In my last post, I was questioning the process of allowing the privatization of the commons through individual appropriations – in our specific instance here, privatization of the ‘water commons,’ but also of the land, and all of its living systems and the raw resources that must feed, water, shelter not just us but all life on the planet.

Every living thing that requires food, water, air or virtually anything at all ‘appropriates it from the commons,’ and probably in the strictest sense we all ‘create a property’ in the apples we pick to eat, the water we dip out of the stream to drink, the oxygen in the air we suck into our lungs. But we have not always gone on to claim personal ownership of the tree that produced the apple, or the land the tree grows on, the stream that waters the tree. That is a relatively recent invention of modern cultures – the agricultural and the industrial societies that we created when there came to be too many of us to support ourselves as hunter-gatherers living off the scattered abundance of the commons.

A contemporary writer-thinker who has considered our conduct in the commons is Garret Hardin, a 20th century American ecologist whose main concern as a scientist was the threat of overpopulation: a species (us) in swarming mode, but clever enough to stay a step ahead of the usual ‘natural’ controls – famine, plague, social breakdown and the Hobbesian ‘war of each against all.’ Hardin is best known, however, for a short excerpt, often found in high school and college texts, from a 1968 essay, ‘The Tragedy of the Commons.’

In the popular excerpt from ‘Tragedy,’ Hardin posed a grazing commons, used by a number of herdsmen. Being rational, Enlightenment individuals with a ‘natural’ desire to maximize their own self-interest through their labors, each herdsman desires to add another animal to his herd on the commons, even though he is aware that it might have a negative impact on the commons. The rational individual calculates, however, that he would get all the profit from his extra animal, while the cost to the commons would be spread among all the grazers. But with every user of the commons adding extra animals through that rational logic, the commons is over-grazed and destroyed.

This is the dark side of Enlightenment economist Adam Smith’s theory that economic individuals are driven by rational self-interest to engage in useful pursuits that will benefit their society as well as themselves, by meeting some societal need – a thesis embraced by most economists since Smith’s time (The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776).

The challenge of course is how to prevent the Enlightenment’s pursuit of individual self-interest from leading inexorably to Hardin’s ‘tragedy of the commons.’ Hardin saw the only alternatives to ecological catastrophe being either a) administration of the commons by the state or b) privatization of the commons according to the conventional wisdom of Aristotle: ‘Men pay most attention to what is their own; they care less for what is common.’ The choice between state management of what’s left of the commons, and further privatization by individuals, remains an area of open public conflict in the American West, with at least two bills before the current Congress proposing more creation from the commons.

But other modern thinkers have thought it through further – with work grounded in research, evidence collection, and other methods of the Scientific Revolution that preceded the Enlightenment. They discovered that there were (still are) many commons that have been used consistently without the users marching inexorably into Hardin’s tragedy – in some cases, in use for hundreds of years. They studied grazing commons, timber commons, fishing commons, water commons, and less tangible ‘commons’ like the air we breathe.

Foremost among these scientists is the late Elinor Ostrom, an American political scientist whose work in the study of commons was acknowledged in 2009 with a Nobel Prize in Economics. Her study of commons globally led her to observations about why some commons endured, even when used by individuals trying to maximize their own profit from their use, while individuals with the same motive degraded other commons.

Commons that succeeded over time, she found, were consciously managed locally by the users themselves, according to a set of rules generated, monitored and enforced uniformly by the users. She did not find individual self-interest incompatible with successful commons management; it was only necessary for the individuals operating on a fragile commons to be able to persuade themselves and each other that even their short-term interests required the development of rules for avoiding the over-use of their commons. And if they kept the rule-making process close to home, they would be be able to build in elements of flexibility and local control sufficient to maintain the commons without losing their own sovereignty to external forces.

It became evident, to Ostrom and to other students of the commons, that this kind of commons management had to be locally generated rather than top-down from some external authority, and among people who had similar goals in living off the commons; a community with multi-generational stability, and a ‘belief commons’ as well would be more likely to succeed in conserving its physical commons if it chose to. Equally evident was the fact that it could never be a simple one-size-fits-all process; each commons and each community would have unique features.

The ‘water commons’ – the sum of our precipitation, surface waters, and groundwater – is our interest here, and the last two years bear mute testimony to its lack of predictability, which makes management of the commons difficult, no matter what system is employed.

The acequia system of land settlement, practiced by both the indigenous Mexican cultures and the Spanish invaders, only permitted settlement by communities of people, rather than by individuals under the ‘enlightened’ Euro-American model. Acequia systems essentially have ‘commons management’ by its users built into it. Everyone works to build and maintain the irrigation system, and the watered land under the ditch is divided as equitably as possible among parciantes, with the land above the ditch being mostly an undivided commons for grazing, ‘energy production’ (wood-gathering) and timber. The system is run by its users, with both surpluses and shortages shared evenly.

The ‘enlightened’ western American water appropriation system, on the other hand, is fundamentally antithetical to even the existence, let alone the intelligent management of a water commons. The Colorado Constitution, for example, seems to establish a public ‘commons’ in first declaring the ‘water of the streams public property’ – but then immediately stating that this public property is only the water ‘not heretofore appropriated’ – and the rest of the public property is ‘dedicated to the use of the people of the state, subject to appropriation… (and) the right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied.’

Once the right to use the water has been appropriated, there is not only no encouragement to share the burden of bad years, it is actually operating outside the law to do so; the law enforces the right of the senior appropriators in a system to get all of their water, even if it dries up junior appropriators to do so. This institutes a ‘first come, first served’ system that is more competitive than cooperative.

Theoretically, the users are only appropriating the right to use the water, not the water itself, and only for so long as they actually puts the water to use. But somehow that ‘right to use’ has become a property that can be sold or bought just like any more tangible personal property. And a new owner of the ‘right to use’ can file for a change of use, then move the right to use the water and the water anywhere he or she wants along with the seniority of the right.

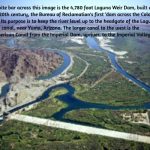

All western states in the arid region have basically the same appropriation system, with variations mostly in administration. Thus, throughout the Colorado River region, water that was appropriated and privatized for agricultural use in one place can (after a change of use) water suburban growth a couple hundred miles away in the same state – a situation facilitated by the fact that the state boundaries bear no relation to any geographic realities like watersheds. Up to five million acre-feet of water leave the Colorado River’s natural basin every year for agricultural and municipal uses outside the basin – 40 percent of the river’s water. This ‘flexibility’ of ownership, on top of its ‘first come, first served’ energy, makes the appropriation process a powerful engine for growth, but with not much of a sense of a water commons.

Which brings us more or less back to the present, where we are at something of an impasse over what passes for our water commons. The seven Colorado River Basin states are confronted with the need for a huge ‘reality adjustment’ in the way the river has been operated over the past century: essentially we must – beginning this year – abandon the magical thinking of the Early Anthropocene and cut the overall consumptive use of the river by at least two million acre-feet.

Six of the seven states have constructed a draft plan that would apportion cuts close to two million acre-feet to meet this emergency equitably among all the states – not ‘equally,’ but equitably, cleaning up some mistakes from the past, like the Lower River states ignoring a million and a half acre-feet of annual evaporation. But the seventh state, California, is holding out for strict administration of the appropriation law, which would mean they would get most of their usual allotment, 4.4 million acre-feet (minus 400,000 they are willing to put into the kitty), and Arizona, Nevada and the four Upper River states, all with water rights mostly junior to California’s, would bear the rest of the burden.

Arguments can be made both ways: the importance of the primacy of the rule of law, versus an emergency situation that the law as (mis)administered cannot resolve. I am personally of the latter persuasion (in case you hadn’t noticed), and believe the appropriation laws for water, as they have evolved, might be more part of the problem than part of the solution at this point.

There is a little-discussed fact about appropriation law and seniority rights as it is actually practiced in bad years down on the ground, at least here in the headwaters of the Upper River. That is the fact that agricultural users, at the local level, don’t like to place ‘calls’ on their neighbors in hard times – a ‘call’ being a demand by a senior user that upstream juniors let the water go by until his right is completely fulfilled.

Downstream senior users will place a call when an upstream junior is being blatant in his or her disregard for priority in a time of relatively normal flows, to bring the offender in line. But in a dry year, which is no one’s fault, farmers and ranchers who have drawn water from the same stream for years – sometimes for generations – tend to not insist on rigorous apportionment of water according to seniority, but instead sit down together and figure out how to move whatever water is available around so that everyone gets enough to avoid dead perennials and maybe get a partial crop on their best land.

The ranchers here call these ‘gentlemen’s agreements’: ad hoc measures in which humans respond to nature’s random assaults the way anthropologists show us we did for our first million or so formative years, fragile bands wandering the generally unaccommodating steppes of the Pleistocene ice ages: working it out together. Self-interest served rationally through cooperative action.

These informal agreements beyond the law seem to fit with Elinor Ostrom’s observed ‘rules’ for the long-term management of commons; ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ only seem to work at the local level where users know each other, have transcended the abstract fear that he-she-they want my water, and know that rational self-interest in living a reasonably peaceful and productive life requires some neighborly accommodation to each other’s needs, whether one loves the neighbors or not (although serious neighborhood feuds can preclude a gentlemen’s agreement).

‘Gentlemen’s agreements’ have not, however, worked when ‘upscaled’ to the state or regional level. Consider the Colorado River Compact: the seven states gathered in 1922 for the expressed purpose of dividing the consumptive use of the river’s water seven ways beyond the appropriation laws. Each state would continue to observe appropriation laws intrastate, but not interstate; they wanted a gentlemen’s agreement that fast-growing California would not be allowed to appropriate most of the river before slower-growing states really got started, and California wanted the other states to support a big-dam project on the mainstem. But either despite their rational self-interest, or on account of it, they were unable to develop that equitable apportionment. The reason they couldn’t is obvious enough from looking at the Compact meeting transcripts: the Compact commissioners were arguing from fantasies about their future development, and they would neither accept each others’ fantasies nor downsize their own, and they would have needed half again more water than even the Bureau of Reclamation’s optimistic fantasies about the river’s actual flow.

But are we now at a sufficiently different place so that the river’s reality might prevail over magical thinking? We now know how much water there actually is in the river, and approximately how much less there will be as the temperatures continue to rise; we can see that the growth energy inspired by ‘first come, first served’ is the last thing we need in the Southwest today; we are aware what a general tangle the fantasies, omissions, ambiguous language and contradictions of the Compact and the subsequent ramshackle Law of the River have created – and we know we are only a couple really bad snow years from a ‘dead pool’ status where no one below Hoover Dam gets any water at all. We know we have to come up with some kind of consensual agreement now, not after another decade in court.

Can the seven states come to the table, leaving all our fantasies of the future behind, face these realities, and come to a gentlemen’s agreement that will get us at least through the next several years with the requisite major cuts in use? While we are trying to forge some new compact that does what the last one failed to do?

If the ranchers on Tomichi Creek can do it up here in the headwaters….

‘The essence of dramatic tragedy is not unhappiness.

It resides in the solemnity of the remorseless working of things.’

– Alfred North Whitehead

This is wonderful, rooted in some commons that work. Would only more people read and understand this. Yep, it’s a form of socialism for the common good and advancement rather than the resource utilitized by the highest bidder. If there is not something for all there will ultimately be nothing for all.

It’s the guy who takes two licks from the sucker who messes it all up.

Like always, George, a provocative analysis. The concept of “commons” is new for me, but it seems to work in the context of limited resources management. Anxious for you to wave the magic wand that will be persuasive to up river and down river stakeholders.

There’s no magic wand, Carl, but one can hope new perspectives on how to look at our river will lead to new perceptions on how we might transcend the current impasse.

Hi George. I love that term, “tragedy of the commons”. I live on a park in central Denver, and I witness an example of it from my living room window twice a day when about a dozen neighbors bring their dogs to the park to run off-leash for an hour or so. They always gather in the same spot–the middle of the large meadow– and within a few months, the turf is worn down to dirt, so the park service puts up a temporary barrier to regrow the grass and the owners and dogs move to another grassy area to repeat the cycle.

It seems to me that according to Elinor Ostrom, the owners should be policing themselves, but not so.

Oh, and about The River, I haven’t seen a single article in the Denver Post in many weeks.

Thanks for another thoughtful essay.

Nice example – Elinor Ostrom would probably say they would need to start by generating their own rules for maintaining the commons, which would require them to first accept a responsibility for the commons…. ‘The what? Isn’t someone paid to be responsible for it?’

The highlight of this article ” fragile bands wandering the generally unaccommodating steppes of the Pleistocene ice ages: working it out together. “

Great column, as usual, George.

You lay it out quite reasonably. But the elephant in the dam room is capitalism, where gentlemen’s agreements rarely work. Especially in the Trump era, where taking advantage of any weakness is the road to success and power. Hard to see how the Tomichi Creek model ever gets upscaled in Boebert’s West.

All true enough. But necessity/desperation is the mother of invention, and six of the seven states are at least willing to try a different approach at this point, which wasn’t the case a year ago…. And Boebert seems to be doing all within her power to undo her West with its thin margin. We’ve got to at least try to get alternatives into the discussion when we can….

Another first-rate piece, George. Regarding Elinor Ostrom: I hope her Nobel was based on a lot more than her conclusion that “. . . ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ only seem to work at the local level, , , ” It certainly wins a Captain Renault Award. A quick note on Adam Smith: While he is often reviled for his support of capitalism, he also said that capitalists could not be trusted to act for the good of any but themselves, and government would have to keep a sharp eye on them.

I have just lately been bringing up the loss of the historical commons as a strong reason for, say, homelessness. There really is no commons, not even, as you point out via senior rights and out-of-date compacts, for river water. (I’m sure other rivers have similar arrangements, but not so publicly discussed, since the Big Red waters so many more of us.)

I remember the day, years ago now, when in the company of my perfesser pals, The Perfesser and Hobbes, when I asked, “How did the idea of the earth being owned real estate come into being,” and Hobbes mentioned Locke’s book or testament. Since then, my daughter, Marianna, has written a good deal about Capitalism, a recent bit of which covered the existence and use of the commons, a place no one owned that was available for poor people who had nothing. One day, some enterprising Coldwell Banker type must have told the king or some lord or other, “Just put a fence around it and call it YOURS.” It was done, and the commons was and still is no more.

But to think of running water not as commons but as owned? To stay in context, a bridge too far.

Thanks, George. Always worthwhile, if hopeless.

The Enclosure Acts in England did exactly that – made it legal for the lords who owned the land to kick the tenant farmers off the land and put it all in grazing sheep for the new mills (water-powered) of the early Industrial Revolution. The evicted farmers basically had two choices: go to the growing industrial cities, or – go to America, which many indentured themselves for a decade to do, then headed west for the Great American Commons – there to appropriate pieces of it as their property…. Safe, they thought, from the vagaries of life under aristocrats. See where that has gone in a world that caters to bankers….