Breaking news! The Lower Colorado River Basin is threatening the Upper Basin with a ‘Compact Call’ if it does not agree to share some major cuts in river use! Well, actually the news broke a week ago – and now there’s more news: just as I was wrapping this analysis of the ‘Call’ up yesterday, the Bureau put out for our consideration five options for river management up to and beyond the 2026 termination of the ‘Interim Guidelines.’

So we’ll interrupt our out-of-the-box exploration for management options for living with a desert river in an intelligent universe, and try to figure out what’s going on back in the surreal world of the ‘Compact box’ – looking at the ‘Call’ situation here, then get into the five management options in a couple weeks after the dust has settled.

The Lower Colorado River Basin has attempted to break the stalemate between the two Compact-designated Colorado River Basins, by telling the Upper Basin that, if they do not agree to share some major cuts when the river situation grows desperate again, then in that desperate time they will issue a ‘Compact call’ on the Upper Basin to deliver the whole 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) on average they claim the Compact obligates the Upper Basin to deliver regardless of the water situation upriver.

There has been no formal Upper Basin Commission response to that threat, but Colorado’s Commissioner, and director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, Becky Mitchell, essentially called the bluff, and put the blame for Lower Basin problems back on the Lower Basin. The Upper Basin has argued that, if the situation becomes so desperate that the Lower Basin’ share cannot be delivered without draining Powell Reservoir, then the Upper Basin users will already be experiencing extreme shortages levied by nature.

This Hobson’s choice from the Lower Basin hinges on Article III(d) of the Colorado River Compact, which says, ‘The States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.’ Does this mean, as Lower Basin states will argue, that the Upper Basin has a ‘delivery obligation’ of 75 maf over any ten-year period, regardless what is happening weatherwise in the Upper Basin? Or does it mean, as Upper Basin states are likely to argue, should argue, that if the flow to the Lower Basin were to fall below that 75 maf over a ten-year period due to circumstances other than human uses in the Upper Basin states (drought, dead pool in Powell Reservoir due to excessive releases, the atmosphere’s growing ‘evaporative demand,’ et cetera), causing ‘the flow to be depleted’ below the 75 maf minimum, then responsibility for the depletion does not fall on the water users in the Upper Basin, but on changing natural processes beyond human control. The Upper Basin could, maybe should, argue that this condition in the Compact is simply a reminder to Upper Basin users, to be careful in using their 7.5 maf half of the river (cue bitter laughter), to not infringe on the Lower Basin’s 7.5 maf half of the river.

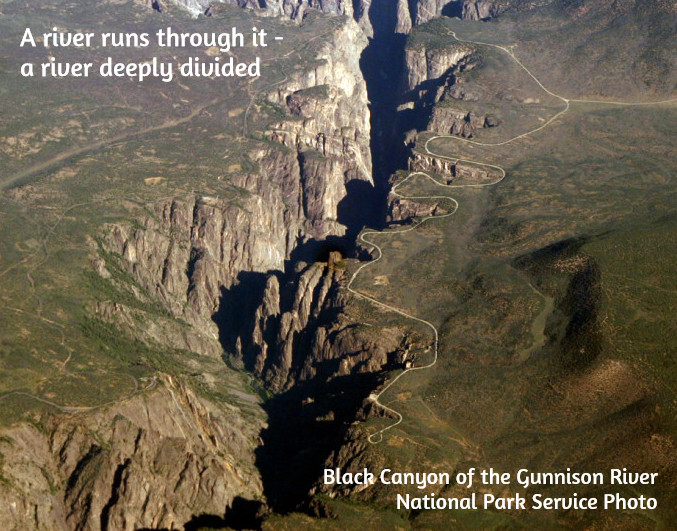

And so far as the Compact goes, that reminder is all there is. Nowhere in the Compact is there any provision for a ‘Compact call,’ or any other procedure when or if the flow at Lee Ferry (the ‘Mason-Dixon line’ between the two Basins) were to fall below that 75 maf over ten years. A ‘call,’ the reader might remember, is an unneighborly procedure in the appropriations doctrine that remains the foundation of water law in all seven Colorado River Basin states: if downstream water users with senior rights are not able to get all of their appropriated water, they can place a ‘call’ on upstream users with junior rights, who have a legal obligation to let enough water go past their headgates to fill the seniors’ rights.

The explicit purpose of the Compact, in fact, was to preclude states placing calls on each other; as the preamble to the Compact says; commissioners from the seven states gathered in 1922 ‘to provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System … to promote interstate comity (and) to remove causes of present and future controversies.’ In other words, they wanted to divide the use of the river’s water equitably among the seven states, rather than getting into a seven-state horserace for appropriations, with California already at the first turn while the other six states were still trying to get out of the starting gate. And the only way they saw to do that was to create a legal framework that would preempt the appropriations doctrine at the interstate level, and provide each state with a set share of the river to develop in their own good time.

A seven-way division of the use of the river, however, proved to be nearly impossible. Each commissioner had come with the charge to protect their own state’s glorious future, to develop their vast acreage of potentially irrigable land, their mineral resources, et cetera. No factual studies existed to support the glorious visions. And when the water requirements for those visions were all added up, they would have required a river half again larger than even the overly optimistic flow numbers provided by the Bureau of Reclamation.

The Bureau hovered around the Compact meetings, eager to ‘make concrete’ the final purpose stated in that Compact preamble: ‘to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property from floods.’ The Bureau wanted to build big dams on the Colorado River, and ‘expeditious agricultural and industrial development’ was the rational cloak the Bureau and the commissioners could throw on over the romantic urge to just take on the conquest of Fred Dellenbaugh’s ‘veritable dragon’ of a river.

Herbert Hoover, U.S. Secretary of Commerce and chair of the Compact Commission, and an engineer by training and romantic inclination, also wanted to build big dams. And when the commissioners grew frustrated at their failure to resolve an equitable seven-way split of the use of the river after several days of looking at magical numbers, he worked hard to keep them from just dropping the whole idea, reminding them that Congress would not approve funding for Colorado River projects until the seven states all felt satisfied that a share of the river would be there for them when they were ready to grow like California.

Still, he was unable to pull them together for a serious working meeting until November, nearly the end of the year they had given themselves to create their interstate compact. He was able to lure them with an idea he and Delph Carpenter, Colorado’s commissioner, had cooked up over the summer: instead of the currently impossible seven-way division based on vague visions, they would work out a two-way division, dividing the river into two Basins, the four tributary states mostly above the river’s canyon region as an Upper Basin, and the three states mostly below the canyons as a Lower Basin, and each Basin could have the use of half the river, to divide further among each Basin’s states at their leisure.

Holed up at the posh Bishops’ Lodge just north of Santa Fe, with 28 formal meetings in 11 days and who knows how many off-the-record breakfast and bar caucuses and drafting sessions, they came up with a Compact that no one loved, but six of the seven thought they could live with, to satisfy Congress that they were all on the same page.

The seventh state was Arizona. Arizona’s commissioner, W.S. Norviel saw from the start that this two-basin idea caged the thousand-pound gorilla, California, to the satisfaction of the four Upper States, but left his state in the cage with the gorilla. He signed off on the Compact – possibly so Hoover would let them go home – but his state legislature refused to ratify the Compact. And all the other six states only ratified it after months of persuasion that it was as good as they were going to get.

Congress, on the other hand, was sufficiently infected with the romance of conquest to be willing to ratify the Compact with only six of the seven states on board. The next step was the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1928, clearing the way for the construction, begun under President Hoover, of Hoover Dam, Parker Dam, the Imperial Weir Dam and the All-American Canal – a massive project that was about the only thing happening in America in the Great Depression, and which was adopted by the Roosevelt administration as the model for the Public Works Program and several other New Deal programs to put America back to work on big visions.

But at the base of all that is the rushed and rickety Colorado River Compact, the ricketiness of which was acknowledged by most of the commissioners – and by Hoover himself, who in one of the later November compact meetings, summarized the emerging compact as ‘a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river.’ (Italics added) If the legal and political infrastructure isn’t quite in place – never mind: go ahead and build the physical structure anyway.

We have the whole chain of laws, subsequent compacts, court decisions, interim guidelines and other fixes that have tried to shore up the Compact – the Law of the River – but nothing that really addresses the matter of the 7.5 maf promise to both basins that the river cannot support – and that the Lower Basin now seems to be considering, on the basis of that Article III(d) obfuscation, as an appropriated right that the gives them a kind of seniority over the Upper Basin.

Isn’t that what this ‘Compact Call’ threat is? Hasn’t the Lower Basin essentially tried to graft the Compact onto the appropriations doctrine in order to threaten the Upper Basin with a ‘Compact call,’ despite the expressed intent of the Compact to create an equitable division that would preclude post-Compact appropriation calls between states?

I’ll leave it there, hoping that someone with a greater fund of information can explain this to me. Watch the ‘Comments’ section here.

And then we’ll dig into the Bureau’s recommendations in a week or two. And forget, for the time being, trying to think outside the Compact box; it demands our attention, love it or not.

As always, a thoughtful analysis of the results of maneuvering around the impossible in a world structured around the immovable. Anxious to read the next prognostication!

Thinking the the Colorado River Water Users Association next week might be more interesting than usual. As usual California is the bully who cannot control its own water use. Not all the Upper Basin is blameless but several states have made some significant reductions in careless water use while California still fails to regulate most of groundwater mining. You’ve been at it a couple of years longer than me and I don’t know why you are not exhausted at how little things change and how much good advice over the lat 50 plus years has simply been swept aside. When it is my way or the highway there isn’t much hope.

Hmmm… and what if – in that hopefully hypothetical situation – the upper basin states refuse, Trump-like, to pay attention to “norms” and “accepted practice” by refusing to cooperate with the “Compact call?” I suspect that, by the time the ensuing litigation has run its course, Mr. Trump will be out of office, whether through a natural death or constitutional limitations that even MAGA Senators are not willing to ignore. What then?

Let me add, now that I’m no longer a resident of one of the upper basin states (unless you’re thinking of the “upper basin” of the Mississippi, which has its own issues), that the appropriations doctrine so widely, and apparently fondly, adopted in western states, has never made any sense at all to me in a context of the sort of “equity” that the language of the Compact seems to endorse. “Equity” and “I was here first, go away!” and/or “Equity” and “I’m bigger than you (economically, politically, etc.). Tough luck.” don’t strike me as attitudes that would allow the neighborhood kids to play well together. Just a thought from a Midwesterner…

And on it goes. Fascinating. Seems that some progress is being made. By slicing & dicing in every possible direction, some details seem clearer. And the more talk & meetings, the more everyone understands big pic. Blah blah no idea what I am talking about. Help, Gs

Happy t giving. I am going to Denver to be with la famille

Thanks and enjoy your Thanksgiving.

Pingback: Romancing the River: Bluffing a Call, Calling the Bluff — George Sibley (SibleysRivers.com) #ColoradoRiver #COriver #aridification – Coyote Gulch

Thank you George.

As you described, the Colorado River Compact was initially based on an equitable apportionment of consumptive uses but is now based on an unchanging delivery requirement. This delivery requirement is the foundational point for current Colorado River management. The proposed operations alternatives end up being built around this foundation rather than being built to optimize basin-wide objectives.

Given this fixed requirement and the threat of litigation if it goes unmet, and given the current hydrology, Upper Basin water managers would be irresponsible if they did not store as much water as they could in Upper Basin reservoirs and if they released more than the minimum necessary amount from Lake Powell.

In Reclamation’s recent three-page teaser on proposed operations alternatives, however, they note that some “would require additional federal authorities and stakeholder agreements.” Do you think this might mean that they would consider going outside-the-box created by this delivery requirement?