Way too much is happening in the world today, beyond the Colorado River. An Armageddon is shaping up in the mideastern Cradle of Too Many Civilizations that makes Colorado River problems look like sandlot scuffles; we’re in a long slog toward an election in the Untied (sic) States that would not even be close in a rational nation-state but somehow, ominously, is close here; a so-called Cold War is heating up again between competing military-industrial complexes that are again dragging us to the brink of unimaginable disaster. As if the changing climate were not already enough unimaginability. Much about our future is unimaginable today.

Those apocalyptic challenges make a focus on my favorite river almost feel like a guilty diversion, but there’s a lot of fundamental roiling and boiling going on along and around the Colorado River too – a lot of it dependent on intelligent adaptation to unimaginables like the supercharged climate. Will the Upper and Lower River Basins reconvene – together – in time to get serious about planning for the Post-2026 era? Does the expiration of the beat-up and bandaged Interim Guidelines also mean the expiration of the dysfunctional Colorado River Compact and its two-basin wet dream for a pluvial river that no longer exists? Will the Bureau engineers have to breach Glen Canyon Dam to get water past it, once the bypass tubes collapse, raising dead pool to a third of the reservoir capacity? And – oh yeah, will the seven states actually incorporate the 30 First People tribes into actively helping plan our water-based future?

This post will follow through on that last question. In my last post, I was trying to provide some historical and cultural context for a letter sixteen of the Basin’s First People tribes sent to Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton in late April, reiterating emphatically their strong desire to become a full partner in the future planning and use of the Colorado River:

We, the undersigned tribal leaders, believe it is now time to more specifically explain the Basin Tribes’ key principles that must be adhered to if the United States, as our trustee, and the Basin States expect our support of any proposed or preferred alternative for the Post-2026 Guidelines.(Emphasis added)

That’s a fairly emphatic government-to-government demand from people historically confined to the role of powerless petitioners, signers of ‘in perpetuity’ treaties that often barely lasted a decade before their trustees broke them. What can the First People do if, as usual, that demand is ignored, and their federal trustee and the seven states continue to not be unduly concerned about having the support of the tribes in what they do (including what they do to the tribes)?

I actually think the First People could probably do quite a bit at this point, not with bows and arrows, but by applying what they’ve learned from civilized America and taking their self-appointed trustee, the U.S. government, to court – not just the warpedy judicial system, but also the ‘world court’ of mediated public opinion. For the last third of the 20th century, since the American Indian Movement, with Western Civilization beginning to show cracks and peeling facades, public awareness of, interest in, and concern about the First People and their cultures has increased; thay have developed a voice that is heard.

The shape of the future may have been set this year, at roughly the same time the 16-nation letter went to the Bureau: the Upper Colorado River Commissioners held their first formal meeting with representatives of the six tribes in the Upper Basin; both parties have committed to regular meetings in the future.

What will they talk about? Probably they will talk first about the three ‘key principles’ in the letter to the Bureau: first, that their alleged trustees ‘take actions to actively protect Tribal water rights’ as the permanent cuts in use begin for the post-2026 epoch. Second, that the Tribes themselves finally be empowered ‘to determine how and when to use their water rights by adopting and supporting a portfolio of flexible tools’ for the Tribes. And third, that the government and states ‘provide for a permanent, formalized structure for Tribal participation in implementing Post-2026 Guidelines, and in any future Colorado River policy and governance.’

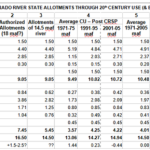

A first question in contemplating these principles might be – what are the ‘Tribal water rights’? They were first asserted by the U.S. Supreme Court, in the 1908 Winters v. United States decision, that granted tribes confined to reservations enough water to achieve the reservation purpose (‘civilizing’ the First People). A number of the tribes have actually acquired substantial portfolios, mostly dating to the creation of their reservation. A compilation from two reputable studies indicates that 23 of the 30 First People tribes have paper rights to 4,379,375 acre-feet of water – a full third of the current annual flow of the river. Because this information might sound a little unbelievable, these are the two documents that reveal it: first, a joint study by the Bureau of Reclamation and a ‘Ten Tribes Partnership’; the second, a Congressional Research Service study on ‘Indian Water Rights Settlements.’

First People water rights, you might recall from an earlier post, are obtained in two ways – either of which typically takes years, even decades, to execute: one is to take the federal or state government to court, suing for their rights. Their rights were ‘federal reserved rights,’ but they had to be adjudicated through the legal processes of the state they were in.

The other way was for the First People to engage in direct negotiations with the Euro-American entities – mostly irrigators and private and public domestic users – who have been legally using their ‘federal reserved’ water. The federal government rides shotgun with the tribes on such negotiations, putting on the table the amount of money Interior lawyers figured it would cost the government to go to court for the First People. The farmers and municipalities and others using the water are willing to negotiate as an alternative to going to court in what might ultimately be an expensive losing case.

These negotiated ‘settlements’ have become the preferred method for both the tribes and the governments, offering a lot more flexibility in ‘horse trading’ than the courts allow. Eighteen of the First People tribes in the Basin have obtained rights through negotiated settlements, five through the courts; the remaining seven First People nations with no decreed rights will probably follow the settlement course. If you are interested in browsing a copy of a settlement agreement, this links to the one for the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community – the People whose Great Seal is the maze illuminating the last post here. Just a quick look at the table of contents will show why the maze is an appropriate symbol for these still-evolving relationships.

But this tally of 4.4 million acre-feet (maf) of water rights for 23 of the 30 Colorado River Basin tribes is, as noted, ‘paper water’ – the right to use the water. To actually put the water to use – turn it into ‘wet water’ serving some purpose – requires expensive infrastructure, especially in the desert. On average, the individual First People tribes have only turned, on average, a fourth of their decreed paper water into wet water, according to the 2018 study by the Bureau and Ten Tribe Partnership. The rest of their decreed water is being used (free) by others – mostly farmers and municipalities, all with legal rights.

In trying to address this situation, the First People tribes are well aware that the Colorado River is already over-appropriated almost everywhere, and that their federal reserved water has been used productively for more than a century by other users with legal water rights that would become ‘junior’ if contested by the tribe’s senior reserved rights. But forcing those longtime users to give up the Indian water would just push them to pumping more groundwater, still (unbelievably) unrestricted in most of Arizona. The tribes specifically asked in their letter to the Bureau that the government ‘facilitate the creation of compensated forbearance agreements that enable Basin Tribes to benefit from their water rights in a manner that avoids increasing cumulative consumptive demand.’ (Emphasis added) In other words – don’t make us make the situation worse for everyone else in making it better for us.

The logical, common sense action would be to allow the First People to charge current users of their water to continue using it and not be forced to the expense of pumping groundwater, with the First People using the proceeds to improve their own water infrastructure, making their water go further. This logical, common sense action, however, is illegal under the antiquated 1834 ‘Indian Non-Intercourse Act,’ forbidding First People nations to lease or sell their reservation land and resources without Congressional approval.

One First People community right on the Colorado River has gone to Congress to seek that approval, and in 2022 Congress passed the ‘Colorado River Indian Tribes Water Resiliency Act,’ which, despite the omnibus sound of the title, only permitted the First People community on one reservation to address the opportunity of ‘compensated forebearance agreements.’

The ‘Colorado River Indian Tribes’ (CRIT) reservation was created in 1865 for the groups of the Chemehuevi and Mojave tribes – at their request. Well into their own transition from hunter-foragers to farming, they were concerned that their traditional lands were being overrun by the white tsunami unleased by the gold and silver ‘rushes,’ and they were willing to sacrifice their upland hunting grounds if they could be have their floodplain farmland along the river. Indian Affairs agent Charles Poston made that happen for them, generating a relatively large reservation, 353 square miles in Arizona and 67 square miles in California, and 113 miles of Colorado River access. A reservation town is named for Poston, an agent who treated them like humans.

After that unusual 19th century beginning, the People experienced the usual traumas imposed by American Indian policy, combining general neglect with efforts at forced assimilation – a combo that the tribes barely survived.There were also unintentional challenges: their farming technique was to plant their ‘three sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – in the rich mud as the annual spring flood of snowmelt receded, with no additional irrigation required. That was disrupted when Hoover Dam was completed, ending the floods. They petitioned Indian Affairs for assistance in setting up an irrigation system with marginal results. And the Indian Affairs Office also doubled the number of First People tribes in the CRIT community, bringing several bands of Hopis and Navajos onto the reservation, an unwelcome addition crowding an already inadequate irrigation infrastructure.

But then, as the nation descended into World War II, the four-tribe community got way more crowded: the reservation became host to the largest internment camp for American citizens of Japanese descent relocated from the West Coast – 17,000 people by 1945. But this was followed by a most unexpected but welcome development. In the early years of World War II, with all the nation’s industrial resources diverted to war production and most of the traditional workforce in the military, the Bureau of Reclamation found enough concrete and steel and workers to build the Headgate Rock Diversion Dam across the Colorado River, to divert irrigation water onto – an Indian reservation? And internment camp?

I searched the Bureau’s websites in vain for information on this project, and found nothing – from an organization that has excellent histories for nearly all of the projects it has built; they don’t even list Headgate Rock as a project – perhaps because the Bureau of Indian Affairs manages it. But accounts of the internment camp note that the Japanese Americans worked with the CRIT First People in developing the irrigation works, and all who survived the experience did so in part because of the extensive new irrigation system. Typically for the internment camps for Japanese Americans, by the time they were released in 1945, the camp itself had become a more livable place with gardens and trees; after the war, the Hopi and Navajo people were moved into some of the housing.

The CRIT then received a big break in 1964. In the decree resolving (sort of) the ongoing feud between Arizona and California, the U.S. Supreme Court included water rights for all the First People tribes and the CRIT multi-tribe community living along the Colorado River, rights quantified in the 1970s; CRIT, being the largest Colorado mainstem reservation with the most existing water development, got consumptive use decrees for 719,000 acre-feet in Arizona and California, the largest decree for any single entity in Arizona. They have managed to put to use about half of their decree, and want to lease some of the rest to those already using their water, which is why they petitioned Congress recently for the 2022 act to do that.

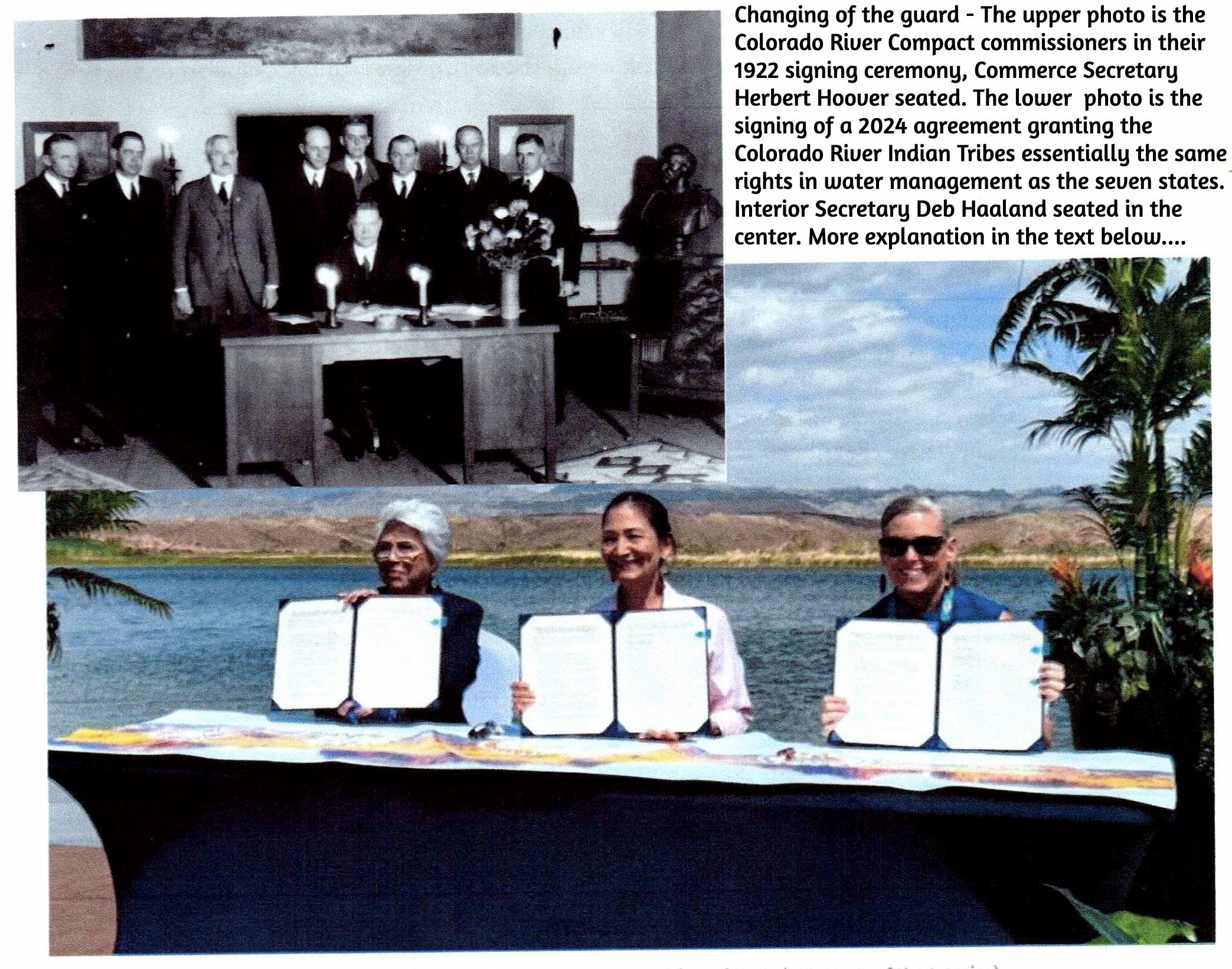

And that brings us to the photo at the beginning of this post, which is the signing of the agreement between the CRIT People and the Arizona and federal governments. Any reader with a sense of history will see immediately what is unusual about this picture: the signers are all women – and two of them are of the First People: on the viewer’s left, Amelia Flores, Chair of the CRIT community; in the center, Deb Haaland, U.S. Interior Secretary (Laguna Pueblo); and on the right, Arizona governor Katie Hobbs, who had the gumption to shut down part of Arizona’s growth juggernaut, the ‘Hassayampa romantics’ who could not verify a hundred-year water supply for their developments.

Everyone in the Colorado River region today talks about a need to be ‘thinking outside the box.’ That picture seems to me to be ‘outside the box’ – as does the meeting between the Upper Colorado River Commission and the six First People tribes in the upper basin states. Congress might follow that by repealing the 1834 Indian Non-intercourse Act and generalizing the 2022 CRIT Water Resiliency Act with a uniform policy for all First People reservations – although uniformity has never been an international feature of the Indian nations.

Of course, that will all change if Trump wins the presidency: he promises to take us back to the past to avoid the unimaginable future.

But that note is no way to end this; I’ll instead give the last word to the ‘Poston (Arizona) Community Alliance’ on the CRIT reservation, committed to carrying forward ‘Poston’s unique multicultural history, involving Japanese Americans and Native Americans.’ In 1992, the 50th anniversary of the internment camp, the Alliance raised a 30-foot monument with this quotation:

This memorial is dedicated to all those men, women, and children who suffered countless hardships and indignities at the hands of a nation misguided by hysteria, racial prejudice, and fear. May it serve as a constant reminder of our past so that Americans in the future will never again be denied their constitutional rights, and may the remembrance of that experience serve to advance the evolution of the human spirit.”

That’s the way to make America great – finally.

Wow! Had no idea about that internment camp. Thanks again, George

Focusing what passes for local is a way of maintaining sanity and I commend your for that. The fact that the Winters was ignored for over 100 years explains why you found NOTHING on the Reclamation website about The Headgate project or camp. Reclamation just ignores anything unpleasant and the excellent histories you talk about are NOT always backed by facts. I read more that 30 years of Reclamation Annual reports that included, among other, yield per acre on various projects. About 5 years in I realized the numbers in many projects were identical, year after year. Many if not most projects were politically motivated and that’s why the records are so often hidden. I am cynical on this.

However, your last two paragraphs provide a ray of hope. For that I thank you

It’s certainly a convoluted story, George, but I love that last part. We could do a lot worse than pay attention to, and genuinely try to follow, that monument’s inscription.