In the last post here, I cobbled together an ‘Anthropocene variant’ on the rise and fall of civilizations, suggesting that the rise of advanced cultures was less a triumph of creative upward striving, and more a matter of beleaguered people engaging in creative problem-solving to deal with the challenge of populations outgrowing their systems for feeding and otherwise nurturing the people.

A friend from Minnesota responded with a link to a 1987 essay by American scientist and philosopher Jared Diamond that went beyond my mere skepticism about the ‘discovery of agriculture’ as a great step forward in the stories we tell ourselves. Titled ‘The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race’, Diamond argued, as did I, that people took up agriculture ‘not by choice but from necessity in order to feed their constantly growing numbers.’ He cited evidence indicating that this choice actually lowered the standard of living for the farming people, due to a reduced variety in their diet, shortage of protein, back-busting labor, et cetera.

The subsequent move on to the urbanized and industrialized ‘civilization’ stage of cultural development was pushed by the same challenge: ‘Forced to choose between limiting population or trying to increase food production,’ said Diamond, ‘we chose the latter and ended up with starvation, warfare, and tyranny.’ That choice underlay the story of the Ancestral Puebloans in the Colorado River region – and it may be the choice we are avoiding facing up to today. Welcome to the Anthropocene.

But meanwhile, back to the river in the desert, with its modest (and now shrinking) water supply – and back to the humans trying to establish themselves here….

The advanced agri-cultures of some of the First Peoples in the Colorado River region, the Ancestral Puebloans and the Hohokam, were hardly dissipated and scattered by the traumas resulting from their Holocene success, before the avatars from an even more highly developed and expansive set of European cultures crossed the Atlantic and eventually invaded this region.

First were the Spanish, working their way north from what we now call Mexico, after the audacious 1521 conquest of the Aztec empire by Cortes and his modest rogue force of conquistadores. The Spanish basically came to the New World for treasure and souls. Their charge from their king was to christianize everyone they encountered, and also to relieve them of any gold and silver or other valuables they might have for the greater glory of God and His king. In taking the natives’ souls for their god, they also put their bodies to work as slaves. It was a fairly brutal invasion and occupation.

Within a couple decades of the Conquest, their focus in the treasure hunt narrowed to the unexplored lands north of Mexico, the new presumed locus for the fabled ‘Seven Cities of Gold.’ Legends about seven fabulous cities, on an island out in the unexplored reaches of the Atlantic Ocean, had circulated in Europe since the eighth century, often mixed up with the legends of the lost continent of Atlantis. The conviction that they existed was undiminished by the ambiguity surrounding their origin, or the lack of any contact with them, or the fact that, as explorers in the 15th century ventured out into the Atlantic, the island(s) kept failing to materialize.

Once the vast North and South American continents were ‘discovered,’ it was assumed that the seven fabulous cities would eventually be found on them. And in 1537, this assumption was revived by a story so strange and atypical that it generally doesn’t make it beyond a kind of historical footnote to the Spanish invasion. So of course, in the search for the road less traveled, the overgrown door long unopened, the overlooked overlook, I’m going to tell that story – the story of the first Europeans to cross North America, Atlantic coast to Pacific coast: three white Spaniards and a black Moor.

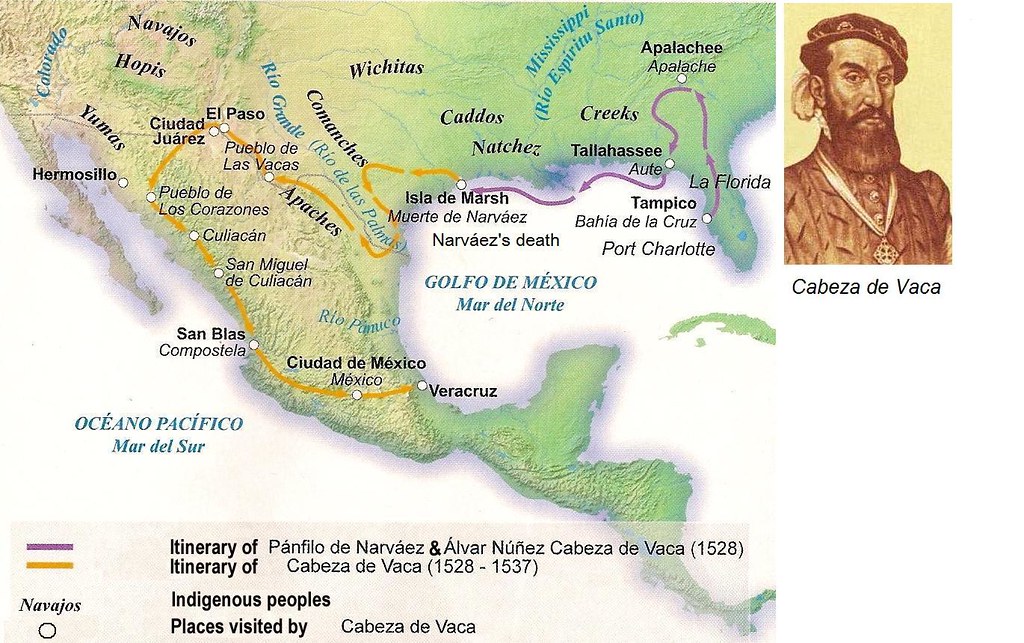

The three Spaniards were Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso de Castillo and Andres Durante, all ‘soldiers of fortune’ unfortunately part of a botched and ill-fated expedition led by Panfilo de Narvaez, a Spanish nobleman. The Moor, Estevanico, was a slave owned by Durante. Nuñez told their story in The Narrative of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca.

Their story began with a shipwreck. Narvaez was apparently a fool whose avarice and arrogance were only surpassed by his stupidity. He had been given permission by the King of Spain to settle and govern ‘Florida’ – essentially the Gulf coast and inland, from today’s Florida all the way around to the mouth of the Rio Grande. Most of Narvaez’s 600 men were lost to Indians and mosquitoes in the swamps of today’s ‘Deep South’; the four of our story were with the last eighty alive, trying to creep along the coast in their remaining storm-damaged ships to the Christian slave station of Panuco (present-day Tampico), when another storm finished off their ships and most of the men.

The four survivors were taken in by Indians who lived along the coast north of the Rio Grande; they were essentially enslaved, although the Indians were so poor that there was little status distinction: everyone worked hard to squeeze sustenance out of the difficult environment. They endured that situation for several brutal years, but gradually became strong enough again to try to get back to Christian territory. They successfully got away from their hosts/owners, and – naked and without provisions – headed south toward the Panuco slave station.

But when they got across the Rio Grande, they inexplicably turned westward, and began trekking up the river’s valley. From that point on the story took on a kind of surrealistic aspect. ‘Commending ourselves to God,’ was a frequent phrase in the Narrative from there on as they wandered westward.

They encountered numerous small clan-based bands of hunter-forager Indians, most of them even poorer than the coastal Indians. The Indians did not know what to make of these naked, unarmed and half-starved strangers, differently colored, and the intrepid four had little choice but to appear friendly and harmless. No standard-practice reading of the Requirimento in Latin to the natives, commanding them to become Christians and subjects of the King of Spain, upon pain of death if they refused.

In gratitude for food, they began practicing some basic first aid with the Indians, cleaning and treating cuts and other injuries. And when the Indians brought larger health problems to them, they began laying on hands and mumbling Pater Nosters over them – with remarkable success. A reputation as healers grew and went out ahead of them as they proceeded on their strange westward quest.

Nuñez noted that change in his Narrative, and the important role that the slave Estevan – apparently a gregarious extrovert – began to take on:

‘We exercised great authority over (the Indians), and carried ourselves with much gravity, and, in order to maintain it, spoke very little to them. It was the Negro who talked to them all the time; he inquired about the road we should follow, the villages – in short, about everything we wished to know….’

As they plodded westward – sometimes northwest, sometimes southwest, but always westward – they began to pick up an entourage, Indians who left their uninspiring lives to follow them. After two years and more than a thousand miles of trekking ever west, they had several hundred Indians accompanying them.

Then they came upon an area of burned-out native villages, and realized they were back among the Christians – and realized also that their entourage was in serious danger of becoming slaves to the Spanish. They told them to return to their villages, but most refused.

The Spanish soldiers they encountered were as nonplussed to see them as the Indians had been – still as naked as the natives and looking nothing like the Spanish gentlemen they claimed to be. Once they were again attired and fed, and their story more or less believed, Nuñez worked to exact a promise from the soldiers that their followers would be allowed to return to their homes. A promise probably honored only until the three of them were on their way to Mexico City, for an audience with the Mexican Viceroy.

But think for a moment on their journey: the first transcontinental Atlantic-to-Pacific journey by the European invaders – and they did it without killing a single native, evicting anyone from their land, or looting anything. What food they were given, they shared with their followers. It was probably the most truly Christian adventure in the entire history of the Euro-American experience.

But that is not the end of the story. Somehow their return sparked a revival of the story of the Seven Cities of Gold – and located them somewhere to the north of Mexico. This was definitely not a consequence of the report to the Viceroy by the three Spaniards, and Nuñez never mentions the Seven Cities in his Narrative. When the Viceroy heard that their journey was associated with rumors of the Seven Cities, he asked the three to lead an exploratory expedition into el Norte, but they pled ignorance and would have nothing to do with it.

That left as the source of the new rumors – Estevan the Moor. He was again a slave, after a two-year trip when he was not just a peer with the white Spaniards but was their guide, their shepherd – a lifelong survivor himself, he was probably most of the reason the four of them survived at all.

Like most hunter-foragers, or just foragers, the Indians they had encountered had a shamanic spiritual relationship with the universe – faith in ‘witch doctors,’ to the Christians. Nuñez also observed that ‘in this whole country they make themselves drunk by a certain smoke for which they give all they have.’ He does not say whether the three Spaniards indulged in this smoke, but I suspect they didn’t, in their efforts to maintain their godly distancing.

Estevan, on the other hand – we can imagine him around a small fire with his hosts and a head full of smoke, trying to converse with some shamanic figure in from the vast despoblado, a brown-skinned Merlin whose shadow-travels had taken in all the landscapes of time as well as space, all the dry gulches and unexplored arroyos of might-have-been and might-yet-be…. Imagine Estevan asking about the kinds of riches the Spaniards were interested in, and the shaman, understanding either not at all or too well, making a broad narcotically amplified gesture toward – well, toward what? El Norte or tomorrow? The past or Arizona? Confusion on the specifics, but Estevan had enough imagination to fill in the blanks – places out there, great cities alive with light, cities of gold, cities of the sun…. (I realize I am taking liberties, but I’m a mythologist, not an archaeologist.)

Before leaving to return to Spain, Andres Dorante had given his slave Estevan to the Viceroy, which gave Estevan the ear of the King. There he planted the seeds that relocated the legendary Seven Cities of Gold from an island in the Atlantic to a land somewhere beyond the deserts of northern Mexico. All Estevan probably wanted, really, was to get back beyond civilization where he was something more than just a slave, and he saw opportunity in firing up the materialistic imaginations of the Spaniards.

The Viceroy organized an exploratory expedition in 1538 led by an adventurous Franciscan friar, Marcos de Nizza, to check out Estevan’s story, and sent Estevan along as guide. The expedition turned out badly. Estevan – who showed up for the departure in a feather cloak with bells on his ankles – overplayed his hand, especially with the native women, and was killed in the first pueblo encountered, a Zuni town of stone and adobe with little in the way of riches. Fr. Marcos chose to not actually go to the pueblo but claimed to have seen it – maybe with a bit of a glow at sunset – and returned to report that, indeed, it might have been a ‘city of gold.’

This inspired, a year later, the massive 1540 Coronado expedition that went out with around 2,000 soldiers, Mexican Indians, Franciscans, and herds of horses and cattle, charged with finding and claiming for the King the Seven Cities of Gold. Coronado found the Zuni pueblo where Estevan had been killed, and ascertaining that it was no City of Gold, went on to other similar pueblos in the Colorado River Basin, where they also ‘discovered’ the Grand Canyon. The expedition then veered east and eventually made its way into the Great Plains, finally giving up the search somewhere in the vast grasslands of present-day Kansas, and returning after two years to Mexico City.

The Spanish-Americans gave up on the northern search for the Seven Cities of Gold after that; but around 1600, looking for souls to christianize and bodies to put to work, they pushed up into the middle Rio Grande Basin and the Gila River tributaries in the Colorado River Basin, and created ‘unsettlements’ there. Later, in the 18th and early 19th centuries they pushed a string of missions up through Alta California, as far north as the San Francisco area.

They maintained a quasi-military presence in El Norte, partly because the natives they tried to control did not appreciate working for a god and king not their own, and partly because of natives they could not control – the Apaches, Comanches, Utes and Paiutes. The great gift the Spanish gave the native peoples of the Americas was the horse – horses that escaped, went wild, and were caught by the Indians, who took to them like Americans took to the automobile. They became better horse soldiers than the armor-laden Spanish, and maintained their own turf by terrorizing any efforts to create farming settlements in it. A presidio or fort at the present site of Tucson was their Colorado Basin base, as was the town of Santa Fe in the Rio Grande valley.

In the early 1800s, the native people of Mexico finally had their fill of the Spanish, and ran them out in a revolution that concluded in 1821. The territory all the way to the 42nd parallel became part of the United Mexican States – but that ended a mere 27 years later, with the conclusion of the territorial fight picked by the United States to the north, and everything north of the Gila River and the Rio Grande was ceded. We’ll look more closely at these transitions down the road here.

But what of the Seven Cities of Gold? Perhaps the shamanic Estevan was just running ahead of time. The Euro-Americans who invaded and overran the Spanish-Americans in the Colorado River region also had a vision of great cities – but for them, it was a do-it-yourselves project, which they fell to with a will in the 20th century, using the river to water their vision. Los Angeles-San Diego, Las Vegas, Phoenix-Tucson, Albuquerque-Santa Fe, Denver-Pueblo, Salt Lake City-Provo, and coming along slower, Cheyenne-Laramie…. They’re no longer gold; they’re just money now – but that’s a story for another time.

Next time – reflections on the real American Revolution I promised for this post, but I got distracted by Estevan.