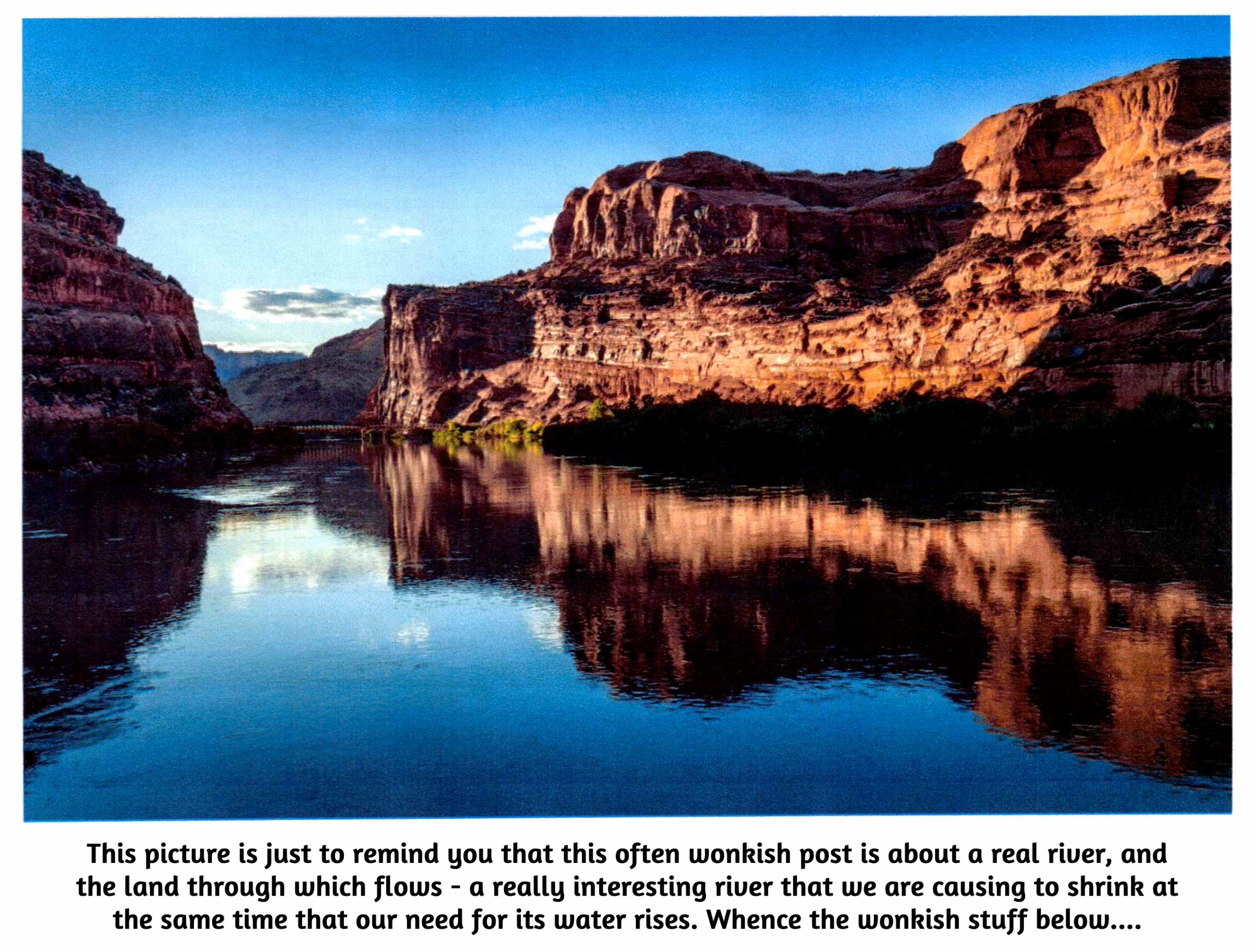

Hard times in the Colorado River region. A near-average snowpack dissipated into an inflow into Powell Reservoir of only 40 percent of average; dry soils in the headwaters and high deserts, and increased evaporation and plant transpiration in a warming world are taking big tolls. And the negotiators for the seven Basin states, trying to work out a river management plan to replace the failing current management strategies, with the 30 Indian nations and Mexico looking over their shoulders, are continuing to… negotiate. Trump’s Interior Department officials have given then until November to negotiate a draft plan for beyond 2026.

Meanwhile the Bureau of Reclamation has issued its annual 24-month projection, and it has no good news. Its worst case scenario – the one everyone looks at – suggests that, barring a huge winter this year, Powell Reservoir might drop to the elevation at which it can no longer produce hydropower by late fall 2026 – at which point it cannot even make large deliveries downstream, because all the water would then have to go through four antique tubes never meant to carry that much water 24/7. This could undermine the best-laid plans of the negotiators, should they achieve a plan, with no ability to move sufficient water past Glen Canyon Dam until the reservoir filled back up to the power level. No plans have been announced for creating a Glen Canyon Dam bypass.

All the news dribbling out of the negotiations indicate that the negotiators persist in carrying forward the Colorado River Compact’s division of the river into Upper and Lower Basins. Do they not see that this is no longer necessary, or even desirable – nothing but a cause of conflict and contention?

When representatives from the seven Colorado River Basin states gathered in Washington in January 1922, six of the states knew what they wanted: they wanted a seven-way division of the consumptive use of the river’s waters that would transcend on the interstate level the appropriation doctrine all seven states adhered to intrastate.

They wanted this because southern California, the seventh state, was growing so fast, and already using so much of the river’s water, that the other six knew they would be losers in a seven-state horse race to appropriate the river’s water. The representatives all accepted the first-come first-served appropriation law as holy writ within their states, but saw its limits when looking at the whole river and the regional challenge of uneven development.

California sat down with the other six states because at that point, the other six states held a big card: California needed a interstate river to control floods and ‘rationalize’ the flow and distribution of the river’s water, rather than watching an uncontrolled flood of snowmelt ‘waste’ most of the water to the ocean. And California knew that Congress would provide for that big dam only if all seven states were sure they would have a share of the water, once the river was controlled. So California had to participate in setting long-term limits on itself in order to get what it needed in the short term.

But after several days of trying to work out that seven-way division, the compact negotiators gave up in frustration. Each negotiator had come with estimates of his state’s future water needs based on potentially arable land, mining-generated industry, possible urban development. Not really knowing what the future would bring did not dim their estimates at the turn of the 20th century, with the imperial impetus to ‘create our own reality’ just kicking into high gear. But by the time the seven negotiators had laid out their states’ envisioned water needs, the basin-wide total was half again even the Bureau of Reclamation’s rosiest estimates of Colorado River flows. And no one wanted to cut their estimates, go home to tell their governor and legislators he’d had to diminish the state’s envisioned future by a quarter or so.

Several of the frustrated negotiators thought they should abandon the whole idea of an interstate compact, but the federal representative and chairman, Herbert Hoover – himself an engineer eager to see the big dam built – persuaded them to stay with the idea for the rest of the year. They convened for some hearings around the west in the summer, and had a tour of the proposed big dam sites. But then Hoover and Colorado’s representative to the commission, Delph Carpenter, began circulating the idea of a two-basin division to break the impasse over the seven-way division, and Hoover was able to convene a November charrette to work until a compact was done.

Toward the end of an eleven-day marathon at a resort near Santa Fe, with 18 transcribed sessions and who knows how many informal barroom and hotel room caucuses, Chairman Hoover summarized their situation:

We finally reached, in effect, this general conclusion as to the form of the compact, and that was that none of the figures and data in our possession, or within the possibility of possession at this time were sufficient upon which we could make an equitable division of the waters of the Colorado River [in perpetuity]…. [W]e make now, for lack of a better word, a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river. (Text from the 12th of 18 transcribed November meetings, boldface added)

That was the Colorado River Compact as seen in process by the commission chairman: ‘a temporary equitable division’ to be refined and finished when ‘a greater fund of information’ about both the river’s flows and the flow of the future was known. No one – with the probable exception of Delph Carpenter – was very happy with the Compact the commissioners took home to their states. Arizona refused to ratify it, and it took several years to get it through the other six state legislatures. But the U.S. Congress was actually somewhat eager to develop the river, making its desert lands available for development, and decided that six of the seven states on board was good enough. The Boulder Canyon Project Act was passed in 1928, and Hoover – then President – was able to launch construction of not just the huge Hoover Dam, but Parker Dam as the holding bay for the Metropolitan Water District’s 250-mile aqueduct, and the Imperial Dam and All-American Canal to carry water to the Imperial and Coachella Valleys – a major regional development that really set a course for the 20th century.

Enabling that, and what followed over the next four or five decades, did achieve the Compact goal to ‘secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin,’ probably the major goal stated in its preamble (Article I) for most of those involved. But a century later we can say pretty definitely that its ‘temporary equitable division’ (still apparently regarded as permanent), has not achieved most of the other goals listed in the preamble. It did not ‘provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters,’ either in the division between Basins explicit in Article III(a) nor in the relationship between the two Basins stated in Article III(d); it obviously did not ‘promote interstate comity’; and the two-basin division did not ‘remove causes of present and future controversies.’ If anything, the Compact created controversies with badly written sections like Article III(c) on the Mexican obligation, and Article III(d) on interbasin ‘obligations.’ (If you would like to review the Compact, you can find it here.)

More to the point – it is possible now to achieve what the 1922 commissioners originally wanted: an equitable seven-way division of the use of the river with a share for Mexico, which renders the two-basin ‘temporary division’ irrelevant and burdensome.

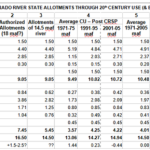

The seven-way division has been effected, not through interstate negotiation but through the ‘continued development of the river’; today, the seven states and Mexico all know, practically to the acre-foot, what has evolved as their share of the river as we have known it – the 14.6 million acre-foot average flow of the development period, the 1930s through the 1990s.

Allotments for the three Lower Basin states were set by the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1929 as acre-foot portions of the Compact allotment of 7.5 maf, and confirmed by the Supreme Court in its 1963-4 Arizona v. California decision. Mexico received its share, 1.5 maf, in a 1944 treaty negotiated through the U.S. State Department. And the four Upper Basin states negotiated a compact for their share of the river in 1948 – by then known to be a variable quantity, usually less than the Compact’s allotment of 7.5 maf, so they divided their fluctuating share by percentages.

The ‘federal reserved rights’ of the Basin’s 30 Indian nations – barely given a ‘placeholder’ in the Compact – have been shoehorned in as state responsibilities through the 1952 ‘McCarran Amendment’ to a resource bill; this says that all federal reserved water rights, for all public lands as well as the Indian reservations, have to be adjudicated in the state water courts. The ‘equity’ of this is questionable; some states have only a few Indian nations; Arizona has 22 of them. Most of the Indian nations that have not already achieved some water rights are working on ‘settlements’ out of court, negotiating with those who have been using water for which the Indians had a prior claim (dating from the creation of their reservation) for water and money with which to develop the water they can get. The federal government puts up much of the money for the development of Indian water rights; there is still a long way to go in correcting this long-standing dereliction and shame, but there has been more activity in the past couple decades than in the previous century.

The point being – nearly everyone knows with some accuracy how much water they have had to use from the Colorado River – in the 20th century. Hardly anyone is happy with the resulting numbers, but we also all know that this is all the water there is – or was, in the 20th century. The river has been divided among the states and nations, de facto, if not yet de jure.

The alarming draw-down of the river’s major reservoirs in the early 21st century to date has been only partially caused by the ‘drought’ and permanent climate-related aridification. The bulk of the draw-down has been a ‘structural deficit’ stemming from the Lower Basin states’ blithe refusal to incorporate their ‘system losses’ – evaporation and transpiration, riparian losses, etc – and their portion of the Mexican share into their allotments, preferring to let the amenable Bureau release them as ‘surplus’ from Powell and Mead storage – a surplus that has not existed since the Central Arizona Project began to come on line after 1985, along with increased Upper Basin uses (still well below its ‘Compact allotment’). The Compact failed to include system loss provisions – probably around 12-14 percent of the water that flows from the headwaters snowpack.

The good news there is that, in the planning for river management beyond 2026, the Lower Basin states have agreed to absorb the ‘structural deficit’ and their share of the Mexican obligation into their river shares. The Upper Basin users have already absorbed their system losses by the time the Bureau moves Lower Basin water out of Powell.

It is not rocket science to lay out the seven-states-plus-Mexico division of the waters in a chart, a feat impossible in 1922, but largely accomplished de facto by the Compact’s century mark – a chart without any reference to the ‘temporary equitable division’ into two basins. If we were to eliminate the two-basin division form our future management plans, we would unload quite a lot of unnecessary baggage. We would be much closer to thinking of the Colorado again as one river, with one set of challenges for everyone, rather than this ‘Cold War’ between Upper and Lower.

The big challenge comes in trying to fit that division of the 14.6 maf river of 1930-2000 into the river we have today – ~12.5 maf, and dropping incrementally but steadily.

If we lived in a fair, just and moral universe, resolution of management guidelines for the future of the one river would just be a matter of applying basic high school math: if a state’s allotment (including a proportionate share of system losses) of a 14.6 maf river is X maf, what will be that state’s new allotment if the river’s volume drops to 12.5 maf? Or to 11.5 maf by 2050? Easy: you just convert the state’s allotment to a percentage of the 14.6 maf river, and multiply those percentages by 12.5 maf, or whatever the flow has dropped too. Do that for all users and, presto, there’s everyone’s new 21st-century allotment, learn how to live with it –

Wups. Uh-oh. One can already hear the ‘harrumphing’ firing up in the Imperial Valley: what about our senior water rights?! If you say we have to take the same cuts as everyone else, we’ll see you in court!

The Interior Department’s current acting assistant secretary for water and science, Scott Cameron, actually spoke to that eventuality or probability in a meeting of water mavens in Arizona: ‘Having senior water rights is a wonderful thing, but having senior water rights does not give you a free pass to ignore what’s happening in the greater community.’

What’s happening in the greater community is diminishing flows for everyone due to a warming, drying climate that is everyone’s and no one’s fault – a problem of a different order of magnitude from the issues the senior-junior appropriation doctrine developed to resolve. If Asst. Secretary Cameron’s perception (unusually perceptive from an official in the Trump administration) were to prevail as federal policy, it might facilitate a serious discussion in the arid West about how far and how high a body of law should be applied, that originated for working out squabbles between neighbors – with ‘first-come first-served’ the one-size-fits-all resolution. A resolution that is usually transcended locally in dry times with ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ to share the pain between neighbors who have also become friends.

The westerners who convened for the 1922 compact commission wanted to suspend at the interstate level the appropriation doctrine they all adhered at home, for good reasons involving the uneven pace of regional development. We are now confronting a reduced volume of water for everyone, caused by a changing climate that is no one’s and everyone’s fault. Is this not a problem on a scale with the problem that convened a Compact commission a century ago to suspend – or more accurately, maybe, transcend – the appropriation doctrine at the interstate level?

Well – we keep getting news every day about the fairness, justice and morality of our small sector of the universe. Pray for rain; it’s more likely.

Excellent installment, George. Thought provoking, too, especially in these “DJT’s way or else” times in DC. The last thing any of the 7 states and Mexico should want is for the White House to design and then order the implementation of a “new Compact”.

The White House would probably suggest we just turn on the Mississippi faucet.

Okay, I am just simply going to print this for my climate change list because this is real world in historical context. EXACTLY what is missing in almost everything in this cursed nation. But we shall keep trying. Thank you my friend.

Thanks as always George. Unfortunately, calculating allocation on a percentage basis is just too simple, too fair and too logical, so we’re all sitting around, holding our collective breath for a presidential proclamation to drop. ‘Heaven’ help us!

Pray for rain, Hap.

Okay, now I know everything! First, I want to mention the wonderful photo and cutline at the top. Terrific! As for a “draft plan” being available by November? Well, a wet day in Kayenta is more likely. The lay reader re: this whole river problem reads (mol) “without a killer winter, Powell is in danger of not being able to make power…” and thinks, that there is a long shot, killer winter. More likely, Powell disappears into Dead Pool and what then? With all this study does not automatically follow wisdom, as evidenced by the refusal to acknowledge the part in the original compact about “temporary until those with more information…” choosing instead to hang on for dear life to what they have long had, even though what they have long had no longer exists. We often wonder why so many vote against their own best interests. Here we have one more example, persisting in Upper and Lower Basin misdirection is sure to lead to those bypass tubes at the bottom of Powell. This one is loud and clear, George, another great report to help us realize the tremulous state of Colorado River affairs. Thanks.