In my last post, I was questioning the process of allowing the privatization of the commons through individual appropriations – in our specific instance here, privatization of the ‘water commons,’ but also of the land, and all of its living systems and the raw resources that must feed, water, shelter not just us but all life on the planet. Every living thing that requires food, water, air or virtually anything at all ‘appropriates it from the commons,’ and probably in the strictest sense we all ‘create a property’ in the apples we pick to eat, the water we dip out of the stream to drink, the oxygen in the air we suck into our lungs. But we have not always gone on to claim personal ownership of the tree that produced the apple, or the land the tree grows on, the stream that waters the tree. That is a relatively recent invention of modern cultures – the agricultural and the … Read More

Romancing the River: Is Appropriation from the Commons ‘Natural’?

Though the water running in the fountain be every one’s, yet who can doubt, but that in the pitcher is his only who drew it out? His labour hath taken it out of the hands of nature, where it was common, and belonged equally to all her children, and hath thereby appropriated it to himself. – John Locke, from Second Treatise of Government Decision-making about the parlous Colorado River situation is currently somewhat hung up in a surly debate about the absolute ‘rule of law’ versus the kind of equity and fairness most laws are created to further. Six of the seven Colorado River states are willing to take proportional shares of the pain for some major cuts in water usage that must happen for the river system to remain functional. But the seventh state, California, insists that the pain be administered strictly according to the foundational law of the river basin, the appropriation law, whereby junior water users bear … Read More

Romancing the River: Meanwhile Back in Central Arizona

There’s a bit of a lull in the multiple conversations up and down the Colorado River Basin, with some positions staked out, while the Bureau of Reclamation initiates an ‘emergency environmental impact statement’ to ascertain, supposedly by late summer, what resolution it will either accept from the seven Basin states, or impose on the states, to reduce consumptive use throughout the Basin by two million acre-feet or more. All of this is of course being covered in the mainstream media as a ‘water war,’ in their constant efforts to pump any cultural exchange up to a ‘let’s you and him fight’ situation. To call cultural negotiations a ‘war,’ even noisy negotitions among parties with interests at stake, both trivializes the terrible nature of ‘war’ and casts the exchange in an often exaggerated aspect of belligerent violence. If you want to read about a Colorado River water war – fictional of course – pick up a copy of The Water Knife … Read More

Romancing the River: Caliphobia and the Colorado River

‘Caliphobia’ is a cultural germ that infects many Americans everywhere. ‘Caliphobia’ is fear and loathing of the State of California, the state that always seems to be ahead of everyone else in everything, bringing us everything from new entertainments and toys, to new laws on cultural frontiers the rest of us know we ought to be brave enough to embrace ourselves. I’m thinking of things like auto emission standards where the size of the California market brought the automobile industry to heel, with the nation eventually falling in line too. We hate them when they’re right. Californians also occasionally take a big step backward in a deliberate way, and the nation eventually falls in step there too – remember ‘Proposition 13,’ California’s 1978 property tax revolution to protect existing homeowners at the expense of community health, a battle which ultimately generated the national ‘Tea Party’ and the Trumpian ‘I’ve got mine Jack’ culture. We hate them when they’re successfully wrong. … Read More

Romancing the River: Deja Vu….

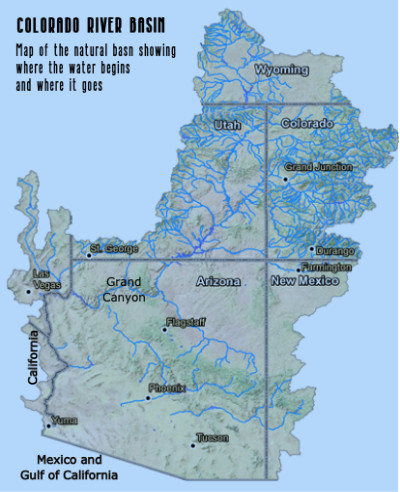

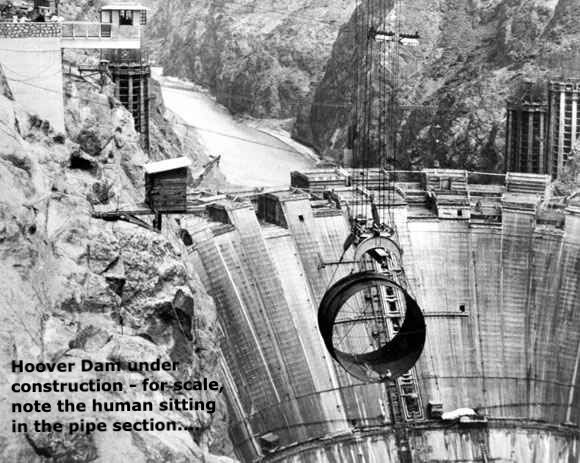

Unless you’ve been living in a media-free cave somewhere, you are probably aware that the Colorado River is again prominent in the news. What’s not really noticed, but ought to be, is the extent to which we find ourselves today almost exactly where we were 101 years ago this winter, with six of the Colorado River states in tension with the seventh state over basically the same topic: the appropriateness of appropriation law as the only legal means for allotting use of the river’s water. The line of conflict today is being drawn over the increasingly depleted state of the two big storage reservoirs on the Colorado River’s mainstream, Mead and Powell Reservoirs. The Bureau of Reclamation, the ever-optimistic manager of the river’s storage and distribution system, has finally acknowledged that its reservoirs are getting uncomfortably close to a ‘dead pool’ situation whereby it would not only be unable to generate electric power, but would even be unable to get … Read More

Romancing the River: Quo Vadimus 2

…the fabled Hassayampa… of whose waters, if any drink, they can no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance. – Mary Austin, ‘Land of Little Rain’ That fabled Hassayampa is in the news these days, down in Arizona. The Hassayampa River does exist, by the way: an intermittent stream that flows off the south slopes of the Colorado Plateau, and down through a desert valley west of the sprawling phenomenon of Phoenix, where it joins the Gila River, which in turn joins the Colorado River down near Yuma and the Mexican border. A new development has been proposed for the lower Hassayampa Valley, catering to those trying to stay out ahead of the sprawl: the Howard Hughes Corporation wants to turn 37,000 acres of Sonoran desert land there, just west of the White Tank Mountains, into a new development, Teravalis, with 100,000 homes for maybe 300,000 people, and 55 million square feet of … Read More

Romancing the River: Quo vadimus?

Enough gallivanting around the Mississippi Basin and its rivers; back to the troubled and troublesome Colorado River, currently experiencing its worst dry spell since around 800 CE. The Colorado Rivers, I should maybe say, since for all practical (human) purposes the river is now managed in a quasi-de jure way as two river basins under the Colorado River Compact and subsequent ‘Law of the River’ actions: an Upper Colorado River and a Lower Colorado River. Previously here, I’ve been exploring the Colorado River Compact at its centennial, in what is certainly the worst year in its century. Here are some things I came up with in that exploration, that I don’t think are getting enough attention in our efforts to search our own souls and the soul of the river in the desert as we try to figure out where we are going from here: 1. The Colorado River Compact is not the ‘foundation of the Law of the River.’ … Read More

Romancing Another River: The Sib-Lea and the Missouri

That’s me in the picture, looking at the Missouri River, which Maryo and I encountered on a meandering journey home to Colorado from Wisconsin. Our meanders took us down through Missouri in search of the story behind a small village named ‘Sibley’ on that river. What we found was another George Sibley, the gentleman in the inset image: an early 19th century George Sibley who – working with the Missouri River and what it ran through – played a significant role in opening up the trans-Mississippi West. I’ve since looked into the life and times of that George Sibley. I’ve learned, among other things, that we are not directly related, but we branch off from a common ancestor: John Sibley, who came to America with an advance party of Puritans in 1629, to ‘make straight in the wilderness the way’ for the 11 ships and 1,000 Puritans John Winthrop led to ‘New England’ in 1630. John Sibley had four sons … Read More

Romancing Another River

This post comes from Wisconsin. I’m taking a break from the Colorado River this week, and writing instead from the banks of the Wisconsin River. We’re in Wisconsin every October because it’s the home state of my partner Maryo. She’s happy enough where we are, in Gunnison near the Colorado River headwaters, but a big piece of her heart will always be in Wisconsin; a month every year in Wisconsin is like a vaccination against terminal homesickness. After sixteen years of this, however, I have come to appreciate and value the month in Wisconsin almost as much as Maryo does. Like Colorado, Wisconsin is a beautiful state, but it is a different beauty. Colorado’s attraction, for me anyway, has always lain in its vastness, its suprahuman scale; it is empty in the way of a promised land, grandly desolate in a way that both challenges and affirms the proud and lonely part of the soul; it makes me think there … Read More

Romancing the River: The Law of the River

“Now we have to come to terms with the fact that there are limits. That’s not the American way to recognize limits.” – Jack Schmidt, Director Center for Colorado River Studies University of Utah For the past several posts, we’ve been exploring the Colorado River Compact, commemorating its centennial this year. Nearly everything I have read about the Colorado River Compact in this centennial year – and it’s getting to be voluminous – speaks of it as the ‘foundation’ of ‘The Law of the River,’ an accumulation of legal and political documents accompanying the development of the Colorado River since the 1922 Compact. I have a problem with calling the Compact the ‘foundation’ of the Law of the River – as though before the Compact was adopted, the River was lawless. That is not true. The real foundation of the Law of the River is the appropriations doctrine that all seven states (or territories) had embraced in the 19th century … Read More