A voice from the dark called out,

‘The poets must give us

imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar

imagination of disaster.’– Denise Levertov

We have developed the resource;

Now we have to learn how to share it.– Greg Hobbs

The Trumpster Rebellion – is it organized enough to call it a ‘Revolution’? – is making itself felt in the Colorado River Basin at this point by the hold being put on all federal funding from the two big infrastructure-related acts of the Biden administration. This included funding for the Upper Basin’s System Conservation Pilot Program, to pay farmers to leave some of their decreed water to flow down (it was hoped) to Powell Reservoirs; I believe it also included some of the money being used in the Lower Basin to pay farmers to leave a three million acre-feet of decreed water in Mead Reservoir for Water Years 2024-26. This is nothing ‘personal’ against Colorado River management; it is just collateral damage caught up in the president’s general vendetta against any achievement by the Biden administration.

We’ll see how all of this shakes out in the next few weeks, I guess, or months or years, as the legality or constitutionality of all this is worked out. On the cosmic justice level – Water Year 2025? The forecasters are saying, again, don’t get your hopes too high. But hope, that ‘thing with feathers,’ flies above that; surely we’re ripe for snow now after the longest, coldest, driest December and January in recent memory….

Meanwhile, back in the bigger, longer picture…. In the last post, trying to heist myself up at least onto the edge of the ‘Compact Box’ – the box outside of which I think we all need to try to think, if only as a creative exercise – I raised the question: might it not be possible now to do what the seven Compact commissioners really wanted to do in 1922, when they gathered in Washington the last week of January, with U.S. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover?

Remember – they had come together to try to free themselves from an interstate appropriation competition over use of the waters of the Colorado River, by effecting what their Compact preamble called an ‘equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters … to promote interstate comity (and) remove causes of present and future controversies.’

This was not strictly a ‘peace-making’ gathering; they knew they had to come to some kind of an agreement among themselves about the use of the river’s waters before the U.S. Congress would consider funding to ‘secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin’ – the last goal listed in the Compact preamble, but it was probably first in their minds. Only the federal government had the resources and the authority to build the big structures necessary to store and deliver the interstate river’s water to the states, really unleashing development of the water, at least half of which was still being ‘wasted’ to the ocean in the annual spring floods of snowmelt.

So they spent the first three days of their Washington meetings in an ultimately frustrating attempt to calculate an ‘equitable’ seven-way division of the use of the waters, to avoid a seven-way appropriation horse-race between fast-growing states like California, already at the first turn, while slower-growing states like Wyoming were still trying to get out of the starting gate.

They were stymied in that effort – almost to the point of abandoning the idea of a compact. In the manner of early 20th-century Americans, enough water for all the optimistic future visions they all brought from their home states tallied well beyond even the Bureau of Reclamation’s overly optimistic guesstimates for the flow of the river – then in its ‘pluvial’ period of high flows, peaking even as the commissioners were working in 1922.

Only Chairman Hoover’s leadership skills – and his desire (an engineer by training) to see the big structures built – kept them from abandoning the idea of a compact in January. But he wasn’t able to get them back together for serious work until November 1922, when they convened for a do-it-or-drop-it retreat at a resort near Santa Fe to consider a new idea hatched between Hoover and Colorado Commissioner and water lawyer Delph Carpenter.

In 18 transcribed meetings over 11 days, and who knows how many pre-meeting breakfast caucuses and post-meeting saloon and suite connivances, they assembled the Colorado River Compact that divided the Basin into a four-state Upper Basin above the river’s major canyons and a three-state Lower Basin below the canyons, each of which would get half of the river’s mainstem water to further divvy up in their own good time.

A hundred years later, we can see that this did very little, even at that time, ‘to promote interstate comity (and) remove causes of present and future controversies’ – Arizona would not even ratify it at the time, and it took several years for the other six states to ratify it since the mathematics of only 7.5 maf precluded some of their grand visions. And it didn’t take long for the Upper Basin states to realize that their 7.5 million acre-feet ‘half’ of the diminishing post-pluvial river was probably not there – yet the Compact committed them to making sure the Lower Basin got its ‘half.’ To halve, and have naught.

The U.S. Congress, on the other hand, was generally eager to see the river developed as part of the ongoing national drive to see the nation’s lands settled by farmers and unsettled by miners – metal miners, fuel miners, tree miners, grass miners – developing the nation’s resources, and in 1928 passed the Boulder Canyon Act that set in motion construction on Hoover Dam, the Imperial Weir Dam, and the All-American Canal – a trifecta that was completed during the Great Depression years, and by the eve of the Second World War, was turning Southern California into an economic powerhouse of wartime industry.

The Boulder Canyon Act also set the allotments for each of the Lower Basin states: 4.4 maf for California, 2.8 maf for Arizona, and 300 kaf for Nevada (most of whose development was on the Sierra side of the state, very little along its short Colorado River border). Arizona immediately sued California over those allotments, and the two states were in and out of court over that until Supreme Court decisions in 1963-64 affirmed the Compact numbers for the use of water in the river’s mainstream, but granted Arizona, and the Lower Basin states in general, full use of tributaries entering below Lee Ferry, the Upper-Lower division point, outside of mainstem accounting for the water everyone hoped would go past Lee Ferry.

The Lower Basin – abetted by the Bureau – persisted in believing that there was enough water in the river so that they could continue to write off their system losses and their half of the Mexico obligation to ‘surplus water.’ They maintained this fiction until, the early 2020s, it became obvious that they were just depleting the reservoirs. They appear to be willing now to accept that their substantial system losses have to be taken out of their share, although agreement persists in how that should happen.

The Compact obligation means that the Upper Basin states were already absorbing their losses – along with absorbing the full brunt of nature’s variability while the Lower Basin got its water regardless of Upper Basin problems. The river itself had gone from its pluvial glory of the first quarter of the century into what was its most serious dry spell until the present one; and the worst fears of the Upper Basin water managers were confirmed: there would probably only occasionally be 7.5 maf of water for them after they passed the Compact obligation on to the Lower Basin.

After World War II, the Upper Basin knew it was their turn for some development work; but first they had to create their own compact for dividing their share of the water – whatever it was. The did this between 1946 and 1948, but they did not even bother to do a four-way division in acre-feet of their alleged 7.5 maf. Instead they did percentages of whatever water they would get after meeting the Compact obligation. Still hoping, like the Lower Basin, that there would be enough ‘surplus’ – above and beyond the 15.0 maf Compact division – to handle the Mexican allotment of 1.5 maf negotiated during WW II. There’s a complex story there too, but not today.

The percentages they created for their individual shares were: 51.75% for Colorado (providing 60-70% of the river’s water), 23% for Utah, 13% for Wyoming, and 11.25% for New Mexico. Their completion of the Upper Colorado River Compact in 1948 allowed the Bureau of Reclamation and its advocates in Congress – led by Wayne Aspinall from Colorado’s West Slope – to begin the process of passing the Colorado River Storage Project. This was no longer a slam dunk for the Bureau, due to a shift in the urbanizing industrialized public, from regarding the West as raw resources, to thinking of it as a source of vacation wonder and outdoor recreation. This in turn shifted the romantic vision of the river from pedal-to-the-metal development to… environmental awareness. As America got wheels and gauranteed vacations and took to the roads, Theodore Roosevelt’s brand of conservation – respectful use without waste – shifted toward preservation of natural aesthetics. But the residual momentum of development eventually got the CRSP Act passed in 1956, and several large projects and a host of small irrigation project eventually got built. At which point, by the early1970s, not only were nearly all of the good dam sites occupied by a dam, but the Bureau began to worry that much more reservoir development would reach the point where evaporation losses were prohibitive.

By the turn of the 21st century, Justice Greg Hobbs of the Colorado Supreme Court could say publicly: ‘We have developed the resource; now we have to learn how to share it.’ Some of the readers here will remember Greg Hobbs – a poet/philosopher as well as a fine water lawyer. In this context, a poet who tried to imagine the peace the river and its users need.

Do you get the sense that, by now, a century after the Compact, with everyone in agreement that the river is not only committed but probably over-committed – we might be able to finally do the seven-way division of the waters the Compact commissioners originally wanted to do? With all seven states reluctantly, grudgingly, accepting the fact that a) the water they’ve been getting in recent years is as much water as they will ever be getting – and that b) the river flows will almost certainly be gradually declining over the rest of the century, since we are doing next to nothing to address the problem causing the decline.

How do we share this?

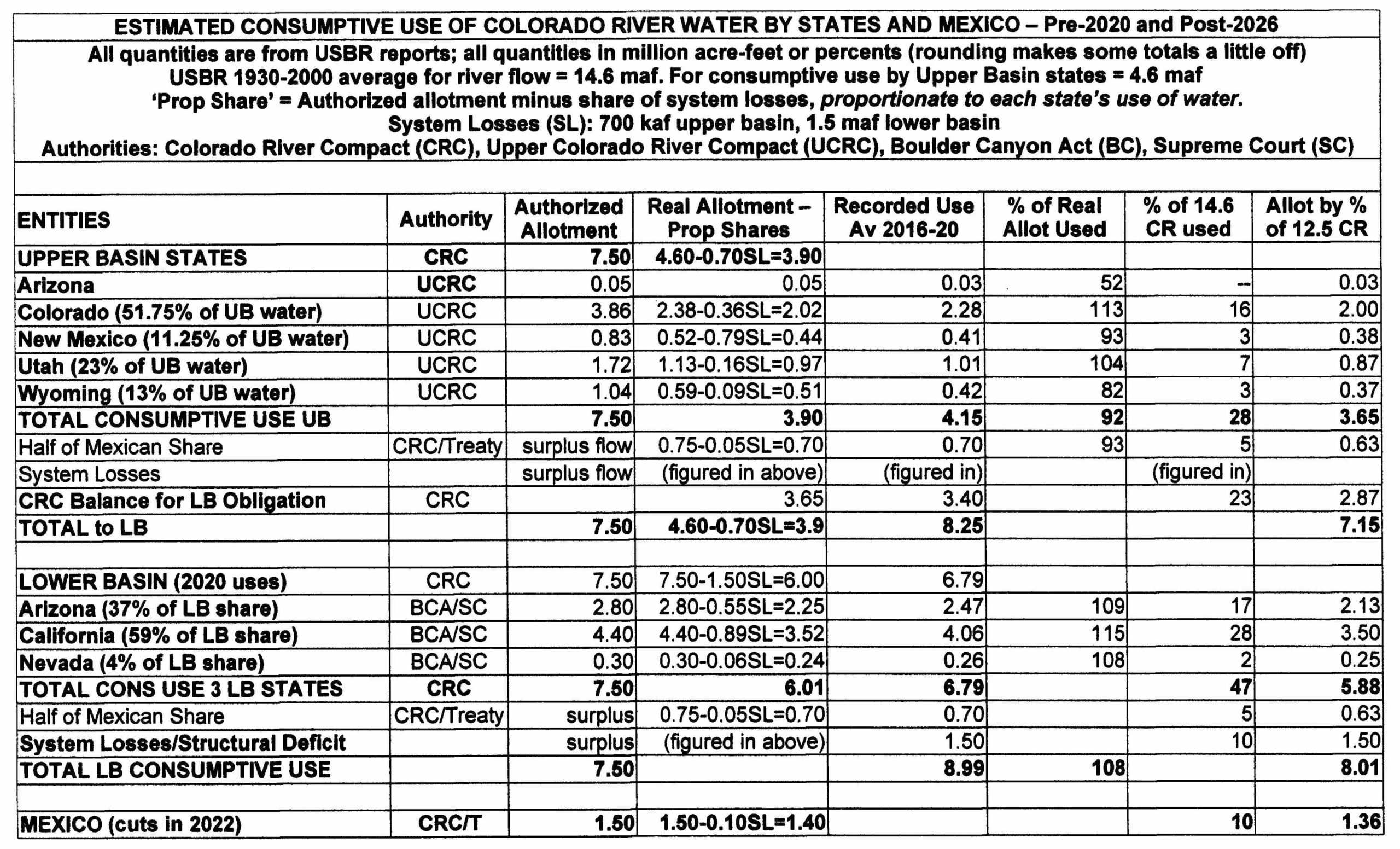

We can set it up in a table, with numbers taken from Bureau records. I know there will be disagreements over the rough calculations herein, but they will be modest differences that should not undermine the validity of the attempt – which is an attempt to say, peace, brothers, there’s nothing left to fight over; the fight is all shadow-boxing with ourselves from here on out…. Here is the table, explained below. Click on the table to get an enlargable version:

The first two columns are pretty sef-explanatory – the states in each Basin, and the authority setting their allotment for consumptive use of the Colorado River.

Third column: The allotment of the river’s water decreed to each state by the Colorado River Compact. With the river guessstimated to be running almost 18 maf/year, it was assumed that surplus flows above the allotted 15 maf would be sufficient to cover Mexico’s share and system losses (evaporation, riparian growth, et cetera).

Fourth column: The average real allotment each state got for the run of the post-Compact 20th century, minus a share of the system losses proportionate to their calculated allotment. The average flow of the river for that period ws 14.6 maf. The Lower Basin got its full Compact allotment, thanks to Article 11(d) of the Compact, while the Upper Basin calculated its ever-varying allotments in percentages of what was left after the Lower Basin obligation was discharged.

Fifth column: The measured (with some guesstimating) actual consumptive use of the river by each state and Basin circa 2020 (before the Panic of 2022).

Sixth column: The percent of their real allotment (Column 4) that each state actually used. Column 5 quantities divided by Column 4 quantities. We see that Colorado and Utah in the Upper Basin and all the states in the Lower Basin have used more than their allotments when system losses are factored in, while Wyoming is well below its allotment (a situation that may be changed by current discussions concerning the Little Snake River). But for this rough analysis, those numbers are what we will use fior projecting forward.

Seventh column: The percent of the total 14.6maf ‘20th-century’ river that each state was using consumptively. Given the diminishing flows of the river, a fair and just system for allotments for the post-2026 era would be these percentages for all states and Mexico. The sharing-out of a diminishing river should not, would not in a moral society, be done through appropriation seniority; if anything, the seniors who have been using the river longest should maybe bear the larger responsibility. The Upper Basin alone does not ‘cause the flow to be depleted’; every user, and the society in general all cause that depletion; justice decrees that the resulting pain should be shared by all, proportionate to the their use. (Greg Hobbs might not agree – wish he were here to ask.)

Eighth column: What these percentages would mean when applied to the 12.6 maf average flow of the river since 2000. Read’em and groan.

Final note, on the First People water rights: Thanks to the McCarran Amendment, those must be dealt with – and are being dealt with – at the state (and in some cases interstate) level, some through court decrees, but most of them through negotiated settlements (unfortunately requiring the approval of our dysfunctional Congress). The Upper Colorado River Commission recently committed to making sure this happens for Upper Basin nations.

And that is enough for this post, wouldn’t you say? I expect to hear a few cries of outrage that we should try to face reality in a fair and just manner.

We have to plan for the river we have, not the river we dream for.

– Becky Mitchell, Colorado Commissioner

Upper Colorado River Commission

A river can be killed by treating it only as

a commodity rather than the habitat of life itself.

When we nurture our singing and working rivers,

we celebrate the greater community in which we live.– Greg Hobbs

Ah, you AND Becky Mitchell are working with facts. That is not a world recognized by far too many these days when all you need to do is turn the valve on full force. I admire your dedication and fortitude against such odds.