Recent posts here have mostly been about the Colorado River – its chaotic origins, the source of its waters, and the things that happen to its waters immediately after falling onto the Southern Rockies, the geology it has carved, the biota it has nurtured.

It should be no surprise, given that geography of climatic and geological circumstances, that the river has a very erratic water supply; with its headwaters nearly a thousand miles from the ocean, big north-south mountain ranges taking most of the water en route from the ocean, and big subtropical high pressure ridges of dry air in free fall stalking the whole region, it is almost miraculous that any water makes it here at all.

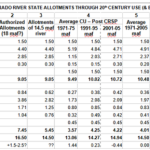

Looking at historical numbers, the river’s annual flow has averaged around 14.8 million acre-feet (maf) through the 20th century – a quantity that the Mississippi River pours into the Gulf of Mexico every few days. But even that average is deceptive; the annual flow has ranged within a single decade from as little as 5.8 maf (1977) to as much as 24.5 maf (1984). (An acre-foot is ~326,000 gallons, water enough to cover a football field a foot deep.)

The average since 2000, however, has been less than 13 maf, due to a two-decade ‘drought’ I’m sure everyone has heard about. Climate scientists say this drought is probably about half ‘natural climate variation,’ and half ‘Anthropocene’ – a permanent aridification due to increased sublimation, evaporation and plant transpiration caused by rising ambient temperatures. Temperatures that are going to keep rising through at least mid-century, with rises beyond that dependent on how successful we are at reducing the greenhouse gases we keep pumping into the atmosphere.

A 2022 study says that this is the worst extended drought the West has experienced in 1,200 years, which takes us back via tree rings to prehistoric times in the Colorado River Basin; Western Civilization did not arrive in or around the Basin until about 500 years ago, when Spanish conquistadores began to foray up from Mexico.

There were, however, humans living throughout the region of the river 1,200 years ago – around 800 CE (Christian Era). They were then – most of them – working through one of the big steps in the ‘Ascent of Humankind’ story we like to tell about us humans – remember that story, from an earlier post? Our ascent from raggedyass nomadic hunter-foragers, to settled farmers producing surpluses, and on to interconnected civilizations with highly organized societies and highly developed cultures, like our own Western Civilization?

The people in the Colorado River Basin 1,200 years ago were in various stages of the transition from the subsistence hunter-forager culture to agriculture. We tend to regard this as a great step forward for humankind – but there are dissenting ideas about that. Yuval Harari, in his fascinating ‘Brief History of Humankind,’ Sapiens, called the Agricultural Revolution ‘history’s greatest fraud,’ a terrible deal for humans. Hunter-foragers generally met their needs with five or six hours of work a day, while farmers labor dusk to dawn and generally have a less varied and interesting life than their nomadic brethern had.

While Harari probably exaggerated the pleasures of hunter-gatherer subsistence, he does raise an interesting question: why would any human group voluntarily give up the comparative freedom of the hunter-gatherer way of life for the heavy work of rearranging nature to concentrate plants for agriculture? I can only think of one reason: like Adam and Eve, they didn’t leave their Original Garden voluntarily….

But that leads us into another story – a darker story than ‘The Ascent of Humankind,’ a story I will call ‘The Traumas of Success.’ A story that begins with a changing climate. Around 12,000 years ago, the planet wobbled into a new angle with the sun, and the cold dry epoch of the Pleistocene slipped into one of its ‘interstadials’: comparatively short periods of global warming. The vast ice sheets and mountain-burying glaciers melted back; plant and animal life surged to reclaim the ‘landscrape’ abandoned by the ice as the world warmed.

This included humans, who had crossed from Asia on the Bering land-bridge exposed by lowered Pleistocene oceans. By the time the Big Ice began to melt, people had spread out into practically every area not covered by ice – small clan-based bands staking out the large territories that hunter-foragers need. They inhabited the Great Basin from the Columbia Plateau to the Colorado Plateau, from the Sierras to the Rockies, and on down through the Colorado River Basin to its subtropical deserts, and into what’s now central Mexico. Archaeologists call these dispersed bands of hunter-foragers the Paleoarchaics.

They even came to the Upper Gunnison, once they could get here, probably through the Cochetopa Hills, between 10,000 and 11,000 years ago. They, along with dire wolves and sabertooth cats, were following the big game – really big game, giant buffalo, musk ox, mammoths. They, like Paleoindians everywhere on the continent became specialists at killing the big game, with nothing but collaborative strategies and spears tipped with beautifully executed long stone points.

This big-game hunt became their identity, and they got so good at it that, within a few thousand years, they experienced their first trauma of success: the big game disappeared. The warming may have had something to do with that with the wooly Pleistocene creatures, but driving whole herds over ‘buffalo jumps’ has to have been a factor.

The Paleoindians who had hunted the big animals began to hunt what was left – deer and elk, the smaller buffalo, beavers, fish, snakes and frogs, anything that moved, and they depended more heavily on the foraging side of their diets – pine nuts from the piñons, berries, various greens, roots and tubers. The evidence of their diets from their middens was so different from the large bonepiles of the Paleoindians that many archaeologist assumed the Archaics were a totally different people. It is more likely that they were the same people changing their diets to adapt to what was available, but the end of the Great Hunt must have been a serious blow to their sense of who they were. The trauma of success.

Meanwhile – the warming world, the mellow Holocene, was having other impacts on all the peoples of the interior West. Fewer children were dying in their early years; more people were living into their thirties, forties and beyond; the diseases that were exacerbated by the dry cold of the Pleistocene were losing their killing power. Populations were expanding, and as the populations expanded, the pressure on the lands they depended on increased; they all needed larger territories.

Around 3,000 years ago, after a 7,000-year run (we are working on 200 years here), the evidence of human inhabitants disappeared from the Upper Gunnison – about the same time that the piñon pines disappeared from the valley, a staple of their diet. Coincidence? Where the people went we don’t know, but it makes sense to assume that they went as a band in search of new territory. But it is probable that everywhere they went, they found people already there – most of them also experiencing population growth and the need to expand territories for their hunter-forager lifeways.

This was happening throughout the Southwest, and by 2,000 years ago – zero on the Christian calendar – the various peoples of the Colorado Plateau and throughout the Basin region began raiding and outright fighting over territory, chaotic conflicts that went on for around 900 years.

But also going on then (probably mostly with the women) was a transition to agriculture. The peoples had long known that edible plants grew from seeds, but now there was reason to use that knowledge to concentrate edible plants in defensible places. And people practicing agriculture could comfortably live more densely; they began to settle into more defensible villages.

Did they miss the old free-ranging life? Probably. It’s important to remember that this transition came slowly over a millennium – hunters probably kept hunting as long as there was fauna to hunt; but ultimately, in this story we’re in now, they faced a Hobson’s choice: either change their lives and become toilers in the soil, or endure endless fighting over too little territory. Either way, the ‘good old days’ of the Paleoarchaic period were gone. We had become a swarming species. But rather than submitting to the die-off that nature imposes on species that swarm, we were clever enough to change ourselves to fit the new condition – at the price of the lifeways we had known forever. The trauma of success.

One of the advantages of the agricultural way of life was the production of food surpluses – and since the rainfall in the high deserts of the Colorado Plateau region was erratic in both where it fell and when it fell (or didn’t), surpluses from one year to the next were often essential. The surpluses also afforded the opportunity to free some of the people up for other community tasks – artisans to make pottery and other goods for both home use and trade with other villages.

But the surpluses also nurtured…population growth. We kept succeeding at keeping ever more people alive. Villages grew larger, and more villages came into being. Interactions among villages – both cooperative and competitive, friendly and antagonistic – became common; within a few centuries, we were once again experiencing the unorganized pressure of too many people.

Settlement became most concentrated in the San Juan basin, tributary of the Colorado River. That notable regional drought 1,200 years ago, around 800 CE, may have nudged the people in villages who survived it toward a more integrated culture that emerged among the villages in the Chaco Canyon area, binding them together with what seemed to be a centralized surplus storage system for the growing basin villages.

As best as can be determined from the mute archaeological evidence, infused with archaeological imagination, the basic concept seemed to be to share as broadly as possible the risk of bad growing seasons. The summer rains they depended on did not fall evenly everywhere; some villages would get good rains while others were dry, but that luck tended to move randomly around the region. There were also episodic droughts lasting several years. With storage of surpluses centralized in several larger communities, there would be surpluses coming in from villages blessed with good rain in any given year to redistribute to villages less blessed. How the redistribution was managed is unknown – a ‘love thy neighbor’ religion? A market economy (trading increasingly beautiful pottery for food)? An enforced communism?

What is known, from the mute remnants, is that the Chaco Canyon ‘Interconnect,’ as it is sometimes called, got big. Multi-story masonry buildings for both storage and living were built from around 900 CE to 1150 in several centers in the San Juan Basin, all connected by broad straight ‘highways,’ even though the people had no wheeled vehicles. The building process culminated in the massive Pueblo Bonito – the largest building in North America until surpassed by urban structures in American cities in the mid-19th century. The buildings and roads alone required new kinds of socioeconomic organization. Timbers for multi-story buildings had to be hauled from the mountains with manpower, since the people had neither domesticated animals nor wheeled vehicles; building masonry structures several stories high requires some specialized workers.

Some of these ‘industrial workers’ may have been farmers from the villages employed in winter work. But over the visible labor there was a hierarchy of more sophisticated tasks – organizing and running either the religious economy or the economic religion, determining what surplus each village owed to the system and arranging for its collection, keeping track of the collection and redistribution of stored surpluses, and other tasks associated with an increasingly complex and extended system. This upper hierarchy required ‘elites’ that one would not expect to automatically arise from bands of former hunter-foragers become farmers, but probably every group has its creative alpha Cain for every dozen dependable beta Abels.

For a century and a half, it worked – 1000-1150 CE, a time of peace and relative prosperity. Then, in the fifty years following the peak of construction around 1150 CE, things just began to fall apart. A nasty spell of drought undoubtedly contributed to it, but nothing so bad as the 800 CE drought. Nonetheless, over the next century the complex Chaco Interconnect became thoroughly disconnected; by 1250 its villages or groups of villages were at violent war with each other. Those villagers who were not already living in cliff dwellings created new ones for defense, not against marauding outsiders but against their own former neighbors. Starvation was rampant.

Why do civilizations like this, so highly organized, always seem to fall apart? A similar thing was happening farther south in the Colorado River Basin, in the Salt River tributary, where an irrigation civilization emerged similar to those of the Fertile Crescent in Asia Minor, at about the same time that the ‘Ancestral Puebloans’ were creating their integrated civilization up in the San Juan River basin. Both of those civilizations fell apart at roughly the same time. Archaeologists posit lists of reasons, but all of them include population increase; many note that the complexity of civilization may be just too much for the evolved level of our brains.

What happened to the people? Most of those who survived the warfare and starvation simply walked away from the whole thing, and relocated – some southward to northern New Mexico and northeastern Arizona, where they ‘downshifted’ back to an agrarian village society; others eastward into the Ro Grande Basin where they also ingratiated themselves into decentralized agrarian cultures already there.

And some, no lovers of the farming life, headed north into the mountains where they downshifted all the way back to the hunter-forager life. Some anthropologists believe that the Ute people might have originated that way – the people who, after a 4,000 year absence, returned to the Upper Gunnison headwaters, if only for the summer and fall. They all claimed the Ancestral Puebloans as ancestors.

So what is this new story that I propose as an alternative to the ‘Ascent of Humankind’? A mythic story probably too humbling and depressing for most of us to appreciate: a climate-driven story about the traumas that accumulate around a species so successful that it goes out of balance with its ecosystems. Blessed by the mellow Holocene climate, we have consistently followed too enthusiastically the biblical mandate to ‘go forth and multiply.’ But then, rather than accepting nature’s die-off that would bring us back in balance, we have rearranged, recreated those ecosystems to support us in new cultural configurations, at considerable cost to other species in the old ecosystems – and then we’ve proceeded to outgrow those reconfigurations, requiring further adaptation of the planet to fit us. In this sense, the Anthropocene is not new; it has just finally become unignorable.

For the peoples here before us in the Colorado River region – our ancestors too – all of this happened in less than ten thousand years, for a species with a brain and soul evolved over a million years of wandering hapless and free under the sun and stars in the vast spaces of the planet. One doesn’t know whether to fear or hope that something of that older soul is still in us, but balanced by an awareness of the traumas of success, as we proceed to write the next chapters of the Anthropocene story.

Next time: on to the American Revolution – and Counterrevolution….