Going up to the East River valley this week, a tributary to the Gunnison and eventually the Colorado River. But no lecture today. I realize I’ve been pontificating a little in these postings. My Gunnison friend Mike calls me ‘Perfesser’ – which harks up memories from fifty years ago of my first editor, also named Mike, at the Mountain Gazette, who occasionally opened his critique of something I’d submitted by observing that ‘this one came from Uncle George the Pedant’…

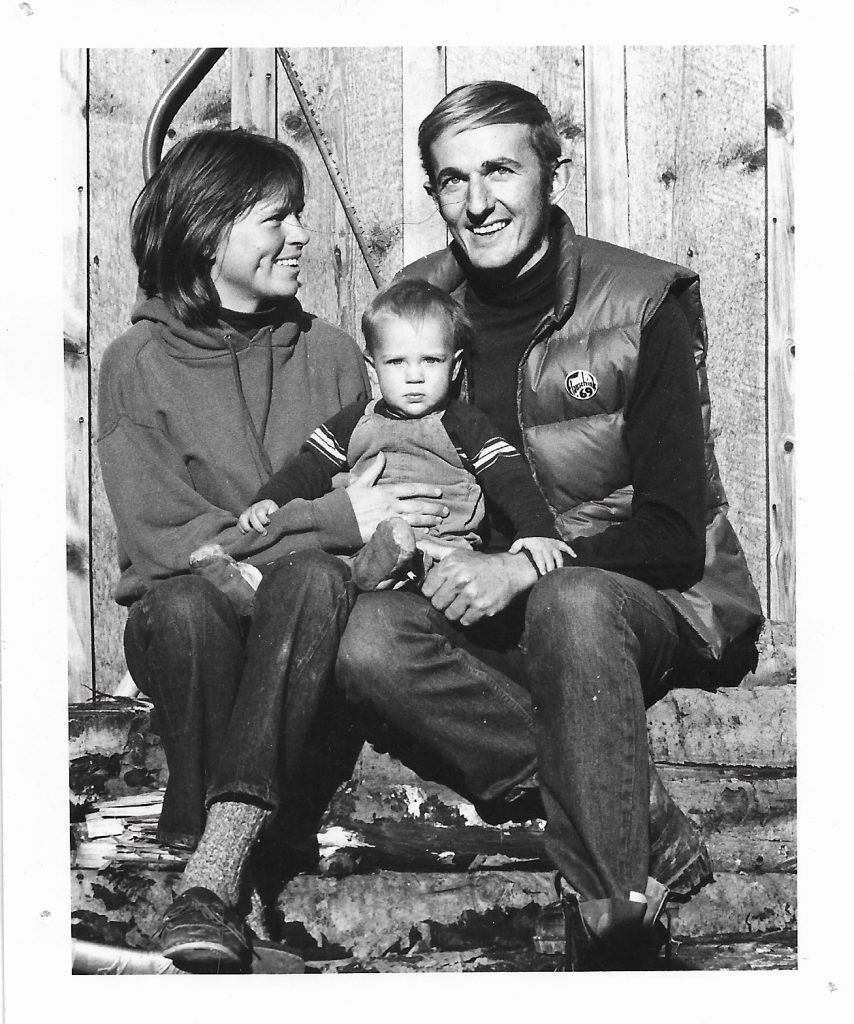

So this week I’m just reflecting on an experience from fifty years ago. I realized that the winter of 2021-22 is the 50th anniversary of a move, with my partner then Barbara and our 8-month-old son Sam, from downtown Crested Butte eight miles up the road to the old townsite of Gothic in the valley of the East River, to be the winter caretakers for the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL, pronounced ‘rumble’ locally).

Barbara and I at the time were both a little burned out on what we had been doing – carving wooden signs for her, putting out the newspaper for me, and too much volunteer time for both of us working for the future glory of Crested Butte – and we were also more or less broke, chronically. So we were thinking about retreating for a while to Denver or maybe Boston – don’t ask why – to get real jobs and make some money, or failing that, go to graduate school on government loans and get some ‘real-world’ credentials for getting real jobs to make some money, et cetera.

But then one evening, discussing with friends where we might go and why, over spaghetti and Carlos Rossi, it kind of popped into my mind, then out of my mouth: ‘What I’d really like to do is persuade RMBL that they need winter caretakers, then apply for the job and move up there for the winter.’ Barbara looked at me, shocked, having heard nothing of this – then said, ‘What a great idea!’

It did require talking RMBL into the idea, but this wasn’t hard because more people were beginning to venture into the high country, winter as well as summer, and they had found evidence that back-country skiers had broken into a couple of their cabins the previous winter – nothing stolen, but big fires built in old stoves in cabins never intended for cold weather use, and freeze-dried debris left behind. We put the caretaker idea to Chris Johnson, RMBL director and a good friend, and he decided it was a good idea, so long as it wouldn’t cost RMBL anything.

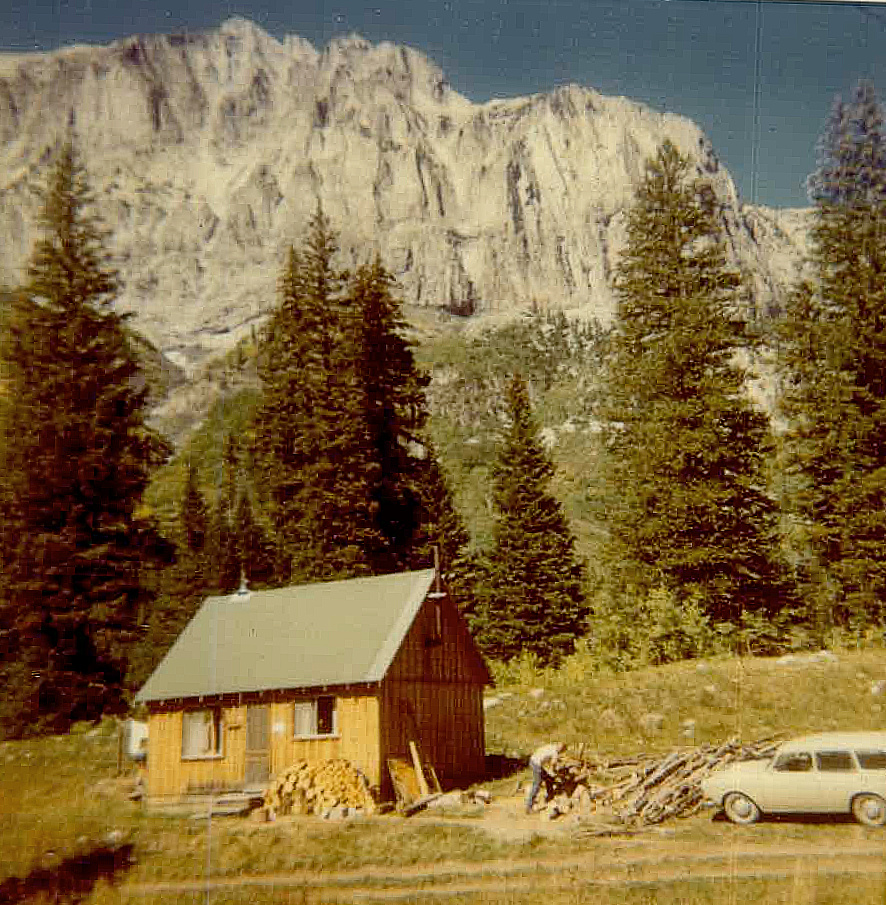

So instead of returning from the edge of civilization to one of its centers, we surprised ourselves by moving a few miles beyond the edge. Early in September 1971, we settled into a 16 by 20 cabin on the sunny side of Gothic, which I winterized to the extent that we could afford – some one-inch foam insulation fitted into the spaces between studs, and 3-1/2-inch pink insulation stapled into the rafters overhead. Overall, probably an R factor of about 7.

We had a strange mix of ‘conveniences’ – we had electricity, a countertop refrigerator, and a gas stove with extra propane tanks out back, but the ‘central heating’ was a potbelly stove that burned wood or coal. (It is unimaginable today, but RMBL then had a pile of lump coal for their summer scientists to use when the monsoons socked in for a couple three days.)

Since Gothic was five miles beyond where the snowplows stopped plowing, we left our car in a friend’s driveway in Mt. Crested Butte and traveled on skis from there.

There was no indoor plumbing. Gothic had a water system but it was for summer use only – pipes buried only a few inches deep, if at all. There was, however, a covered spring a couple hundred feet up from the cabin; the Gothic scientists were pretty sure that it ran year round. And there was a lovely south-facing outhouse a mere 50 feet from the cabin, with an indoor thundermug for night needs.

This was, however, no Thoreauvian exercise in self-sufficiency. We were, if anything, more conscious out there of our near-total dependence on a large, wealthy and maybe a little indulgent civilization. We had enough money to lay in a winter supply of ‘heavy goods’ – cases of canned soup and vegetables and condensed milk, bags of brown rice and beans, flour and sugar and other staples, a couple 30-pound boxes of peanuts for the protein, and a few cases of Carlos Rossi’s finest. We did not become total vegetarians there, but we reduced our meat consumption considerably – a chicken brought back from town would last a week at least, counting the soup from scraps and bones.

All told, it looked like living rough, and most of our friends thought we were absolutely crazy – maybe even borderline criminal crazy, taking a seven-month-old baby into such a situation. Other friends would get a kind of a faraway look in their eyes when we told them what we were doing, and we realized it wasn’t our idea alone. We reminded the critics that we’d all come from ancestors not that far back who had lived that way, or worse, and survived, even thrived – and we had the advantage of electricity.

We quickly settled in a routine, once there: I had my old rolltop desk from Crested Butte’s ‘Big Mine’ office in one corner of the cabin; Barbara worked on her woodcarving at the cabin’s table, with the chips brushed off into the woodstove at dinner time. Sam had to put up with two parents 24/7, but didn’t seem to suffer from it. And from the 50-year perspective, I think it was a much saner existence out there in the wilds than we would ever have found back in the hard heart of civilization.

Morning was work time; early afternoon was chore time, chop wood, haul water. We had a beautiful Indian Summer that year, and spent most of those afternoons out gathering firewood, taking Sam along to watch. We didn’t have a chain saw, so were limited mostly to aspen that we could cut up with a bowsaw. RMBL let us use their ancient pickup truck, which we would fill up with eight-foot lengths, to saw up later at the cabin. (See the picture – note also the tidy stack of wood by the door where snow sliding off the roof would eventually bury it.)

There are certainly worse ways to spend fall afternoons than out among aspen, in their almost psychedelic transition from green to gold. And with the bowsaw rather than a chainsaw, our presence there was more of an infiltration than an assault; so long as we left the living alone and just took the dead, the trees continued their own conversations amid their business of preparing for the winter. The bowsaw also kept us in shape.

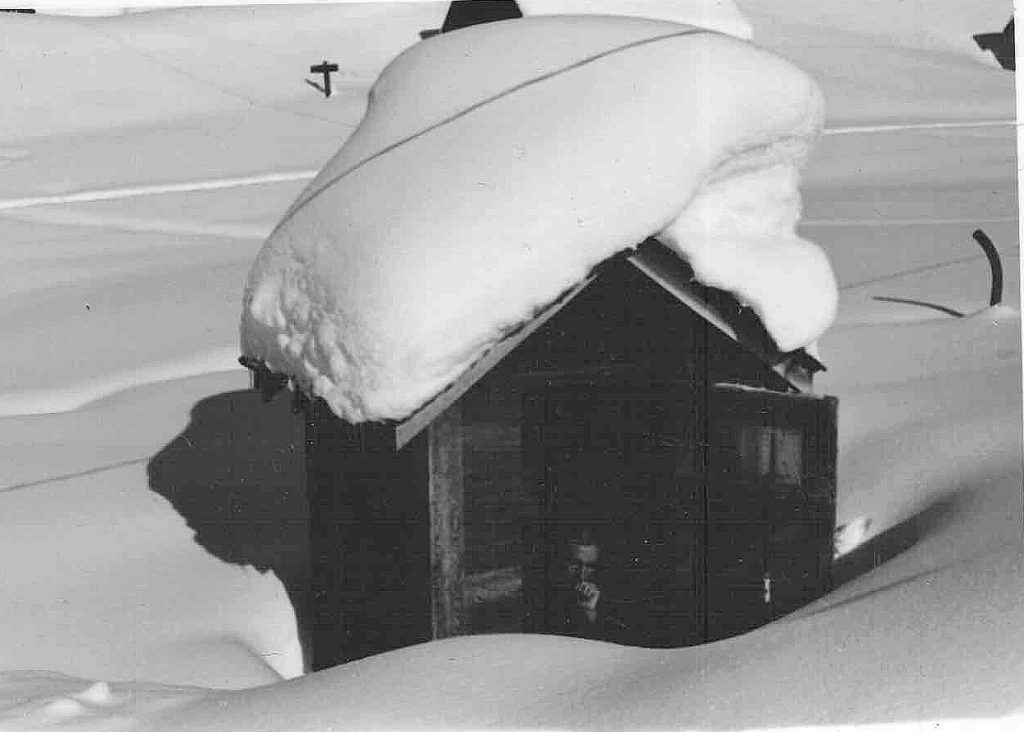

Woodhauling with the pickup lasted into November that year, but then the snow started coming – no huge storm to launch the snowpack that year, just a series of six or eight inch storms that eventually made it time to park the pickup for the winter.

From then on, chores were done on the ‘webs’ – snowshoes – I’d bought at Tony Mihelich’s Hardware. That was about 40 years before showshoeing on sleek lightweight aluminum snowshoes became popular. The webs I got from Tony had wood frames with strips of some kind of animal hide for the webbing, all of it heavily shellacked. They were neither sleek nor lightweight. The comparison to our Nordic skis for traveling was the comparison of a Ford Mustang to a Farmall tractor, but for chores around the cabin, the tractor was what we needed.

Once the snow began to pile up, we realized the freedom we had from living our lives at street level; with no automobile, we could live on the surface of the snow. We only had to shovel up to the surface from our entry doors; then we used the snowshoes to pack out nice 18 inch wide trails to the spring box, the outhouse, the sawbuck. After a couple days of sun, those trails would be firm enough to walk on with just our boots, until the next storm and the need to repack them with the snowshoes. That worked anywy until the snowpack started to melt; as the snow ‘rotted,’ the paths became treacherous and we needed the snowshoes.

I also used the snowshoes to gather more wood. We had quite a bit stacked, but I was sure it wasn’t enough (there is no such thing as ‘enough firewood’), so I began going out into the woods above Gothic on nice days with a rope harness and the bowsaw, and finding a couple three- or four-inch diameter dead standing aspens to rope up whole and drag down to the cabin to saw up.

For water, we used two five-gallon jugs with spigots filled at the springbox. The spring – which did run all winter – was the emergence of ‘interflow,’ snowmelt that had sunk in farther upslope and come briefly back to the surface, where it was captured in a pool about two feet square, six or eight inches deep. Spill from the spring ran on the surface for a few feet, then disappeared back underground, eventually making its way to the East River as groundwater if it wasn’t consumed by trees en route.

The jug-filling process was thoroughly inefficient – sitting on the stone edge of the box dipping up a panful and pouring it through a funnel into the jug. But the tedium of that was relieved by the fact that one could keep an eye on Gothic Mountain, presiding over the valley. Even when the weather was bad, the mountain was there – in parts and glimpses, making it even more of a presence. Once the snow was on it, there were days at the springbox when I could not tell where the mountain ended and the sky began.

We used around five gallons on a normal day, which meant usually filling one jug a day; but laundry day used both jugs. It’s surprising how little water a household really needs when there are no flush toilets, and basin baths (using Barbara’s big bread bowl) substitute for showers. Enjoy those luxuries while you still can.

One or the other of us skied to town about once a week, in and back (usually) before dark, to get the week’s mail, a dozen eggs, some fresh greens, and maybe a chicken or pot roast. Occasionally we would all three go to town for an overnighter. For Sam, I built a box from scrap lumber that I mounted on the plastic toboggan we used to bring the water jugs from the springbox. Sam, heavily swaddled, usually slept most of the way to town, despite the incredible surroundings.

Our friends’ (and our own) worst fears were unrealized; it was a vigorous and occasionally rigorous life, but in a place of unparalleled beauty and quiet magnificence that both embraced and challenged us. I remember the stillness of the valley, which was not quite a calm – we knew the ermine was down in the tunnels under the snow terrorizing the field mice, the coyote would be somewhere stalking the hare. It was the stillness of waiting, the quiet just before.

I remember – must never forget – going out to the outhouse before bed one night, grumping a little to myself at the inconvenience of no indoor toilet; then being kind of gobsmacked by the night, stopped by the night on the path to just look at it all. I was for the moment part of a great flower, the mountains rising around us like petals, us just stamens deep in the flower, praying to be dusted by the whitefire pollen spread across the sky…. Gothic and the East River valley can confront and comfort simultaneously.

We liked it so much that we stayed for four winters, working the summers between winters as general RMBL staff – enjoying the focused busyness of 150 people engaged in serious science, learning more about the place ourselves just talking to them. But we were also glad as they began to leave in August and early September, and it was our place again, to be buttoned down for the winter, mattresses put in mouse-proof storage, shutters put on upslope windows, et cetera.

We had to leave after our fourth winter. Daughter Sarah had joined us by then – born in the cabin the previous summer, another story in itself. She was still small enough so I could build a longer box for the toboggan, one kid at each end. But that would not have worked for another winter, and we had neither the means nor the desire to ‘mechanize’ with snowmobiles. So we went back to civilization, in about the same marginal economic condition as when we’d left for Gothic, but incredibly enriched by having had the blessing of being there. I joke that it ‘ruined me for civilization’ – but fifty years later, I’m even more inclined to say it’s not entirely a joke.