We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.

– Senior advisor to Pres. G. W. Bush, 2004

You’ve seen that quote here before – and you’ll probably see it again; if this were a Wagnerian opera, that line would be a lietmotif, a recurring musical thread associated with a particular character or place or idea in the story being told musically. And who’s to say, ‘The Romance of the Colorado River,’ Frederick Dellenbaugh’s title, might make a grand opera.

But before launching into the next chapter in the ‘Romance of the Colorado River,’ there are some items of news to note. The no-news item of course continues to be the ongoing stalemate in the ongoing negotiations between the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins. On the eve of their Valentine’s Day deadline, there is talk of new ‘interim interim guidelines,’ two to five years, for at least a nominal state presence as the Bureau of Reclamation tries to keep the lights on and some water flowing.

The bigger news is the extent to which the Colorado River Basin continues this winter to experience the reality we have created: an ongoing anthropogenic ‘heat drought’ (February temperatures in the 50s to 8,000 feet elevation this past week), coupled with a ‘dry drought’ – probably also caused by anthropogenic warming-induced changes over the Pacific Ocean. Snowpacks in the mountains from whence the river’s waters flow range from 35 to 85 percent of normal in mid-February; we may be heading for new records in low runoff.

The biggest news, but probably less noted, is a new take on the larger reality we have created globally. Late in January, the United Nations headquarters came out with a fairly astounding announcement:

‘Amid chronic groundwater depletion, water overallocation, land and soil degradation, deforestation, and pollution, all compounded by global heating, a UN report today declared the dawn of an era of global water bankruptcy, inviting world leaders to facilitate honest, science-based adaptation to a new reality.’ (Emphasis added)

This announcement was generally ignored, in the world’s morbid fascination over ‘what the Trumpsters are breaking today.’ But the scientists who generated this report claim that phrases like ‘water stress’ and ‘water crisis’ are too hopeful, suggesting deviations from a normalcy that we might somehow be able to get back to. Today, they say, ‘many rivers, lakes, aquifers, wetlands, and glaciers have been pushed beyond tipping points and cannot bounce back to past baselines.’ Bankruptcy.

A short list of global ‘hotspots’ included the American Southwest, where ‘the Colorado River and its reservoirs have become symbols of over-promised water,’ with no reasonable hope of ever fulfilling those promises. Nothing new there – but calling it a state of bankruptcy bumps the desperation level up a little.

I am not going to get deeper into that report today, or the other news, but will hold it for the last chapter (to date) in this unfolding ‘Romance of the Colorado River.’ If the report intrigues your morbid fascination with the apocalypse we seem to be driving toward, as the Trumpsters and financializers part out our civilization for distribution to the morbidly wealthy, you can find the report by clicking here.

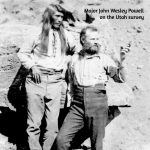

Now, back to the ‘Romance of the Colorado River.’ Do remember that when we talk about ‘romancing’ here, we are not talking about a sappy love story; we are talking about people muscling up to take on a challenge that is beyond or below the mundanity of life. In the last post on this site, we looked at ‘the Colorado River and the Romance of Exploration.’ Dellenbaugh’s Romance of the Colorado River was published in 1903, and covered the adventures of everyone from the early Spanish conquistadores trying to sail up the river from its delta, to the trappers strip-mining the beavers from its upper tributaries, with a final focus on the explorations of John Wesley Powell who first sketch-mapped the unknown area between the upper river and the lower.

Dellenbaugh pulled no punches in describing his sense of the river and the challenge it represented. After noting in his introduction that ‘in every country, the great rivers have presented attractive pathways for interior exploration—gateways for settlement,’ serving as ‘friends and allies’ – he launches into his initial impressions of the Colorado River:

‘By contrast, it is all the more remarkable to meet with one great river which is none of these helpful things, but which, on the contrary, is a veritable dragon, loud in its dangerous lair, defiant, fierce, opposing utility everywhere, refusing absolutely to be bridled by Commerce, perpetuating a wilderness, prohibiting mankind’s encroachments, and in its immediate tide presenting a formidable host of snarling waters whose angry roar, reverberating wildly league after league between giant rock-walls carved through the bowels of the earth, heralds the impossibility of human conquest and smothers hope.’

Opposing utility everywhere? Refusing absolutely to be bridled by Commerce? Heralding the impossibility of human conquest, smothering hope? Could he have said anything more stirring in throwing down the gauntlet to an adolescent civilization?

Dellenbaugh’s Romance does sort of follow the formula of today’s sappy romance novel, but on the grand scale of the romantic adventure: first you establish the object of the protagonist’s ‘dangerous’ love as arrogant or disturbed or otherwise undesirable or unattainable – but therefore… irresistibly attractive. Why are we drawn to such hard cases? Why wouldn’t we leave such an angry and extreme river alone, like countless generations of First Peoples had done, settling riparian along its tributaries and even the mainstream, but just living with the ‘veritable dragon’ as it was, and doing nothing to confront or challenge it? Or to bend it to their perceived needs? But we Euro-Americans are a civilization in which ‘love conquers all’ – or else. Love or its simulacra – lust for wealth, for power, for knowledge, whatever. Come not between a woman and her lust for impossible men – or a civilization and its lust for everything it doesn’t already control.

So it almost seems more destiny than coincidence that when Dellenbaugh wrapped up the ‘Romance of Exploration’ in 1903, that was also the year the U.S. Reclamation Service went to work, following the Reclamation Act of 1902, to reclaim and conserve the river.

We call Theodore Roosevelt ‘the father of American conservation,’ but he did not have the commonly accepted sense of conservation that we have today. Conservation to Roosevelt and his sidekick Gifford Pinchot was the full and efficient development of resources otherwise wasted. Freshwater running off to the ocean in an unmanageable spring flood was a prime example of profligate ‘waste’; they took it on through a Reclamation Service charged with working with farm communities, to develop irrigation systems to get water out of the rampant river and on to the dry land, thus conserving for human use both the land and water, each ‘useless’ until combined with the other.

The Reclamation Service was created as a division of the U.S. Geological Survey, which was still a bulwark of John Wesley Powell’s disciplined science in the otherwise freewheeling Interior Department, aka General Land Office, charged primarily with privatizing the public lands through the Homestead Act and other laws. From the start, the Reclamation Service was filled with idealistic young engineers infused with the spirit of Rooseveltian conservation – the kind of idealism that could gradually transmogrify into the unconscious arrogance of those who Know They Are Doing Good and are therefore Always Right.

Their idealism is reflected in an article written in 1918 by C.J. Blanchard of the U.S. Reclamation Service, for The Mentor, an educational publication:

A vein of romance runs through every form of human endeavor…. In the desert romance finds its chief essentials in adventure, courage, daring and self-sacrifice. For more than half a century man has been writing a romance of compelling interest upon the face of the dusty earth. Irrigation, with Midas’ touch, has changed the desert’s frown to smiling vistas of verdure.

In a section titled ‘The Romance of Reclamation,’ Blanchard described the reclamation engineers as men not concerned about ‘large emoluments, for government salaries are notoriuously meager’; instead, ‘as they toiled in the fastness of mountains, an abysmal canyons or far out in the voiceless desert, through the blazing heat of the Southwest or the fierce blizzards of the northern plains, this thought was uppermost, “By this work we shall make the desert bloom.”’

But the reclamation engineers quickly found working at the farm end of irrigation systems drawing water from the wildly varying flows of the Colorado River frustrating at best, impossible at worst. And they were engineers, not scientists – engineers with a brave new world of technology unfolding; fellow engineers were building the Panama Canal (1904-1914) using steam trains and steam shovels that could move more dirt in an hour than a hundred farmers with shovels could move in a day. Scientists just figure out how the world works; engineers figure out how to make it work better. (or so they hope).

So within their first half-decade the Reclamation Service engineers were drawn toward larger projects that, in effect, would ‘correct’ the inefficiency and maddening variability of the river: the Roosevelt Dam up in the Salt River canyons storing the spring flood for release to irrigators throughout the whole growing season; a concrete weir dam all the way across the lower Colorado River to keep the late summer flows up to the headgate of the Laguna Irrigation Project near Yuma; a five-mile tunnel from the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River to the water-short (or over-developed) Uncompahgre Valley – all three projects begun in 1905-6.

Evolving concrete technology, and the evolving internal combustion engine made them dream of even larger projects, addressing all the natural challenges posed by Dellenbaugh’s ‘veritable dragon.’ In 1907 the Reclamation Service separated from the U.S. Geological Survey and became an independent bureau in the Department of Interior. This separation was more than just a name change; they also began to work independently of John Wesley Powell’s scientific rigor practiced in the Geological Survey.

This became a background issue when the seven states of the Colorado River Basin gathered in 1922 to try to work out an equitable division of the river among themselves. Knowledge of the actual flow of the river was sketchy. Rough measures of the flow at a Yuma gauge only went back to the mid-1890s, and gave an average in the wild annual fluctuations of just under 18 million acre-feet (maf). But a Geological Survey scientist, E. C. LaRue, had studied tree rings and other evidence, and argued that the river was just in a very wet spell, that the longer-term average flow of the river was probably well under 15 maf, maybe as low as 10-12 maf (what it appears to be today). He also cautioned that extensive storage in desert reservoirs would exact a large toll in reservoir evaporation; there would be more water available for use, but the tradeoff would be less water overall.

LaRue – John Wesley Powell’s kind of scientist – offered to consult with the Compact Commission; but nobody really wanted to hear what he was known for saying, and his offer was ignored by Chairman Herbert Hoover (an engineer). But a constant advisory presence at the compact planning meetings was Reclamation Commissioner Arthur Powell Davis, another engineer and an active participant in discussion leading to the commission accepting the Bureau figures, and deciding that a ‘temporary equitable division’ of 15 maf between an upper and lower basin was a reasonably conservative division, leaving enough uncommitted water for ‘those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information, [to] make a further division of the river.’

Current water mavens Eric Kuhn and John Fleck wrote a well-researched book, Science Be Dammed, detailing this decision to ignore solid USGS science in drafting the compact. A more mythic summary of what happened probably lies in desert poet Mary Austin’s recollection of a legend about the Hassayampa River, a Colorado River tributary; if anyone drinks its water, according to the legend, they will ‘no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance.’ Whatever was in the Hassayampa’s water may have infiltrated the entire Colorado River in the 20th century.

Basically, the Bureau of Reclamation, with all the emerging technology and its vision of ‘making the desert bloom,’ was itching to take on the ‘veritable dragon.’ The ‘Romance of Exploration’ had uncovered a rampaging river whose waters were needed for American advancement; the ‘Romance of Conquest’ was the obvious next step, and science just based on the ‘naked facts’ no longer seemed to dictate the limits of the possible. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. That may not have been so baldly stated until 2004, but it was the driving theme of the 20th century – first in America, then globally.

The Romance of Conquest began with the three 1905-6 projects, but shifted into high gear with the Boulder Canyon Project, created by Congress in 1929 following ratification of the Colorado River Compact – almost simultaneously with the onset of the Great Depression. The Project became practically the nation’s only bright light in the early 1930s, and became a template for much of Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal.’

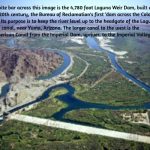

The centerpiece of the Boulder Canyon Project was Hoover Dam, the largest dam project ever undertaken anywhere, capable of storing almost two years of the river’s flow, and as it released water on demand from the ‘desert bloomers’ downstream, it would generate enough electricity to handle most of the Southwest’s power demand at that time. But while the big dam was being built, the Bureau was also building the Imperial Weir Dam 180 miles downstream, to diverting more than three million acre-feet of water into the All-American Canal for an 80-mile trip to the Imperial Valley where crops could be grown year round. And between those two huge works, the Bureau was also overseeing construction of Parker Dam (not officially part of the Boulder Canyon Project) to pool up water for a 250-mile aqueduct a Metropolitan Water District was building to carry domestic water to California’s burgeoning south coast cities.

All of that was completed by 1941 – a massive coordinated regional development: food, water and power for cities that quickly became an industrial force in the winning of World War II. And it was all done on budget, and on time, organized by an agency created only forty years earlier to help small new farming communities build local irrigation systems.

And I’m going to pause there, at the moment of the Bureau’s triumph, and pick up the rest of the story of the Romance of Conquest in the next post here. Stay tuned.

***