calif. captures the picture (if obtusely)/ The firefighters ran into dry fire hydrants right and left so the fire was basically kind of lelt to run it’s course. A few (repug. ) politicians have been jumping in excoriating Gov. Newsom, and even the President for letting ‘infrastructure’ degenerate so bad, that a national catastrophe resulted. I wonder how that whole problem fits in to your calculations. ken

You’re right, Ken. Maintenance and improvement of basic infrastructure is a systemic problem throughout the society. It’s harder to excoriate Biden for that since infrastructure improvement was one of his biggest ambitions – and achievements through the infrastructure measures that Repugnicans would only support if it were named something else…. Achievements that the Trumpsters will undoubtedly try to defund – the more difficult for them because quite a lot of it has been already designated for specific projects that will benefit people in a lot of congressional districts (including Repugnican districts) and people will not want that to go away…. Still, it is not going to be a focus for the Trump administration, and things will continue to get worse while money that could go toward system maintenance will instead be diverted to investor dividends. The systems on which we depend will continue to get worse, but the rich will get richer! First things first.

perspicacious as always, George. thank you

Hi George. I’m looking forward to having you lead us in plucking the next thread.

Best,

Paula Kauffman