The third and final human invasion of the Colorado River region in the Holocene came from the east, from England and Europe and their Atlantic Coast colonies. The native peoples of the first invasion (10-11 thousand years ago from Asia via that Bering land-bridge) had risen up against the Spaniards of the second invasion, from Europe 500 years ago, and kicked them out in 1821 (Christian calendar).

But that same year, the cultural compass in the Hispano-Mexican El Norte began to shift toward the east with William Bucknell’s mapping of the Santa Fe Trail from Kansas City. In 1846, the Euro-Americans picked a fight with Mexico that they won in 1848, which gave them all the Hispano-Mexican lands north of the Rio Grande and Gila Rivers, including all but the last 100 miles of the Colorado River Basin.

The Santa Fe Trail and Gila River became a southern route to the California gold fields after 1848, with a community growing up around the ubiquitous fort and a ferry at Yuma in the 1850s. Prospectors and farmers worked their way up the lower Colorado River from Yuma to the lower canyon region no significant mining strikes were made, but some small farm settlements were made using the erratic river.

But the major Euro-American invasion into the Colorado Basin came via the headwaters, beginning with an 1859 gold strike in the Clear Creek canyon west of present-day Denver. This brought so many prospectors and miners so quickly that by that winter the surge had already breached the Continental Divide and was into the Colorado Basin; the Breckenridge post office in the Blue River valley west of the Divide was certified in 1860 at the same time as the Denver post office.

Until roughly the late 1950s, American historians viewed this westward invasion of Euro-Americans mostly in positive, even triumphalist, terms: a creative and energetic people sweeping over a mostly empty continent in a ‘westward expansion’ that filled the land with a bustling, wealth-generating civilization. This Frederick Jackson Turner-Ray Allen Billington school of American history (kept on life-support now by writers like David McCullough) was basically the mythos of ‘The Ascent of Humankind’ referenced here before, made specific to the Anglo-American invasion. Any collateral damage to native peoples already on the land usually resulted from their stubborn refusal to embrace a superior culture.

But then in the 1960s, the study of history, along with a lot of other things, underwent a sea change; ‘New West’ historians’ like Richard White, Patricia Limerick and Donald Worster countered that ‘good guys’ story with convincing narratives of the western movement as an ongoing ‘legacy of conquest’ by white Euro-Americans overrunning existing cultures, and imposing on them and the landscape alien concepts of property, profit and progress that the West’s rigorous and unforgiving environments continue to test severely – essentially, an ongoing ‘unsettlement,’ as Wendell Berry put it, that, at best, does not leave us looking like good guys.

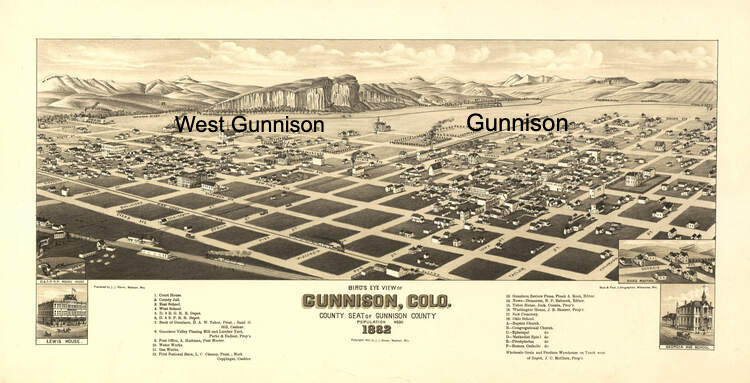

My problem with both stories is that neither tells me why, when the gold-silver fever reached my Upper Gunnison River home valley in the late 1870s, two distinct Gunnison towns came into being – literally side by side, coexisting, but with a distinct cultural separation for most of Gunnison’s first decade.

The ‘first Gunnison’ was not even part of the gold-silver boom running roughshod over the mountains; it was created by a much smaller, quieter and less ostentatious ‘colony’ of would-be farmers, modeled on the Union Colony that was then developing an ‘agri-culture’ in the vicinity of present-day Greeley, Colorado. Such settlements – ready-made communities – were a fairly common, if not dominant part of the Euro-American westward movement, going back to the Amish settlements in the mid-Atlantic colonies. Many of them were religious organizations.

The small Gunnison colony arrived in 1874, laid out a town plat, and its members also staked out agricultural claims bordering on the town. They declared their town to be alcohol-free – probably their main distinction from the mining camps which more or less ran on alcohol. The organizer of the colony was a jack-of-all-trades from the Denver area, Sylvester Richardson.

Through the late 1870s, gold and silver mining camps began to grow in the Elk Mountains, the San Juans, and along the Continental Divide, but the more philosophical and idealistic Gunnison, under Richardson’s leadership, barely survived, with members coming and going. Richardson acquired a water-powered sawmill which was located in Mill Creek (whence the name), and began developing an exposed coal seam in the Ohio Creek valley. But the colony itself barely survived as the realities of creating an agrarian paradise in such a rigorous environment sank in and people drifted away – or went to prospecting upvalley.

Then in 1880, the Leadville boom finally spilled over into the Upper Gunnison, and suddenly the Richardson company had a market for its platted Main Street – all of the mercantilists and saloonkeepers and madams and assayers and others who fed off of the hordes of prospectors who came to get rich, or at least get drunk and maybe laid. Richardson, who needed some money to develop his company’s vision, sold off Main Street to these invaders without any apparent qualms – then moved his company and their vision five blocks west in the plat to ‘Boulevard Street.’

So there they grew, side by side: the wide-open mining boom town of Gunnison, and the much more sedate and settled agricultural town of West Gunnison. Gunnison had all the basic trappings of the urban world, including a shop for fine cigars and wines, and dry goods stores advertising ‘the latest Paris Fashions.’ West Gunnison, on the other hand, had a school, a couple churches, a literary society, and a family orientation, and served the farmers and ranchers beginning to fill in the valleys radiating out from the ‘hub’ of the two Gunnisons.

The difference between the two towns was best articulated through their newspapers. Gunnison after a couple years had four weekly newspapers that eventually consolidated into two dailies – this for a town with a few hundred ‘permanent’ residents. But these papers were not meant to inform the local populace; they were to go out to the larger world, to boast about a town whose amazing future was still materializing. The Gunnison Democrat promised ‘in local and home matters to be reasonably honest.’ This included allowing mine promoters to give their own ‘reports’ on whatever coming gloryhole they were developing that week. ‘Reasonably honest’ was a fungible term.

That kind of boosterism irritated Sylvester Richardson enough so that in 1883 he came out with a West Gunnison newspaper, The Sun, promising in its masthead to be ‘independent in all things, neutral in none.’ Instead of mine promotions, he devoted a locally written page to ‘Popular Science and Agriculture.’ He published the otherwise lost works of the West Gunnison Literary Society. And he wrote editorials, unappreciated in the other Gunnison, on topics like why were liquor licenses so cheap when the city had to lay out thousands of dollars to deal with the legal and criminal consequences of liquor in the community.

For the first half of the 1880s, with prospectors and miners flooding into the mining district, this looked like an overmatch that the Richardson company couldn’t survive. But as was usually the case, the mine boom cooled fairly quickly in the late 1880s, and after the Sherman Silver Act in 1893, it went into its death throes. Meanwhile the ranchers around the two Gunnisons continued to plug along, and by the dawn of the 20th century the two Gunnisons had blended into one primarily agricultural town – except that the railroad was still there, hauling coal and coke from the more industrialized Crested Butte to the Pueblo steel mill, and eventually livestock from the ranches too.

So what was really going on here? I submit that this was just an unusually close encounter in another story explicating the Euro-American westward expansion. The story began back in England and northern Europe, and was, again, basically a story about population pressure – what to do with too many people. As was the case in most of the previous Holocene population expansions, the excess people under the English and European feudal subsistence agrarian culture gathered in urban enclaves where alpha elites emerged to organize them in division-of-labor systems for basic infrastructure work and the manufacture and trade of value-added goods.

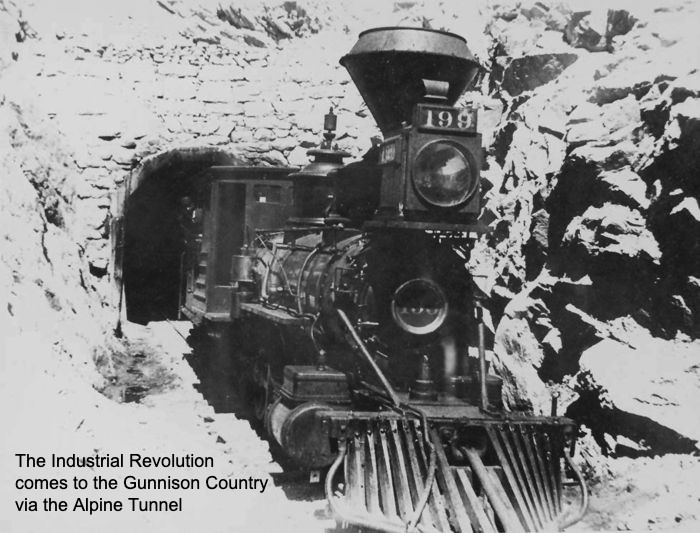

But two unique changes made this industrialization process different from most of those of the past. One was an initially reluctant move into the fossil fuels, compelled by a shortage of the historical fuel of choice, wood. The use of coal in England and Europe took hold, however, and fired up the Industrial Revolution, especially after the advent of the steam engine in the mid-18th century.

The other change was the ‘discovery’ of the vast new continent out in the western ocean – a continent rich in all the raw resources needed for civilized life, and occupied only by peoples still stuck in the Stone Age – people who would undoubtedly be astounded and delighted to see and partake of the blessings of civilization….

This brave new world beckoned strongly to two classes of Anglo-Europeans. One was those connected enough to have financial backing from English and European private capitalists, or a charter from a king (i.e., Massachusetts Bay Colony), or both – go-getters who saw the new continent as a boundless source of raw resources to feed the burgeoning Anglo-European Industrial Revolution.

The other class was those less materially blessed, many of whom had been evicted from ancestral feudal farm lands enclosed and privatized by the aristocrats providing wool and other raw resources for the Industrial Revolution. The dispossessed farmers saw going to America, with the rumors of unlimited free land, as a very desirable if difficult alternative to going to England’s and Europe’s foul industrial cities, or worse, to the coal mines that fueled the cities. Many of them sold themselves into indentured servitude to get to America.

That was the origin of what I want to call ‘two Americas’: a moneyed class advancing the explosively expanding Industrial Revolution, and a less wealthy class trying to escape the Industrial Revolution and return to agriculture – an Agrarian Counterrevolution. And the vast continent westward (beginning on the Atlantic coast) became their proving ground, and occasionally, battleground.

Early on, it seemed there might be room for both on the vast new land. Westward lay what Thomas Jefferson, chief cheerleader for the Agrarian Counterrevolution, described as ‘an immensity of land’ to be settled by the ‘yeoman’ farmers that populated at least his imagination, a repository of ‘substantial and genuine virtue’ who would create a decentralized agrarian republic with political and economic power down on the ground with the people.

‘While we have land to labour,’ Jefferson concluded, ‘let us never wish to see our citizens occupied at a work-bench.’ To the dreamer, the idealist, America did look like going back to the beginning, a chance to start over and do it right.

But the yeomen also needed some material goods from those industrial workbenches – the village smithy couldn’t do it all – and some cash for land fees and taxes, and so had to raise enough produce to sell surpluses to the city for shillings in order to buy value-added goods for which they paid in pounds; prices and payments both ways were set by the city. The farmers began to feel oppressed by the cities that seemed to control the New World’s economic life, as they had in the Old World.

Meanwhile, the avatars of the Industrial Revolution in the cities were hobbled by England’s mercantile refusal to export its industrial technology; the homeland just wanted raw resources from the colonies, with the value-added manufacturing kept at home. So the would-be industrialists on the coast began to feel oppressed under British colonial rule.

That led to the so-called American Revolution, in which the inland farmers oppressed by the city economy (i.e., the Green Mountain Boys), and the city businessmen oppressed by mercantile policies (i.e., the Sam Adamses) united to drive the British and their Old World political economy out of the New World.

But the tenuous nature of that alliance was revealed after the British took their army home; the Americans continued the fight among themselves. Shay’s Rebellion in Massachusetts was waged against the coastal bankers, and had at least verbal support from farmers throughout the colonies – as did the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania a little later, an uprising against a tax on whiskey that favored large urban producers over the little farmers trying to get their surplus grain to market in the most compact way.

So what was emerging in the Not Entirely United States after the British abandoned the ‘colonies’ was an internal tension and contention between the Industrial Revolution and an Agrarian Counterrevolution. The impetus obviously lay strongly with the well-funded Industrial Revolution, an ‘idea whose time had come,’ as Victor Hugo put it. The Agrarian Counterrevolution, on the other hand, was partly nostalgia for a way of life lost to the usual population pressures, and, like all more romantic movements, was never very well articulated and defined – but was, like all romantic movements, passionately felt and advocated.

This civil contention was also influenced by a new indulgence created by the Enlightenment: the self-conscious individual who, working in his own best interest (according to Adam Smith), would also be working in the interest of all. That kind of individualism favored the movers and shakers of the Industrial Revolution out to enrich themselves which supposedly created wealth for the larger community; but it did not work that well for the Agrarian Counterrevolution and Jefferson’s rugged yeoman farmers who went out into the wild to carve out farms, a life and, Jefferson hoped, a grassroots decentralized democratic governance. This worked best when a colony of farmers went out together to carve out a farm community (especially if some of them were actually farmers). Religious colonies seemed to succeed best. But two out of three homesteads created under the various laws permitting ‘appropriation from the commons’ eventually failed, most due to inexperienced individual families trying to do it alone.

The opening of the lush Old Northwest Territory, and then Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, seemed to give an edge to the Counterrevolutionaries who had come to America to escape the Industrial Revolution – that immensity of “land to labour.” But by then the Industrial Revolution – Alexander Hamilton’s America – was literally picking up steam, in the form of the railroad, and the Agrarian Counterrevolution became a long westward retreat, trying to stay out of the Revolution’s expanding webs of transportation and finance.

The industrialists had reason to tolerate, even encourage to a point, the agrarians. The Counterrevolution served as a kind of safety valve against the generally mean working conditions and pay under the Industrial Revolution; malcontents who might otherwise become union organizers could be encouraged, or warned, to ‘go west, young man.’ And since two out of three failed in their agrarian homesteading, they became a western labor supply for industry.

The industrialists, however, did need to get the agrarians on board with ‘industrial production’ to feed their cities. They didn’t want agrarians growing diverse crops to supply their local communities; they needed farmers to grow big monocultures of commodities – wheat, corn, beef, pork – to be transported to centers like Chicago and Kansas City for processing and further distribution to the industrial cities.

They managed this ‘capture’ through interwoven networks of finance, transportation and communication – all industrially created and controlled: easy credit for farmers and ranchers (which, given the vagaries of nature and personal disease and disaster, most eventually needed), and commodity prices and shipping rates pitched to keep the farmers from getting far enough ahead to not need the binding credit. The farmers were always selling their production into a buyer’s market, and buying what they needed from a seller’s market. William Cronon has laid out this process in Nature’s Metropolis, his study of Chicago and the creation of the commodities markets.

It became cultural custom, down to the present, to pay official lip service to ‘family farms,’ while the Industrial Revolution continued to overrun and co-opt them. Abuses by the ‘cutting edge’ tools of the Industrial Revolution – the railroads, commodities markets, central bank financiers, and the catalog companies – gave rise to more serious conflicts between the two Americas, as articulated by the grangers and small-p populists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: farmers revolting politically against the industrial networks subtly forcing Jeffersonian agriculture into industrial agribusiness. Some of the revolt was peaceful, as in the formation of marketing co-ops; some turned violent through sabotage, but ultimately the Industrial Revolution always prevailed.

Today the triumph of the Industrial Revolution seems to be almost complete, there being virtually no place where the urban-industrial web is not laid over the rural landscapes, from the increasingly consolidated farmland, confined animal farms and processing factories in the plains, to the headwaters resort towns in the mountains with their ‘recreation industries,’and all economic roads leading to the industrial megalopolises.

Yet people still come to places like these headwaters looking for some other America. Myself included, coming 50-some years ago to an end-of-the-road town on the edge of apparent wilderness, where I could briefly believe I had escaped the Industrial Revolution – until I went to work in the recreation industry, which with its ancillary real estate and construction industries is gradually consuming what was left after the mining industries finished. The old-timers left behind by the mining industry liked to say, ‘You can’t eat scenery.’ But you can, and then that’s gone too.

Surely we could do better, or at least different, out here in the hinterland that was supposed to be the other America. Especially with the triumphant Industrial Revolution starting to show its age, and an inability to deal with its own consequences. And there are small beginnings – the local food movements popping up, ‘slow money’ becoming available, more looking to the sun and wind rather than the pipelines from ‘out there’ for energy. But it is as hard to imagine living without the Industrial Revolution as it’s been to live with it – and I don’t really want to choose, can’t. It’s still our destiny to figure out where, between our consummated revolution and the still unarticulated counterrevolution, our undisciplined creative brain and our wild romantic heart, lies the America where we are neither this nor that but the best of both….

Next time – unleashing the Industrial Revolution on the Colorado River, two irresistible forces….

This is getting better with every chapter

Interesting history lessons as always – glad you ended on a hopeful note and hoping you are right – that we will find a way to survive with the best of both worlds.

“Neither this nor that but the best of both” is vintage Sibley—positive attitude and hopeful outlook. And were we to leave the future up to the Sibley’s, “positive” and “hopeful” would be rigorous rallying cries.

On another point: this is awfully long and takes dedication, even out and out adoration, to read all in one sitting. But to NOT read it in one pass is to reduce its power. I am positive and hopeful we can all figure it out.

To sum up, those revolutions and now this one are together proving to be the end of us.

I apologize for the length. I try to keep them in the 1,500-2,000 word range, but this one ran away with me….