In my last post, I reported that the water mavens of both the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins had each presented the Bureau of Reclamation with plans for managing the river after 2026, when the current, amended ‘Interim Guidelines’ expire.

The Interim Guidelines had been implemented in 2007, remember, when it was obvious that the patchwork of existing ‘Law of the River’ (LOTR) guidelines, laws, treaties, compacts and other measures propping up the Colorado River Compact were failing to constructively guide the extensive storage and distribution systems imposed on the river through the turn-of-the-century drought that had begun six years earlier.

The Bureau and the seven states have since cobbled together – with help from a big snowpack in the 2023 water year and a rain of cash from the Biden administration’s infrastructure acts – a set of added interim actions to stagger through the remainder of the interim to 2026. The immediate emergency out of the way, the Bureau asked the water leaders of the seven states, and of the 30 First People nations in the river basin that will no longer allow the states to ignore them, to come up with a plan for managing the river works from 2027 through – well, another interim, maybe another 20 years. In a time of climate change and political chaos, we no longer think ‘in perpetuity’ (which never worked out anyway).

So the water leaders gathered for several meetings, to try to come up with a plan for managing the river after 2027. But they were not succeeding, so the predictable happened: they went home to the two Basins established by the 1922 River Compact, and each group prepared an ‘alternative plan’ for the management of the river.

I’ve created a fairly detailed side-by-side comparison of the actions each alternative proposes when triggered by diminishing levels of storage in the reservoirs; it would not, however, be readable in the format of these posts, so you can click here to bring up a readable copy. Meanwhile, here is a summary of some of the main points, similarities and differences between the two alternatives.

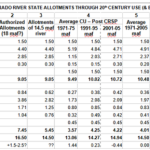

Both alternatives are similar conceptually: they operate on a measure of storage in some of the reservoirs on the river, with changes in the total content of the selected reservoirs triggering reductions in consumptive use by one or both Basins. Each alternative, however, uses a different set of reservoirs as the base – and a different date for measuring the content of the reservoirs.

The Lower Basin alternative wants the measuring standard to be the live storage of the major reservoirs in the river’s storage system: the four large Colorado River Storage Project reservoirs in the Upper Basin (Powell, Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and Navajo), and the three mainstem Lower Basin reservoirs (Mead, Mojave behind Davis Dam and Havasu behind Parker Dam) – a total of ~58 million acre-feet (maf) when they are full, which they currently are not. And they want the total system content to be measured on August 1 every year, a time when the reservoirs are still relatively full after runoff. (‘Live storage’ is the volume minus the ‘dead pools’ that cannot be delivered past the dams.)

The Upper Basin alternative wants to measure only the live storage of Mead and Powell Reservoirs, minus an undefined ‘threshold volume’ for each of them – 4.2 and 4.7 maf respectively (probably the quantity required to keep the reservoir levels up to power-generating capacity?). This would probably be in the neighborhood of 40 maf when both reservoirs are full, which they are not. And they want the annual measure to be on October 1, the beginning of the new water year, a time when storage has been somewhat depleted by agricultural use.

Both alternatives are in agreement that reductions in use have to start with the Lower Basin cutting its use by the amount of the ‘structural deficit’ – the system losses through evaporation, riparian transpiration, et cetera, a total of ~1.5 maf. This decrease starts linearly when total storage as measured by the Lower Basin drops to 70 percent of full and ramps up to 1.5 maf when/if storage drops to 58 percent. The Upper Basin alternative has the Lower Basin starting its 1.5 maf reduction when its measure of storage is at 90 percent of full, and ramps up to 1.5 maf at 70 percent. With storage, however it is measured, chronically well down in the 30 percents these days, the Lower Basin could count on leaving 1.5 maf in Mead for the foreseeable future under either alternative.

The big difference between the two alternatives comes when or if storage drops to 38 percent by the Lower Basin’s measure of total system storage, and 20 percent of Powell-Mead storage by the Upper Basin measure. At that point – basically panic time – the Lower Basin wants both Basins to begin to ramp up to an additional 2.7 maf feet of reductions, to a total of 3.9 maf – basically the 4 maf in reductions the Bureau asked for in the panicky days of 2022.

The Upper Basin, however, wants the Lower Basin to do all of the 2.7 maf in reductions, on top of the 1.5 the Lower Basin will still be doing. Their justification: if river storage drops to those levels, then the Upper Basin, much of which has no storage to rely on, will already have had reductions at least that bad imposed by nature’s ‘hydrologic shortages.’ To make them do additional reductions to send more to the reservoirs would be the equivalent of double taxation.

The Upper Basin Alternative also throws a wild card into the game; it unilaterally grants itself the prerogative to ‘undertake parallel but separate activities that are not a part of this federal action or part of the [UB] Alternative. Parallel activities refer to actions in the Upper Basin that are beyond the scope of the Post-2026 Operations, but may complement those operations.’

The ‘parallel activities’ are briefly described as (but not limited to) activities like retaining the right move waters among the big Colorado River Storage Project reservoirs under pre-existing Records of Decision, and carrying out conservation programs like the Upper Basin’s Pilot System Conservation Program that pioneered the ‘paid reductions’ that are the core of the program to get the river system through 2026 (a pilot program partly paid for by large Lower Basin organizations). It may be too much read into this a kind of ‘declaration of independence’ for the Upper Basin, but it is an independent step toward adaptive management that might make the Lower Basin, accustomed to dependable deliveries from the Upper Basin a little nervous….

And there’s one nice thing to see: both alternatives seem to bypass the Colorado River Compact mandate that the Upper Basin ‘will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below’ an annual average of 7.5 maf, come hell or low water, or the big bad Lower Basin will come after your water to make it up. When the live storage drops to the low 20 percents in both alternatives, the releases from Powell drop to 6.0 maf – with no language implying a ‘call’ on the Upper Basin if that amount is unavailable. (Not that any such language ever existed in the Compact.)

Speaking of the Colorado River Compact. Yes, we cannot escape it. It is difficult to look at this situation and not see the Compact at work, and as usual, not in a constructive way.

Forty-seven years ago, in 1977, one of the Colorado River’s droughtier years – an estimated natural flow of 5.8 maf, third lowest since measuring began – I wrote an article about the Colorado River for a magazine that wanted ‘something about the drought.’ Figuring correctly that the drought emergency would be over by the time an article would be published, I wrote a long essay about how the drought was not a problem that year for the Lower Colorado River because of the huge storage it had – but how it could be facing problems in the future if it continued uncontrolled growth. (That article, ‘The Desert Empire,’ is archived on this site.)

But one thing I observed then as a possible source of future difficulty was the political division of the river into two basins. It was only a ‘paper division’ in the Compact, but it became concrete, as it were, when Glen Canyon Dam began to fill in 1963, finally finishing filling three years after this observation about its impact in that 1977 essay:

Glen Canyon Dam backs up a body of water … which amounts to nearly the equivalent of what flows down the Colorado River in two years. The amount of water that flows out of the lake reflects not the influx from upriver but demands from downriver.

This being the case, it seems just sentimental to continue to think of the Colorado River as a single entity. For all practical purposes there are now two rivers – interdependent, to be sure, but separate, and under separate management…. To describe the two rivers in the simplest possible manner: the Upper Colorado River is generally patterned after a ‘natural’ river, with many sources and a single destination. The Lower Colorado River, on the other hand, is patterned more after, say, a municipal waterworks, with a single primary source and many destinations.

Now, a century after the Compact divided the river into two basins, and almost half a century after that observation about the post-dam river(s) – how can we look at this situation in which the water mavens from the (once) whole river sat down together to try to come up with a plan for managing the system imposed on the river(s), but after only a few days’ effort, withdrew to their ‘Upper and Lower Colorado Rivers’ to work out their River’s separate perspective on the problem? This may be the apotheosis of the Colorado River Compact, the completion of the division into two river basins whose users don’t always seem to remember they are all on the same river. Both alternatives express a willingness by their makers to reassemble as one group, but….

The natural river itself encourages this kind of separation, with a region of mostly uninhabited (if often visited) canyons constituting close to a fourth of the length of the river, separating two regions of human activity. This kind of a ‘devoid’ in the middle part of a river basin is probably just nature in the middle of some of its endless work. The river probably began as two rivers, running off the Colorado Plateau in opposite directions, that eroded into each other and are still in the contentious process of becoming one river (as soon as they are able to completely eliminate the Colorado Plateau through all their magnificent work-in-progress erosions).

The two areas of human activity above and below the canyons have evolved over the past century and a half in ways consistent with the nature of the river that runs through them. Above the canyons, mountains dropping into piedmont plateaus, carved and deposited by many small streams flowing together into larger streams, all encouraging modest scales of cultural development, by individuals or small communities, a refuge for a time for Jefferson’s and Powell’s ‘agrarian counterrevolution.’

But the other river, below the canyons, flowed out of the canyons in a powerful seasonal flood or, later, a comparative trickle, a desert river, an anomaly doing nothing for the desert but moving its silt and sand farther toward the ocean. This was a river just waiting for the Industrial Revolution, the Anthropocene juggernaut of nature transformed to the service of humankind. And that revolution arrived, late in the 19th century, growing so fast in the desert that users in the agrarian states upstream feared the entire river might be appropriated out from under them. The Compact commission resulted, to try to quell those fears enough so the Bureau of Reclamation could build the big mainstem dam that would enable California to grow even faster….

The best the Compact commission could do was the division of the river into the two basins, linked only by the mandate for the Upper River water users to not dry up the Lower River users. This did nothing but formalize that ‘natural’ division created by the canyons – and also some of the problems innate to the cultural division between the industrial revolutionaries and the agrarian counterrevolutionaries (now enjoined with the environmental and recreational groups). The long descent toward breakdown, exacerbated by climate changes we never meant to cause, has culminated in the leaders of the two basins breaking off joint negotiations over the future, and going home to their own two rivers to draft up mandates for each other.

Yet they all appear to be committed to hanging onto the Compact, like a drowning man hangs onto a straw.

Meanwhile, however, the people who were here first in the two river basins, and the canyons too, have cleared their throats, and announced again that they will not be ignored in planning the future of the river. Sixteen of the First People nations have submitted their thoughts on the future of the river to the Commissioner of Reclamation, with a list of considerations they want answers for. We will look at that next post, and maybe muse a little further on how to make one river out of two, or thirty-two. Or should we just go with two or more? Suggested reading: Go to your Trump Bible and read First Kings 3:16-28.

i love the AI image leading off the piece, George. “Well done” to the creator of it! Otherwise, a nice summary of how we got to where we are. Now I look forward to the next edition, to see what the people who were here before John Wesley Powell arrived think about the river, and what, if anything, should be done with it.

An endless soap opera in which you’ve wonderfully distilled the key contentious issues. Unfortunately, starting with a clean slate and a total watershed adaptive management system of alternatives isn’t in the political cards. George, FYI, your Desert Empire piece in Harper’s almost half a century ago was foresightful; it was required reading for my graduate Water Resource Management students at UW-MADISON

Thank you, Stephen. But I do hope we can put the Compact in better perspective as a ‘working document’ – as Hoover expressed it in the 21st Santa Fe meeting:

We finally reached, in effect, this general conclusion as to the form of the compact, and that was that none of the figures and data in our possession, or within the possibility of possession at this time were sufficient upon which we could make an equitable division of the waters of the Colorado River – (McClure inserts ‘in perpetuity’) – In perpetuity, – that we, therefore, came to this basis, not perhaps expressed by a general consensus of opinion, that there should be made by us a preliminary division to be followed by a revision at some subsequent date, – not a revision as to the preliminary quantity, just a renewed or further equitable division. That we make now, for lack of a better word, a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river. I think that is the area within which we are endeavoring to find a solution….

Not going to read a bible because no one can part these waters in any way that will please anyone as they grow and more and more scarce. What I would do is recommend ANY one reading this read your 1977 article. It is the framework for all we need to think about concerning this river.

And I broke down googled the bible verse and got tons of commentary and no actual verse. Might as well be the trump bible. My instincts remain true. There is no easy answer and EVERYONE has to compromise unless we want to live out the Water Knife tale by Paolo Bacigalupi, and that is thoroughly frightening.

Oh, the compact is the ONLY stable thing in this entire mess. Almost like a scripture it becomes someones word, right or wrong. And when written they KNEW it was wrong.

The fact that the Compact is treated like scripture – like something carved in stone and carried down off a mountain – is the real problem with the Compact, isn’t it? There’s plenty of evidence in both the Compact itself (all those ways to question, amend, and otherwise make it work) and the commentary in the Compact meeting transcripts, that its authors wanted it to be a working, adaptive instrument. ‘Cutting the baby in half’ was just an unfortunate expedient measure fostered by the nature of the ‘river-under-construction’ still trying to get itself together….

There’s another 3:16 that may come closer to the real answer.

Unfortunately, I think someone is using that one as a campaign slogan….

Brilliantly exposed, as always

Nice summary of disaster in the making slow motion. ken