Back (almost) to the present, in this meandering journey over the life and times of the Colorado River region. This is a followup on the last post, which posed the perspective that the westward expansion of Western Civilization across North America was a territorial contention between two big cultural paradigms. Dominating the contention was the fossil-fueled Industrial Revolution out to convert the vast resources of the continent into economic wealth for all who were willing to ‘help themselves.’ The other idea in play was an Agrarian Counterrevolution of locally sufficient farming communities with more modest but less articulated ideas of the rich life, mostly trying to stay ahead of the Industrial Revolution and out of its way as they fumbled toward Thomas Jefferson’s semi-articulated vision of a decentralized grassroots democracy run by a ‘natural aristocracy’ of educated farmer-citizens.

In the (un)settling of the west slopes of the Southern Rockies – the headwaters of the Colorado River – the Anglo-European invasion came mostly from the east over the Continental Divide, and worked its way down the mountain valleys to the high desert of the Colorado Plateau and the Great Basin. Because the mountains were where the gold and silver were, the Industrial Revolutionaries stayed up there, but the Agrarian Counterrevolutionaries headed down to the floodplains of the Upper Colorado River and its tributaries as soon as the Ute Indians were moved out of region and onto a couple small reservations in 1881.

The Agrarian Counterrevolution was thus able to establish itself somewhat in areas of minor interest to the Industrial Revolution into those downvalley reaches of many Colorado River tributaries. Had Jefferson still been around to see what developed in the valley of the North Fork of the Gunnison River in the late 19th century and early 20th, he might have said – Yes! That’s what I mean!

This is a story from the ‘North Fork country’ – which also is generally taken to include the Smith Fork and Crystal Creek valleys that fall independently into the Gunnison River, to the south of the North Fork.

It is also my memorial for two men from there who bent my course for the better, who both passed on this past year.

In my checkered career as freelance writer and general oddjobber, I once spent a few years running the saw in a small sawmill in the Crystal Creek valley, a relatively wild tributary of the Gunnison River that plunged into the Black Canyon of the Gunnison in a waterfall a few hundred yards from the sawmill. A relatively modern cabin (indoor plumbing) came with the sawmill job; from the bedroom window we could see the far rock wall of the Black Canyon.

As a middle-class petit bourgeois, I’d been conditioned from first grade to go to college so I wouldn’t ‘end up working in the mill.’ I went to college, learning large ideas but little of use – and still found myself ‘working in the mill’ at around age 35. But what surprised me, working in that sawmill, was the dawning realization that it was one of the most expansive learning experiences of my life.

The job was a bridge over an apparent contradiction in my life: I was a lover of trees, but oddjobbing as a carpenter had made me a lover of good boards, and I knew the one-way relationship between trees and boards. But what I gradually learned running the saw was how to get the best boards possible out of the trees our logger brought in – every tree, like every person, an individual shaped by its unique responses to its environment. It was a serious responsibility to read each log’s personality, the ways in which life had subtly favored or warped it, and to cut it accordingly so a minimum of its warps and flaws were transmitted into boards to be cussed at by carpenters.

But beyond that – the sawmill was my first introduction to ‘the Other America,’ the Agrarian Counterrevolution. There are still pockets where the Agrarian Counterrevolution did establish itself somewhat, not necessarily in a well-articulated way, but the spirit of an Other America is there, and that sawmill was one of those places – thanks to the two men I want to re-member here….

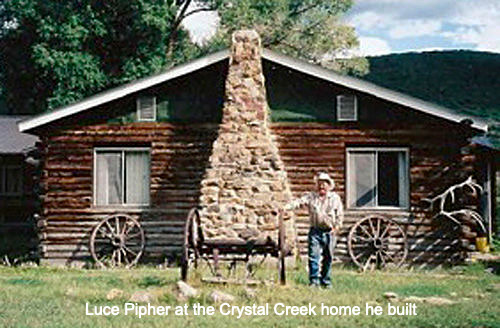

The owner of the sawmill was Luce Pipher, son of one of the wild men that hung out in the edges of the industrializing West – not exactly, or not yet, an outlaw, but never fully corralled either. Luce’s father ran the kind of barefoot and bareknuckle porefarm where they stopped feeding you when you got to your middle teens, so Luce left home then, but came back a few years later and bought out his father.

Cattle ranching was Pipher’s first love, but he was philosophically opposed to contracting a grazing lease with the federal government. Rather than pulling a Bundy scam and just taking the public grass, he leased what he needed from private landowners in the Smith Fork and Crystal valleys.

He also knew that a business whose markets were organized and controlled out in the cities of the plain was vulnerable down on the ground, so he got all kinds of things going on the side to support the ranching operation, and the sawmill was one of those things – a little two or three person operation capable of cutting a couple hundred-thousand board feet of rough-sawn, sun-dried lumber a year, but as he said, ‘You always have a few dollars in your pocket.’ (Another Pipher financialism: ‘I’ll never have a million dollars, so I’m gonna try to die owing a million.’)

He was the kind of man who pretty literally threw himself into whatever he was doing, sometimes without thoroughly strategizing the operation his mind was throwing the body into, and when I knew him, he walked with a gimp from getting a leg pulverized in a mill belt, and he had a face that looked like it had been kicked by a horse, which it had, almost killing him. He worked, played and lived hard.

Because I was born and bred in a civilization that equates the good and beautiful with ‘shiny and new,’ I underestimated the sawmill when I first saw it. By civilized aesthetic standards – the first eyes I saw it through – it was not beautiful. A cobbled-together, unadorned assemblage of unmatched parts, it only became beautiful when you turned it all on and it all went to work. Pipher told me, with a pride that at first puzzled me, that it was all assembled from ‘junk.’

‘Junk,’ I came to learn, was a tricky but important word around Pipher. A former employee of the mill told me that Pipher had fired a man once for muttering something about ‘junk’ while working on a breakdown. But Pipher himself used the term frequently and freely, often with a liberal salting of deletable expletives. And he used it once with me, when I’d made a comment about not just the antiquity but hypothetical parentage of an old Hough front-loader we were trying to resurrect for use in the logyard.

‘The trouble with you damn hippies,’ he said, ‘you just don’t understand junk.’ So if you were going to use the term, you’d better understand what it meant.

Over the two-plus years I worked at that sawmill, I gained at least a journeyman’s appreciation of junk. Pipher himself was a good junk artist, but his son Luther was better. There was a big unheated shop building near the sawmill that was Luther’s domain – a creative mess with some really fine metal-working machinery buried here and there in the – junk.

One day I was working on our Volkswagen – always a cause for snickers there in Ford and Chevy country. Luther was hanging around watching when I finally located my problem: the fork that disengaged the clutch was worn out. ‘Probably take a month to get one of these,’ I grumped.

After the obligatory commentary on foreign cars, Luther looked at the piece, then looked at where it fit and what it needed to do, and went into the shop. He scuffed around in the junk, picked up a few scraps of metal, went to work with the machines and welder, and in less than an hour, had assembled a new clutch fork for the Volksie that was still working when I sold it five years later.

The accumulation of ‘junk’ that had been transformed into a sawmill functioned just as beautifully, however plain it looked. It was the work of another junk artist, and the second man I want to re-member here: Ken Spencer from Crawford down the road in the Smith Fork valley. The mill, to the best of my knowledge, had nothing purchased new except for the teeth I put in the saw when the old ones were ground down. It was all assembled from secondhand stuff from salvage yards and those private EAR collections (Equipment Awaiting Repair) that adorn every farm or ranch that has been around long enough to be worthy of the name. Junk might be one of the most reliable products of farming. ‘If you need a piece of wire,’ Pipher said one day (shaking off a piece caught on his boot), ‘just take ten steps in any direction.’

But junk is just junk until somebody comes along who knows how to work with it, a junk artist to beat off the rust and coax it back into action. Ken Spencer had built the mill for his own Crawford business, Spencer Lumber Company & Sawmill; but he’d put it up for sale because he got the idea for an even smaller mill he could mount on a semi trailer, to cut aspen for a specialty market he’d discovered.

Pipher acquired the mill because he knew how good Spencer was at resurrecting junk. Give him a cutting torch, welder, grinder, some hand tools, a big box of bolts and nuts, and the cultural resources in the local EAR yards, and as a last resort authority to buy a few specialty parts, and he would come up with a usable version of anything you needed, from a sawmill to a satellite dish. If there’d been a good junk artist like Spencer in the multitude when Jesus said you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, he would have asked for clarification: how big was the ear, and how fancy a purse did Jesus have in mind?

Pipher and Spencer would get a pugnacious set to their jaw if you just mentioned ‘environmentalism,’ let alone called them ‘environmentalists.’ But they were of an American culture that practiced a lot more ‘deep recycling’ than those of us who accumulate virtue putting cans and bottles in the appropriate containers. They were of that Other America, that Counterrevolution still fending off the Industrial Revolution’s total conquest with a small mill here, a small farm there, committed to local production from local resources, and small enough in scale to be more or less sustainable, or know it if they weren’t.

“Learning to live with the Anthropocene’ being one of the alleged purposes of this patchwork of stories from the Colorado River Basin – I think the remaining pockets of the unrealized Counterrevolution might have at least as much to teach us now as the over-extended, over-built and over-heating Industrial Revolution does.

Pipher died last July at age 87, Spencer just a couple months ago at 91. The sawmill was sold to some nephews thirty-some years ago, and moved out of the Crystal Creek valley, down into the North Fork valley; I don’t know what has happened to it since. But I am thankful for my time with it, and for what it and Pipher and Spencer taught me about the America that might yet happen, in its own way, when the Industrial Revolution finally implodes and collapses on itself in a rich shower of junk – surely the junk artists will emerge when needed….

Next time: back to the larger Colorado River, and the beginning of the colossal encounter between the river and the Industrial Revolution….

I love this. I can see it – the glorious junk artists and hippies communing.

‘Communing’ is one way of putting it….

My Dad wanted me to be an engineer…one who would graduate from a very respectable school. Failing that, to follow in the family tradition of military service. Reckon I failed at both, but as a good blacksmithing friend once asked, ‘What is the difference between a mechanical engineer and a blacksmith?’ He didn’t know and neither do I. All junk artists are akin to the traditional blacksmith. Our scrap piles are our college tuition.

For many years I’ve known that l shared a similar Counterculture sawmill experience with George, but it’s touching and nostalgic to read it described so well in his prose. Mine was as a sawyer in a two-man mill in Tin Cup, Gunnison County, built and operated, until I showed up in ’76, by Bill Dugan, a transplant to Tin Cup from north-central Kansas. He too was a Pipher/Spencer kind of guy, not quite the junk artist but a master at bringing out the remaining life in any piece of old machinery suited for his purpose. After I arrived, Bill added a used (of course) 16′ Newman 500, five head planer to keep us busy transforming air-dried rough-cut boards into finished lumber and house logs on winter days too harsh to operate the sawmill. Thanks George, your piece is a wonderful walk down memory lane for me.

Great piece George! It was fun hearing an extension of the Luce Pipher story that seems to always be close to the tip of your tongue or fingertips. I have a scant memory of the man myself and it is a memory that puts a face on the type of people I grew up admiring as a child coming up in the 4 Corners area. The thing I learned most from those old ranchers and farmers is that you never throw anything away for it is an essential part of something you are going to create some day. And my own work as an artist reflects this mindset. Even when I was a door installer extraordinaire in Southern California I salvaged everything possible from old doors I was replacing. I still have some prime Mahogany and Oak that came from doors I took down to replace with newer ones. I have built many things over the years from “re-purposed” parts, and it has always been in recognition of my roots that were the same roots that Luce Pipher drew from.

I love your story telling as always and this piece truly engaged me at a deep personal level. Thanks.

Denny

I love the last line. Great piece . Don’t always just recycle, REUSE!

George, a good story of your journey thru the years

I knew Ken Spencer several years ago. I thought of him with the descriptive but hackneyed phrase, “gentle giant”. He was quiet, but always attentive. He also had the biggest hands I’d ever seen. I asked him one time if he could fix a cross member on my truck and he could and did. As is expected, I offered to pay him and as was expected, he refused—part of the culture of rural America. It was a good weld too. When his wife Donna died, he refused to eat anymore. Strong as he was it took a month for him to die. He came from a town in California that disappeared under a reservoir and how he got to Crawford I never found out, or maybe I can’t remember. We left Crawford almost ten years ago and I didn’t keep in touch, but of all the people I met there during our dozen years there, he remains among the most memorable and certainly in a good way.

Wonderful account of junk, two very admirable Crystal Creek ancestors, and a great meditation on the Agrarian CounterRevolution, as George likes to call it.